Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

6 min read

A Tennessee school board’s decision to remove the Pulitzer-prize winning book from its curriculum furthers the ever-increasing ignorance about the Holocaust.

While much of the world prepared to mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day in January, 2022, one school district in Tennessee decided to remove the two-volume Holocaust graphic novel Maus: A Survivor’s Take from their school curriculum.

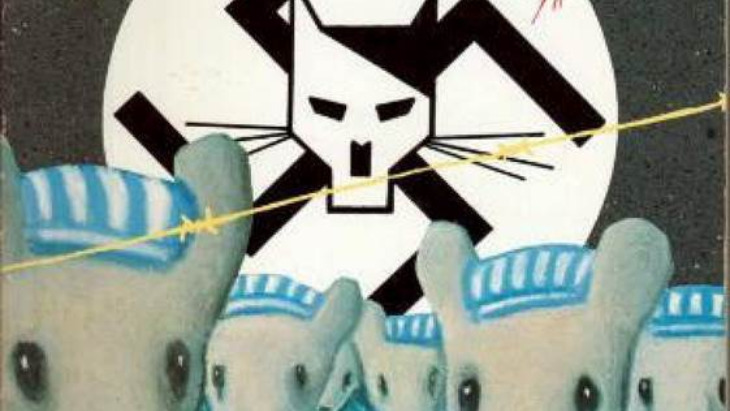

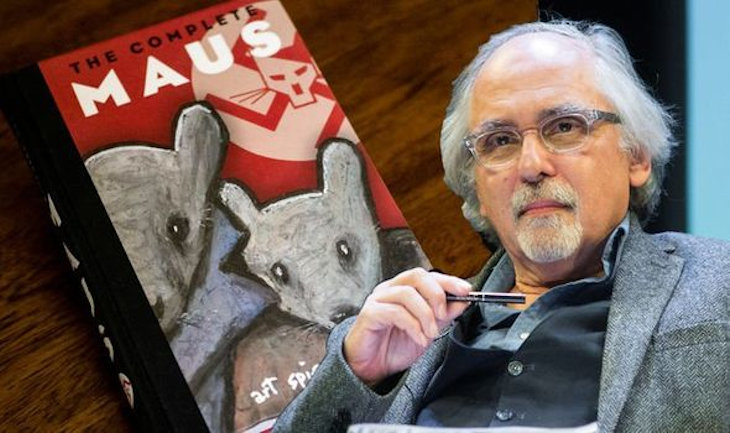

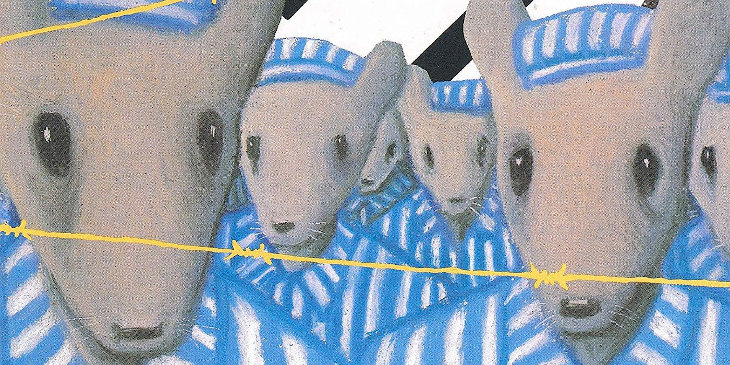

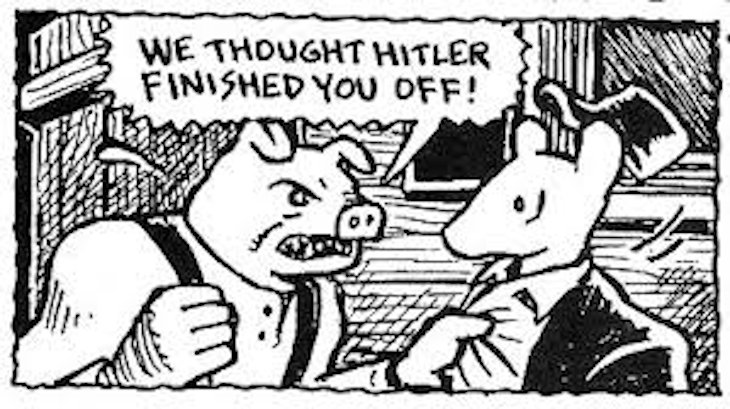

Art Spiegelman, a prominent cartoonist and the son of Holocaust survivors, published the first volume of Maus in 1986 and the second volume in 1991. This unusual work, which describes Spiegelman’s father’s harrowing experiences during the Holocaust, won a Pulitzer prize for best fiction, the first and only graphic novel to do so. All of the characters in Maus are drawn as animals. Jews are depicted as mice, Nazi as cats, Poles as pigs, and Americans as dogs.

The books toggle back and forth between an adult son’s conversations with his father, who is an unhappy, crotchety old man, and the terrible memories his father describes. The effect is both to draw readers in with compelling illustrations and dialogue, while also providing some sense of distance from the terrible story within Maus’s pages.

Reading Maus can be a grueling experience. Volume I is subtitled “My Father Bleeds History” and begins with the son, an artist named Art, visiting his father Vlatek and his father’s wife Mala. The names are those of Art’s actual family. During the Holocaust, Art Spiegelman’s parents, Anja and Vlatek, endured terrible hardships and survived Auschwitz. Anja Spiegelman died by suicide in 1968.

Vlatek begins to describe his once happy life in Poland in the 1930s, but his memories soon grow dark. After the Nazis invaded Poland, food grew scarce. Jews were forbidden from taking part in an increasing portion of public life. Maus depicts the growing horror in bold black and white sketches, which fit the somber mood of the book. In one early panel, Vlatek returns home looking upset. “There was another riot downtown today,” he tells his wife and young son. “Everyone yelling, ‘JEWS OUT! JEWS OUT!’ …Even two people killed. The police just watched!”

Vlatek and Anja watch as their friends and relatives are murdered one by one. They send their son Richieu away to live with his aunt in a different town, hoping he will be safe there, only to learn that when Anja’s sister discovered that all of the Jews in her town were about to be deported to Auschwitz, she poisoned herself, her two children, and Richieu. Volume II, subtitled “And Here My Troubles Began,” describes Vlatek’s experiences in Auschwitz, where he was forced to remove the remains of Jews who’d been murdered in the gas chambers.

Novelist Umberto Eco observed that “Maus is a book that cannot be put down, truly, even to sleep…slowly through this little tale comprised of suffering, humor and life’s daily trials, you are captivated by the language of an old Eastern European family…” When it first came out, the Los Angeles Times called it “enormously effective…an extraordinary accomplishment, a new way of looking at experience” of the Holocaust.

Author Art Spiegleman

Author Art Spiegleman

Maus’s raw power made it a natural choice for teachers in McMinn County, Tennessee, who have used it as an “anchor text” for their 8th grade English class’s months-long unit on the Holocaust. Yet there have long been some complaints in the district.

Some parents objected to images of naked mice in the Auschwitz scenes. Some also complained about the book’s use of profanities in some of its dialogue. To assuage these concerns, teachers in the district covered up the images of naked mice and swear words in the text. Yet objections remained.

McMinn County teachers were meant to begin assigning Maus to this year’s 8th grade students in January 2022, but they waited, sensing that the book might be banned. And that’s what happened after an acrimonious school board meeting on January 10. “It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids,” complained school board member Tony Allman. “Why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff?” he questioned. “It is not wise or healthy,” Allman declared at the meeting.

Some people present at the meeting defended Maus. “I was a history teacher and there is nothing pretty about the Holocaust and for me this was a great way to depict a horrific time in history,” explained Julie Goodin, an instructional supervisor in the district. The district’s other instructional supervisor, Steven Brady, defended the book, saying “When we think about the author’s intent, I could argue that his intent was to make our jaws drop. Oh my goodness, think about what happened.”

Their defense fell on deaf ears. In a unanimous vote, the 10-member McMinn County school board voted to remove Maus from the district’s curriculum. In a statement on Thursday, January 27, they defended their actions, explaining that Maus is inappropriate because “of its unnecessary use of profanity and nudity and its depictions of violence and suicide.”

Yet Mr. Brady and Ms. Goodin captured why it is crucial that books like Maus are read. The Holocaust was a uniquely horrific event in history. It’s not easy or pleasant to study it. But if we don’t remember the Holocaust, if we don’t arm ourselves with the knowledge of what happened and honor the memory of the Holocaust’s millions of victims, then we have learned nothing.

As the Allied forces advanced on Auschwitz 77 years ago in January 1945, the Nazis responded by desperately trying to erase evidence of their crimes. They dynamited the gas chambers in which nearly a million Jews had been murdered. They forced 60,000 Jews on death marches through the freezing January winter towards Germany so that when Allied troops finally entered Auschwitz, they wouldn’t witness the full extent of the Nazis’ crimes.

In many quarters, those attempts to erase and minimize the world’s knowledge about the Holocaust are still going on. Holocaust distortion and denial are rampant, and they’re having an effect. A 2020 survey showed that 63% of American millennials didn’t know that six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. Globally, only 54% of people have even heard about the Holocaust. Ignoring or minimizing the Holocaust is being complicit in the Nazi effort to hide their depravity from posterity.

When I heard about McMinn County’s school board removing Maus from the 8th grade curriculum, I asked my own son, who’s also in 8th grade, what he thought. To the objection of Maus’s nudity, he was incredulous: “They’re naked mice!” he pointed out, not people. “Maybe this was just an excuse,” he wondered.

One school board member who objected to Maus at the meeting, Mike Cochran, said he didn’t object to students learning about the Holocaust in general. Maus was simply too disturbing a book for kids to read. Yet the Holocaust is disturbing. And with so much ignorance about the Holocaust today, it’s more important than ever that we ensure the Holocaust is being taught effectively in schools, and that we educate ourselves and our communities.

Art Spiegelman’s two volumes of Maus is a good place to start.