Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

7 min read

A cautionary tale about being complicit in our own oppression.

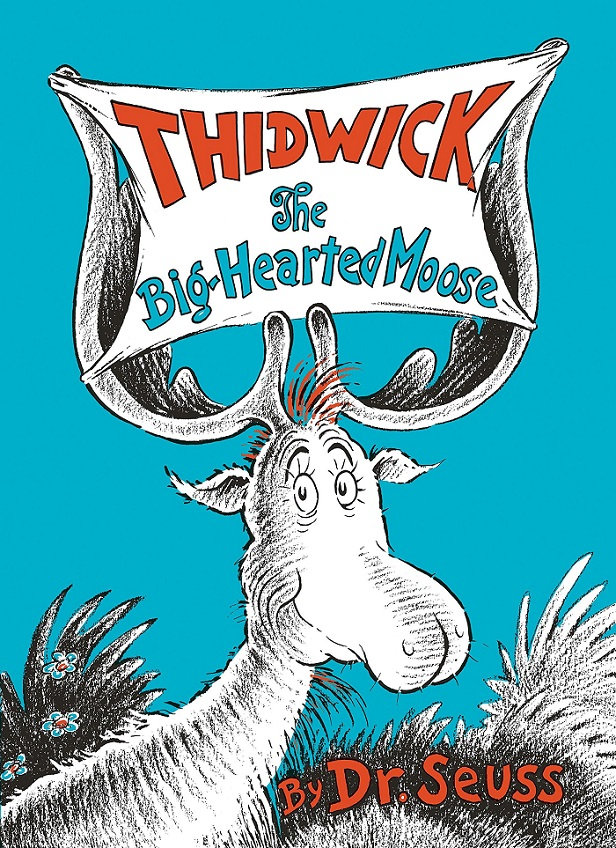

During the years my kids were small, the Jacoby household accumulated a lot of Dr. Seuss books, quite a few of which were read again and again and again. My favorite Dr. Seuss book, hands down, is Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose. (A close second is Yertle the Turtle, a paean to liberty and civil disobedience.) So when I read that Netflix had signed a deal to create animated shows based on five Dr. Seuss books, Thidwick among them, my first reaction was delight at the thought of all the boys and girls who would be introduced to Theodor Seuss Geisel’s masterpiece.

About 20 seconds later, though, it occurred to me to wonder whether Netflix would be true to the plot and message of Thidwick – or would recast them to fit a more watered-down agenda. Sure enough, the one-line description of the new project makes it sound like nothing more than a heaping spoonful of kumbaya.

When a grumpy moose leader decides that he wants to be the happiest moose in the pack, he calls upon sweet Thidwick to help him. As this unlikely duo embarks on a comical adventure, Thidwick discovers that the key to happiness is being kind to others.

Not to put too fine a point on it, that has exactly nothing to do with the story written by Dr. Seuss.

First published in 1948, Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose is a splendid parable about the limits of hospitality, the insatiability of free riders, the importance of self-respect, and the risk that unrestrained entitlements can hobble well-intended and productive members of society under a load they cannot bear.

As the story opens, Thidwick, a friendly and easygoing moose, is grazing along the northern shore of Lake Winna-Bango. When he is hailed by a Bingle Bug, who asks if he can hitch a ride on the moose’s antlers, Thidwick cheerfully assents: “There’s room there to spare, and I’m happy to share!/ Be my guest and I hope that you’re comfortable there!”

Almost at once, however, a Tree-Spider jumps aboard, invited not by Thidwick but by the Bingle Bug, who serenely declares that the moose won’t object because “he’s the big-hearted kind.” Then a “fresh little Zinn-a-zu-Bird” invites himself onto Thidwick’s antlers, reasoning that “if there’s room there for two, then there’s room there for three!” To which the bug replies gaily, “There’s plenty of room . . . and it’s free!”

The bird not only settles himself on the moose’s head without permission, he then begins “yanking hairs out of poor Thidwick’s head” – 204 of them, to be precise – in order to build a nest. He doesn’t apologize for the pain he causes, still less for appropriating the moose’s hairs without permission. He sees no need to, since Thidwick “can always grow more.”

Thidwick isn’t happy to find himself being abused in this way, but he resolves to be a “good sport” on the grounds that “a host, above all, must be nice to his guest.”

Soon Thidwick finds himself supporting a large population of mooches, including more birds (among them a woodpecker that drills holes in his antlers), a family of squirrels, a bobcat, and a turtle, all of whom quickly come to regard his hospitality as an entitlement that may not be curtailed. When the moss on the lake’s northern shore runs out, Thidwick faces starvation unless he can swim to the southern shore for food. But his “guests” refuse to countenance such a thing. They demand that the issue be put to a vote, with predictable results:

He stepped in the water. Then, oh! what a fuss!

“STOP!” screamed his guests. “You can't do this to us!

These horns are our home and you've no right to take

Our home to the far distant side of the lake!"“Be fair!” Thidwick begged, with a lump in his throat.

“We're fair," said the bug.

"We'll decide this by vote.

All those in favor of going, say 'AYE,'

All those in favor of staying, say 'NAY'."“AYE!” shouted Thidwick,

But when he was done,

“NAY!” they all yelled.

He lost ‘leven to one.“We win!” screamed the guests, “by a very large score!”

And poor, starving Thidwick climbed back on the shore.

Thidwick’s free riders aren’t finished imposing on his soft-hearted nature. Having asserted their entitlement to a property right in the moose’s antlers, they proceed to invite even more creatures to join in taking advantage of him:

They asked in a fox, who jumped in from the trees,

They asked in some mice and they asked in some fleas.

They asked a big bear in and then, if you please,

Came a swarm of three hundred and sixty-two bees!Poor Thidwick sank down, with a groan, to his knees.

He keeps telling himself that “a host, above all, must be nice to his guests” – but the uninvited squatters aren’t his guests, they are his abusers. They are violating Thidwick’s personal domain, appropriating his resources, and undermining his security. Worst of all, they claim to be doing so by right: After all, they voted and he lost! The author of Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose was a passionate opponent of fascism, but he understood that political and economic legitimacy requires more than the bare exercise of voting. Democracy, it has been said, is two wolves and a lamb voting on what to have for lunch. Thidwick conveys that message in terms even young children can understand.

Learn to say “no” when your self-respect and safety are at stake.

Why is the moose so reluctant to stand up for his right to dispose of what any reasonable observer knows is his alone? Hospitality and generosity are admirable qualities, but Thidwick clings to them even when they reach the point of self-abnegation. That isn’t admirable, it’s irrational. It is a threat to Thidwick’s own self-preservation. Fixated on being a “nice” host, he is on the point of sacrificing himself in order not to inconvenience his unwanted “guests.”

Here, too, is a message for young children: It is wonderful to be big-hearted, but don’t let yourself be intimidated by bullies who would take advantage of your good nature. You don’t have to acquiesce when someone wants access to your body, your property, or your labor. Learn to say “no” when your self-respect and safety are at stake.

Thidwick’s reluctance to stand up for his own interest – and to oppose the outrageous demands made on him by his freeloading passengers – come perilously close to causing his death. When hunters appear on the scene, the moose is too weighed down to race away on foot and too browbeaten by his tormentors to plunge to safety in the lake. At the last minute, serendipity intervenes:

Today was the day,

Thidwick happened to know . . .

. . . that OLD horns come off so that NEW ones can grow!

He sheds his antlers, escapes both the hunters and his parasitic squatters, and crosses the lake to a safe and happy ending.

“One way to interpret Thidwick,” writes Aeon J. Skoble , a professor of philosophy at Bridgewater State University, “is as a cautionary tale to the effect that we can be complicit in our own oppression.” This isn’t merely a fanciful children’s story about a moose who allowed an insufferable, self-righteous, and importunate menagerie to occupy his head and curtail his freedom. It is also an allegory about the dangers of keeping silent when confronted with insufferable, self-righteous, and importunate claims from people and groups whose demands are illegitimate and whose moral authority is spurious.

What a wealth of provocative ideas Dr. Seuss packed into Thidwick! What a pity that Netflix sees in such a remarkable book merely a vehicle for delivering pabulum.

This op-ed originally appeared in “Arguable,” a weekly newsletter written by Boston Globe columnist Jeff Jacoby.