An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

9 min read

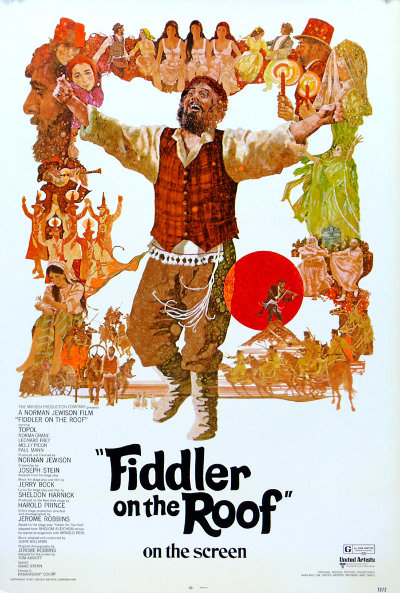

With the passing of Chaim Topol, we remember the film that catapulted him to fame.

Israeli actor Chaim Topol, famous for playing Tevye on stage and in the film version of “Fiddler on the Roof,” died Thursday, March 9, 2023 at the age of 87 after battling Alzheimer’s.

Growing up, a surprisingly large amount of what I knew about Judaism came from my favorite movie, Fiddler on the Roof. The musical captures much of the joy of Jewish life and traditions, and gets some key points wrong as well.

Here are a few things Fiddler gets right, and two things it gets wrong.

The 1964 Broadway musical was based on stories written by the famous Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem. His series of short stories about “Tevye the Dairyman” introduced readers to Tevye, a father living in a shtetl named Anatevka in an obscure corner of the Russian empire who’s “blessed with five daughters” as his character says with heavy emphasis in the movie, which came out in 1971. (In the stories, he has seven.)

Tevye’s five daughters

Tevye’s five daughters

When it comes time to marry, Tevye’s daughters rebel, each pushing the envelope a little farther. Tzeitel, the oldest, refuses to consent to marry the old widower Anatevka’s matchmaker picks out for her, insisting that she marry a young penniless tailor named Motel for love. Tevye relents, concocting a crazy excuse for countenancing the marriage.

Next, his daughter Hodel refuses to marry a religious Jew, choosing instead to follow a young secular Jewish Communist named Perchik to Siberia.

Finally, at the end of the film, the next youngest daughter, Chava, breaks with Jewish tradition completely: she announces she’s marrying Fyedka, a non-Jewish local man. In the Broadway musical and subsequent movie, Tevye agonizes, then ultimately gives his blessing to the match, telling the couple “God be with you.” In the original stories, Tevye remains steadfast, refusing to countenance the match. (The original stories are also darker in tone, with his other daughters suffering difficult trials and sad fates.)

Sholem Aleichem was the pen name of Sholem Rabinivitz. Born in 1859 into a middle-class family in the prosperous town of Pereyaslav in the Ukraine, he grew up speaking Hebrew and Russian as well as Yiddish. He always said he based his Tevye stories on a real-life milkman named Tevye he once met in a tiny Jewish shtetl who had a wry way of looking at the world and was committed to his Jewish religion. Sholem Aleichem wrote him as a comic character and envisioned him being portrayed on stage; a 1919 Yiddish play did capture Tevye’s stories to an appreciative Yiddish-speaking audience, followed by a Yiddish movie produced in 1939

By the time the Broadway musical and Hollywood film came along, the shtetls that Sholem Aleichem had describe were long gone: over 6 million Jews had been murdered in the Holocaust just a generation before. Sholem Aleichem, like so many other European Jews, had moved to the United States. In the 1960s and 1970s, many American Jews were abandoning the tight-knit bonds that had held them together in immigrant neighborhoods and were moving to more affluent, spacious suburbs. Fiddler on the Roof came along at a time when nostalgia for the old ways of life was bumping up against the new, secular reality of American Jewish communities.

The musical conveys some of the joy of a traditional Jewish lifestyle. One of my favorite scenes takes place late on Friday afternoon. Tevye’s rounds have taken longer than usual because his horse is lame and he’s had to pull his heavy milk wagon himself. As he approaches his ramshackle home, his wife Golde tells him, “Hurry up, it’s nearly the Sabbath!” She’s already dressed in her fine Shabbat dress. Golde looks regal, her dress adorned with a strand of pearls. It’s a realistic scene in Jewish homes across the world each week: as sunset on Friday approaches, Jews don their finest clothes to prepare for a regal meal, as the lady of the home lights Shabbat candles.

Tevye feeds his animals (singing If I Were a Rich Man as he works), then washes up and changes into his Shabbat suit and kippah. He begins reciting prayers under his breath as he enters his home. Usually shabby, tonight it looks beautiful. Typically hard-working and harried, tonight Tevye and his family have time to relax and focus on one another. Tevye and Golde bless their children and Golde makes a blessing over her Shabbat candles. The musical gets the grandeur and holiness of Shabbat right.

Fiddler on the Roof also gets right the tightly-knit Jewish communities. A traditional Jewish community fosters a lot of togetherness: men typically pray together three times a day with a minyan; children attend Jewish schools or classes; women get together to study and recite Psalms. That community is evident in the world of Fiddler where the bonds that unite the dwellers of Anatevka are palpable. Norman Jewison, the non-Jewish director of the film, described sitting next to Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir (who grew up in a Yiddish speaking home in Ukraine) at the film’s premier screening in Israel, and watching her wipe away a tear.

One of my favorite songs in the musical is Do You Love Me?, sung by Tevye and his wife Golde after their daughter Hodel announces she is marrying a penniless young Jewish Communist named Perchik “for love,” without any involvement from a matchmaker or her family. When Golde objects, Tevye tells her Perchik “is a good man… I like him… And what’s more important, Hodel likes him. Hodel loves him. So what can we do? It’s a new world. Love.” Tevye starts to get up then suddenly asks Golde if she loves him.

Do You Love Me?

Do You Love Me?

Singing, they describe their own arranged marriage 25 years ago, when their parents told them that eventually, love would grow. “And now I’m asking, Golde, do you love me?” Tevye sings. In response, Golde describes all the ways they’ve worked together through the decades: she’s milked the family cow, raised their children, cooked and cleaned, and so much more.” “If that’s not love, what is?” she finally concludes.

Tevye - who’s slaved away through the years as well, building their family - gazes at her fondly as they finally realize they’re in love: “It doesn’t change a thing, But even so, After 25 years, it’s nice to know.”

This touching song conveys a deep Jewish truth: love grows through giving. The Hebrew word for love, ahavah, has as its root the word hav, “give.” Giving to another person helps us keep their needs and perspective in mind, and fosters closeness. When we give to another person, and particularly when we make the series of commitments to our spouses that marriage demands, we begin to foster the deep, abiding love that comes from being true life partners.

A lot of Fiddler on the Roof’s comedy comes from Tevye’s bumbling through quotes about Jewish topics. “As Abraham said, ‘I am a stranger in a strange land…’” Tevye confidently intones in one scene, only to be told that it was Moses who said that. “Ah. Well, as King David said, ‘I am slow of speech, and slow of tongue,’” Tevye replies - only to be told that this too was said by Moses. “For a man who was slow of tongue,” Tevye replies testily, “he talked a lot.”

The denizens of Anatevka are steeped in religious discourse, but in the Broadway and movie version there’s never any indication that they take it too seriously. The town’s rabbi is elderly and out of touch, and religious comments are confined to Tevye’s garbled pronouncements. That is a far cry from the way life was in actual shtetls and even different from the Tevye in Sholem Aleichem’s writings. “On the Shabbat, I tell you, I’m a king,” Tevye proclaims in the short story Tevye Strikes it Rich, before describing the Jewish books he studies on Shabbat: “The Bible, Psalms, Rashi, Targum, Perek, you-name-it….” It’s a far cry from the more ignorant Tevye of modern depictions.

The writer Pauline Wengeroff (1833-1916) wrote about her life in the type of close-knit Yiddish speaking Jewish communities that Fiddler on the Roof refers to. She and her husband were highly educated, fluent in German and Russian as well as Hebrew and Yiddish. Yet her husband, like most of the Jews they knew, spent long hours prioritizing Jewish study. “My parents were God-fearing, deeply pious, and respectable people,” she wrote in her masterful two-volume work Memoirs of a Grandmother. “This was the prevalent type among the Jews then, whose aim in life was above all the love of God and of family. Most of the day was spent in the study of Talmud, and only appointed hours were set aside for business….”

In a real-life shtetl like Anatevka, there would have been much more Jewish learning, and a greater familiarity with Jewish books and wisdom.

If there’s any song in Fiddler on the Roof that grates on my nerves, it’s the opening song Tradition! “Because of our traditions, we’ve kept our balance for many, many years,” Tevye sings. “Here in Anatevka we have traditions for everything - how to eat, how to sleep, how to wear clothes. For instance, we always keep our heads covered and always wear a little prayer shawl. This shows our constant devotion to God. You may ask, how did this tradition start? I’ll tell you - I don’t know! But it’s a tradition….”

Nonsense. A committed Jew like Tevye, who made the time to study Jewish texts, would be familiar with the sources for the Jewish practices he describes: he’d likely spend time studying about them each week. Jews don’t live Jewish lives merely because of “tradition”. On the contrary: they grappled with Jewish texts and eternal questions for most of their lives.

In Sholem Aleichem’s final Tevye story, after the residents of Anatevka have learned they must leave their town, Tevye is philosophical, relying on his deep faith to sustain him. As he packs up to leave, he quotes the Torah and Jewish prayers. He remembers how our ancestor Abraham was commanded by God to leave his family and his land too. Tevya hopes for the coming of the Messiah. And he takes our leave, saying he’s done talking, because now he has to go and be with his children and his grandchildren, who need him.

Like him, they were living a rich Jewish life, not out of tradition, but based in a deeply-held commitment to Jewish ideals.