An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

5 min read

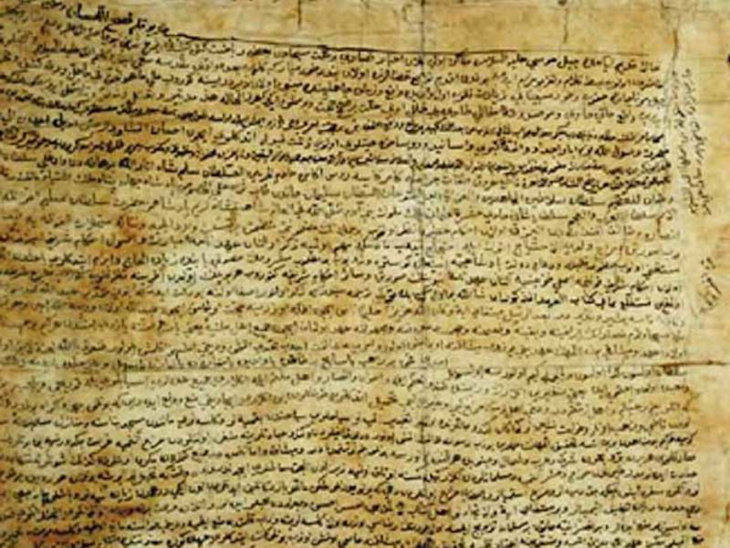

The Constitution of Medina is one of the earliest documents in Islamic history. Some historians view it as a model of a pluralistic society.

The origins of the Jewish roots of the Arabian Peninsula abound in legends. According to oral traditions of the Yemenite Jewish community itself, Jews first wandered from Sinai into the Arabian Peninsula while lost in the desert during the Exodus from Egypt. At a later biblical period, the Book of Kings discusses King Solomon’s trading of gifts with the Queen of Sheba, believed by some to be located in present-day Yemen. Finally, Jews descended to live in Yemen permanently amongst the exiles of the 10 lost tribes around 722 BCE.

Archaeological evidence discovered in the 20th century confirms an ongoing Jewish presence in the Arabian Peninsula since roughly the fourth century and introduces a previously unknown chapter in Arabian Jewish history: the conversion of the ancient “Kingdom of Himyar” to Judaism. The Himyarites ruled pre-modern Yemen for three centuries from their capital of Himyar, close to the dazzling stone city of Sana, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Sana, Yemen

Sana, Yemen

Providing further confirmation for the discovery of a Jewish-Himyarite Kingdom are funerary inscriptions found in the Roman-era Israeli cemetery of Beth She’arim. Evidently, Jews Yemen were brought to the Land of Israel to be buried. While few details are known about “Himyarite Judaism,” and Yemenite Jews are not cited in the Talmud, the presumption that Jews in Yemen had deep cultural connections with the talmudic academies of the Land of Israel and Babylon explains a historical enigma that has challenged scholars for over two centuries.

Since the beginning of the scientific study of Islam in the 19th century, in which a pioneering role was played by the Hungarian-Jewish Rabbi Ignác Goldziher, scholars have sought to explain the following conundrum: how is it possible that Jewish traditions from the Land of Israel and Babylon are found in the Qur’an, a text completed in the year 632 CE in Arabia, when no rabbinic academies are known to have existed anywhere close to the Arabian peninsula?

Rabbi Ignác Goldziher

Rabbi Ignác Goldziher

A startling example of Muhammad’s borrowing of Jewish ideas and motifs is the following Quranic verse that bears a startling example to a rabbinic teaching found in the Mishna: “For that cause We decreed for the Children of Israel that whosoever kills a human being for other than manslaughter or corruption in the earth, it shall be as if he had killed all mankind, and whoso saves the life of one, it shall be as if he had saved the life of all mankind” (Qur’an 5:32).

The Quranic verse is so similar to the third-century Mishnaic text that it almost appears cut and pasted.

The above Quranic verse is so similar to the third-century Mishnaic text that it almost appears cut and pasted: “Whoever destroys a single life is considered to have destroyed the whole world, and whoever saves a single life is considered to have saved the whole world” (Sanhedrin 4:5). Comparing these two verses, scholars have concluded that Jewish oral traditions migrated from the Land of Israel and Babylonia to Yemen, and via the Yemenite Jewish community to Islam.

Indeed, the early biographies of the Muhammad’s life are replete with anecdotes of his interactions with Jewish leaders in both the cities that form the backdrop of his life and career. There, in Mecca and Medina (then called “Yathrib”), existed the Jewish tribes known as Nadīr and Qurayza respectively. According to the Islamic tradition, the first person to greet Muhammad upon his arrival to Medina from Mecca was a Jew! The Jews that Muhammad met in Medina were instrumental in shaping the text of the Qur’an, which includes lengthy passages on biblical characters such as Noah, Jonah, and Abraham. Indeed, the most cited person in the Qur’an is not Muhammad himself; it is the Jewish prophet Moses (136 times).

While the latter part of Muhammad’s life witnessed conflict between the early followers of Islam and the established Jewish tribes of Arabia, it is worthwhile to dwell on the lessons of the “Constitution of Medina,” the very first legal document in Islamic history that was formed in the first year of Muhammad’s arrival in Medina (623 AD). While no copy of the Constitution of Medina survived from the seventh century until the present day, it is quoted in multiple sources allowing academics to partially reconstruct its text.

The Constitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina

The context of the Constitution of Medina is that Muhammad, upon arriving in Medina, sought to make treaties with the local tribes, including the Jews, in order to maintain peaceful relationships. By allowing his followers (the early Muslims) and those already present in Medina to co-exist, Muhammad was creating what legal scholar Ali Khan calls the “first Islamic state.”

The Constitution begins with a prayer and continues (a full version can be read here):

“In the name of God, the Beneficent and the Merciful: This is a prescript of Muhammad… to operate between the faithful and the followers of Islam from among the Quraish and the people of Madina and those who may be under them, may join them and take part in wars in their company. They shall constitute a separate political unit (Ummat) as distinguished from all the people (of the world).”

While far from the norms of western democracies, the Constitution of Medina is a good working model of peaceful relations between Muslims and non-Muslims that existed in the early period of Islam. It continues to inspire those who wish to see an end to religious intolerance towards religious minorities in the Islamic world.