An Open Letter to Mayor Zohran Mamdani

An Open Letter to Mayor Zohran Mamdani

5 min read

8 min read

33 min read

6 min read

5 min read

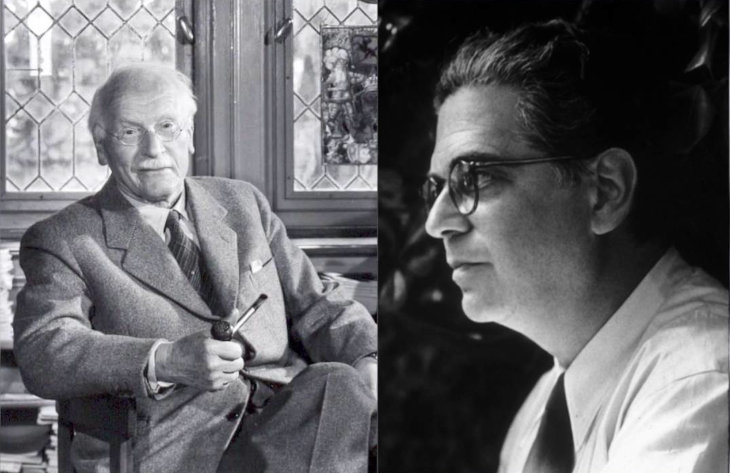

Based on his understanding of Jewish texts, a leading psychoanalyst of the 20th century took Carl Jung to task on the issue of personal responsibility.

In the summer of 1933, Erich Neumann, a young Jewish doctor who would become one of the leading psychoanalysts of the 20th century, fled Berlin with his wife and one-year-old son. Fresh out of medical school, he hoped to begin training as a psychoanalyst, but new anti-Jewish laws made it impossible. It was time to find a new home.

On their way to Mandatory Palestine, the Neumanns stopped in Zurich, where Erich could receive training from one of the greatest psychoanalysts of the age—Carl Gustav Jung, a student of Freud and founder of analytical psychology. It was a meeting that would profoundly shape both men, generating some of the most important psychological discoveries and controversies of the century.

After months of training, Neumann arrived in his ancestral homeland as a devoted disciple of Jung, eager to disseminate his teacher's theories. At the same time, he was struggling to understand what it meant to be a Jew during this catastrophic period in Jewish history. Separated from his parents and his new mentor, Neumann was on his own.

Neumann wrote The Roots of Jewish Consciousness between 1935 and 1945, under the shadow of the Holocaust. It was his attempt to articulate the uniqueness of the Jewish worldview and the particular challenges facing it in modernity. Beginning with the story of Mount Sinai, he highlights that the original plan had been for the entire Jewish nation to receive the entire Torah, but they were overwhelmed after receiving the first two of the Ten Commandments through Divine revelation and asked Moses to serve as their intermediary.

“Most characteristically, the Jewish genius allows its foundational story… to begin with its own catastrophic failure,” writes Neumann, who goes on to praise this “recurrent trait—the ability not only to look one's own shadow in the eye, but also to see the dynamics of life playing out in the conflict with that shadow… This tension, between a clear vision of failure and an obdurate ‘nevertheless,’ is one of the driving forces of all Jewish existence.”

In Neumann's view, the Israelites’ acknowledgement of their failure revealed their greatest strength—their embrace of personal responsibility and continuous growth. Neumann's insight echoes earlier Jewish sources. In Deuteronomy, Moses informs the Jews that God was pleased with their request for an intermediary. The medieval commentator, Don Isaac Abarbanel, explains that although their request appeared improper, God recognized that it stemmed from a humble acceptance of their limitations and a desire to fulfill the Torah nevertheless. Unfortunately, Neumann would soon learn that his cherished mentor did not share his view.

Carl Jung and Erich Neumann

Carl Jung and Erich Neumann

After the war, Neumann wrote a work on psychology and ethics. Sending a draft to Jung for approval, he was stunned by many of Jung’s proposed corrections that seemed to downplay personal responsibility. “I do not wish to discourage activity,” wrote Jung, but then added, “We can only learn how a grain of corn must behave between hammer and anvil.” Jung's point was that we are all overwhelmed by powerful forces—whether the dynamics of the unconscious psyche or the demands of physical existence. Though we might consider ourselves autonomous moral agents, true ethics means resigning ourselves to our circumstances.

Neumann boldly rebuffed his teacher. “The ethical behavior of the personality cannot only experience itself as the grain of corn between hammer and anvil,” he shot back. Neumann had chosen his Jewish convictions over Jung's psychological theories. Judaism champions the importance of personal responsibility. Already centuries earlier, Maimonides had written that one must never entertain the idea that life is predetermined: “There is no one who forces him, decrees upon him, or draws him to one of two paths. Rather he, of his own volition and understanding, inclines towards whichever path he chooses.”

But this was neither the first nor the most dramatic instance of Neumann's disagreement with Jung.

As the Nazis came to power, Jung had chosen not to openly oppose them. Worse still, his writings during the 1930s contained statements that were blatantly antisemitic. Neumann was shocked at his mentor's ignorance and lack of foresight. How could he not see what was brewing in Germany?

Neumann knew that his teacher was no Nazi, and declassified documents reveal that Jung eventually became an undercover agent for the OSS, the predecessor to the CIA. But Neumann also recognized that Jung's early misconceptions about Jews stemmed from ignorance, and he upbraided his mentor for his “general ignorance of things Jewish.” It seems that Jung took his pupil's words to heart. James Kirsch, another Jewish student of Jung, records that Jung personally apologized to his Jewish patients and friends. He began to explore Jewish mysticism and ultimately credited an early Hasidic leader, Rabbi Dov Ber of Mezeritch, with having “anticipated my entire psychology in the 18th century.”

Neumann's rebukes and Jung's repentance are beautiful examples of what can happen when a humble teacher encounters a bold and principled student. But they are also a cautionary tale. Even an experienced psychoanalyst can fail to see the blind spots in his own psyche. Without a focused attempt to understand foreign perspectives, we are all potential victims of baseless hatred.

Similarly, Jung's reduction of personal responsibility to the helpless “grain of corn” can easily yield a victim mentality. It will always be tempting to see ourselves as oppressed by cosmic forces that lift the blame for our personal failings. Particularly today, when social media and identity politics encourage us to reduce individuals to their social circumstances, we are at risk of losing our belief in the individual's ability to transcend their environment. In response to this, Neumann encourages us to contemplate what happened at Mount Sinai, where a small nation recognized its limitations, embraced them, and marched courageously forward into history.

Jung’s alleged antisemitism seems rooted more in misunderstanding than intent. Using Sigmund Freud, an atheist who rejected Judaism, as his example, Jung infamously claimed, “the Jew is especially bound to the earth and favors empirical rationalism and intellectualism,” but this stems from his limited exposure to authentic Jewish thought.

Freud’s (and his Jewish disciples) rebellion against Judaism does not represent the religion itself, which is steeped in spirituality and mysticism. Jung never truly engaged with "Jewish" Jews who embody these mystical traditions. Had he done so, he might have seen that Judaism, far from being purely rational, delves deeply into the metaphysical and spiritual—ideas closely aligned with Jung’s own psychological theories.

Max, Great comment. Thank you.

Fascinating and well-written; thank you!

It occurs to me that the idea of personal responsibility and what that implies (e.g., a code of ethics, a moral conscience, etc.) is one of the factors that so irks Jew-haters.

Right

Wow, transformative!

Yes it is