Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

9 min read

The Olympic champion and Holocaust survivor devoted his life to philanthropy and Holocaust education.

Sir Ben Helfgott, who recently died at age 93, was a world-class athlete, a tireless advocate for Holocaust education, a major philanthropist, and an all-round mensch. Here are some incredible facts about his remarkable life.

Growing up in Piotrkow, a small town in Poland, Ben was surrounded by a warm and loving Jewish community that comprised almost a third of the population. Ben’s father Moshe ran a flour mill and his mother Sara stayed home to take care of Ben and his sisters Mala and Lucia. Ben’s two dozen cousins lived nearby.

Ben excelled in both school and sports. He won races against the other boys in the town and served as captain of his school’s soccer team. Years later, he credited his early love of sports with instilling a keen sense of sportsmanship and an inner strengthv “I could never have survived the Holocaust without that strength,” he later said.

After Germany invaded Poland in 1939, they immediately started targeting Jews. In Piotrkow, all Jews were ordered to move into a cramped section of town that was designated the Jewish Ghetto. They were in constant danger. Ben recalled how one day, the local Nazis transported hundreds to Jewish men - including two of Ben’s uncles - to a nearby Jewish cemetery. The Jews were ordered to enter the cemetery in single file; as each man entered the cemetery, he was shot.

Ben’s father realized that he and other Jews faced starvation in the Ghetto. He forged a pass allowing him to exit the ghetto for short periods of time, and made contact with some of his former Gentile employees who smuggled him small quantities of wheat to take back into the Ghetto. Inside the Ghetto, Moshe rigged up a small flour mill and produced small batches of flour for the Jews imprisoned inside.

When he was 12 or 13, Ben managed to get a “job” in a glass factory, lugging heavy boxes around the warehouse. He wasn’t paid for this work, but this slave labor managed to save his life. In 1942, when Ben was just 13 years old, Nazis took 500 Jews from the Ghetto to one of the town’s synagogues, and from there to a local woods. Deep in the woods, all 500 Jews were shot. Ben’s mother and his sister Lucia were among them.

Ben Helfgott, age 15, semi-reclining, far right

Ben Helfgott, age 15, semi-reclining, far right

Soon, Ben - along with his father and sister Mala - were recruited to work as slave laborers at another local business. They were kept imprisoned near a factory, where they worked each day making huts. Later in life, Ben refused to accept that he’d been exploited as a slave by the local businessman who owned the factory: his working conditions weren’t so terrible, he explained. Yet he, along with the other Jews who toiled in the factory were never allowed to leave. Instead of receiving any pay, they were given starvation rations to eat.

In 1944, the precarious safety that Ben, his father, and his sister had found in the factory came to an end. Faced with mounting losses on the battlefields, Hitler decided to speed up his annihilation of Europe’s Jews. The pace of Jews being sent to concentration and death camps quickened. Ben's sister Mala was sent to Ravensbruck, a concentration camp for women in Germany. Ben and his father were sent to Buchenwald, a fearsome concentration camp just outside the scenic German city of Weimar.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum describes the horrors that Ben and other inmates faced in Buchenwald:

“This area was surrounded by an electrified barbed-wire fence, watchtowers, and a chain of sentries, outfitted with automatic machine guns. Inside the main camp, there was a notorious punishment block, known as the Bunker….This is where prisoners who violated camp regulations were punished and often tortured to death.” Food was scarce and many prisoners died of starvation and disease. German doctors performed barbaric medical experiments on Buchenwald inmates. Periodically, prisoners were sent to nearby death camps to be gassed to death.

“It was a terrible place,” Ben later recalled. “All we had to eat was soup that smelled like urine and a crust of bread.”

In 1945, when Ben was just 16, Nazi forces abandoned Buchenwald. Ben was transferred to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. With 30,000 other Jews, his father Moshe was forced on a death march that killed tens of thousands of Jews. Moshe Helfgott tried to escape the death march and was shot dead by Nazi guards. Ben became an orphan, utterly alone in the world. He later described crying for days on end, mourning for his parents and sister.

After the war, a major British Jewish charity wanted to do all it could to help child Holocaust survivors. The Central British Fund for Jewish Relief and Rehabilitation was formed in 1933 after Hitler was elected Chancellor of Germany, and worked tirelessly for years to help bring Jewish refugees out of Europe to England to British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. In 1945, the group obtained permission from British authorities to bring one thousand child Holocaust survivors to Britain.

Tragically, they couldn’t find that many children who were still alive. In the summer of 1945, 735 child survivors were brought to England; Ben was one of them. He tried returning to Piotrkow after the war and was attacked by antisemites there. It was clear that he couldn’t remain in Europe; moving to England seemed like his only chance: “I knew I wanted to go.”

The survivor children (even the girls) dubbed themselves “The Boys” and made bonds for life.

Ben was housed in a camp in Windermere, a scenic area of northwest England, with other children. He described it as being “like heaven”.

Ben thrived in Windermere and later in London, learning English quickly, gaining entrance to a prestigious grammar school and earning high grades. He began to play sports again. Years after the war, he found out that his beloved sister Mala had also survived; they were reunited in England in 1947.

“The Boys” became close friends for life, and their children and grandchildren continue to enjoy deep friendships to this day.

Paul Mayer - known as Yogi - was a major presence in the north London Jewish community at the time. He’d been born in Germany. A gifted athlete, Yogi was widely expected to compete in the 1936 Olympics on Germany’s national swimming team, until the Nazi government forbade Jewish athletes from representing the country.

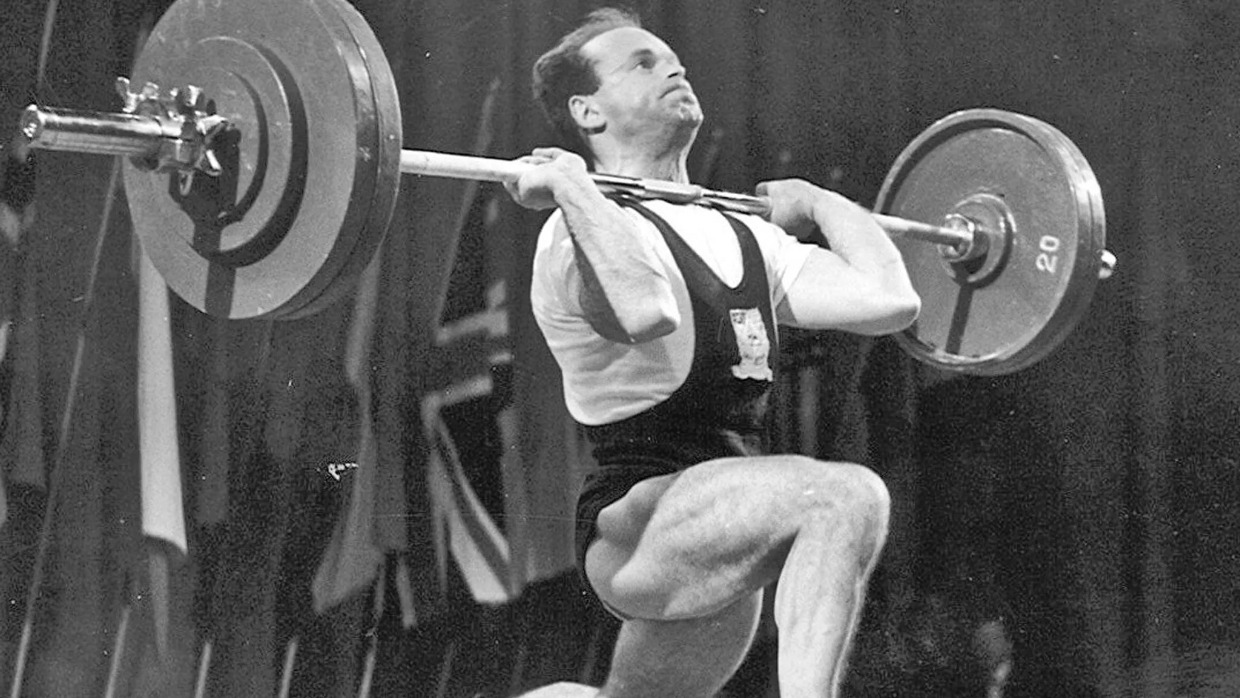

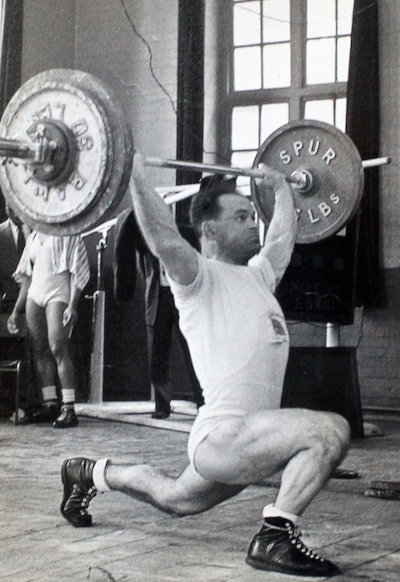

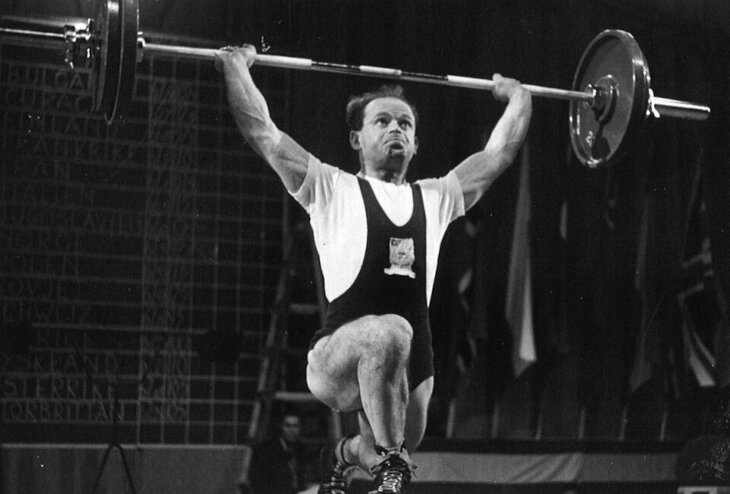

In 1939, Yogi, along with his wife Ilse and their young son, fled Germany, moving to Britain, where Yogi volunteered for the British army, working in Special Operations. After the war, he settled in north London and began to run a sports club for Holocaust survivors, known as the Primrose Youth Club. Ben Helfgott was one of his star athletes. Yogi encouraged him to focus on weightlifting, which was one of his particular strengths.

Only two Holocaust survivors ever competed in the Olympics. One was Alfred Nakache, a French swimmer who competed in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. He and his wife Paule had a chance to escape to Spain with a clandestine Jewish smuggling group, but they turned it down because they feared that their toddler daughter Annie would cry and give away the location of their fellow Jews. The family was sent to Auschwitz, where Alfred’s wife and baby daughter were murdered. Alfred survived, and represented France in the 1948 Olympics in London.

Ben Helfgott was the only other Holocaust survivor to compete in the Olympics.

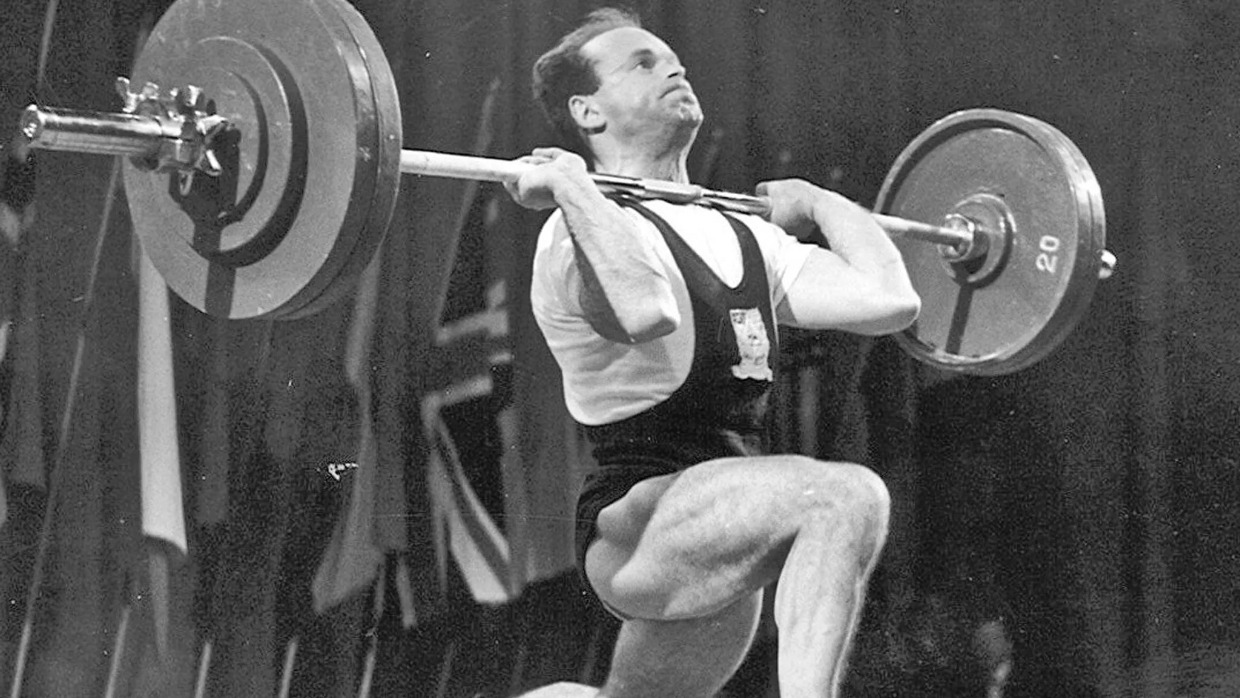

Ben was captain of the British Olympic weightlifting team at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne. He also represented Britain in the 1960 Rome Olympics. “Whenever I pulled on that GB (Great Britain) vest I wanted to do well; I so wanted to win a medal to say thank you to the country that saved me,” he said.

Ben also won gold medals at the World Maccabiah Games - the “Jewish Olympics” - in Israel, where he represented Britain in 1950, 1953, and 1957.

He was the last person to see the Israeli athletes before they were murdered in the 1972 Munich Olympic Massacre.

In 1972, Ben was an official in the Munich Olympics, where Palestinian and German terrorists murdered 11 Israeli athletes and a West German police officer, while German Olympic officials insisted that the games continue.

“I was with them until about 1:30 am,” he recalled; “speaking and drinking coffee. Then, at 7:30 am I was woken by a phone call, telling me they had been taken hostage. I have never forgotten them.” (Quoted in The Boys: The Story of 732 Young Concentration Camp Survivors by Martin Gilbert (Holt Paperbacks: 1998).

Ben Helfgott was a tireless advocate for needy Holocaust survivors. In 1963, he set up the ‘45 Aid Society, to raise awareness about the Holocaust and to provide material aid to poor survivors. Angela Cohen, the current Chairwoman of the ‘45 Aid Society, recalls that Ben “started talking about Holocaust before anybody else and made it an easy open door for people to talk about Holocaust whether they were a survivor” or not. “The difference that he has made has been incredible and enormous.”

Ben became a well-known figure in Britain. He served on the boards of a number of prominent Holocaust organizations and never missed an opportunity to educate people about the Holocaust. He was knighted in 2018, and afterwards was known as Sir Ben Helfgott.

Ben married Arza Helfgott in 1966; the couple had three sons and nine grandchildren.

After Ben’s death on June 16, 2023, Britain’s Prime Minister Rishi Sunak noted “Sir Ben Helfgott…survived the worst of humanity. His legacy is the ultimate triumph over that darkness.”