To The Protesters in America Calling for an Intifada

To The Protesters in America Calling for an Intifada

12 min read

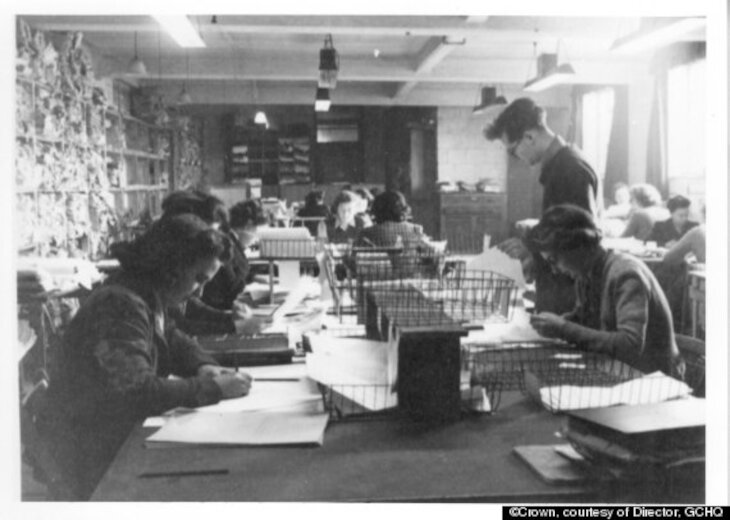

Meet some of the unsung heroes who deciphered enemy communications which proved crucial to winning the war.

Many unsung heroes contributed to the Allies’ victory in World War II. Some of those heroes’ work was strictly classified. Among them were Jewish codebreakers who managed to decipher enemy communication, which was crucial to winning the war. They provided crucial information to the Allies and saved countless lives. With the passage of time, we are learning more about their role in winning the war.

Wolfe Friedman was born in 1891 in Kishinev, which is currently in Moldova but back then was part of the Czarist Russia. His father, a Romanian Jew, worked as an interpreter and translator for the Russian Postal Service. His mother, Rosa, was a native of Kishinev and a daughter of a Jewish wine merchant.

The Friedmans lived a comfortable life but it was always overshadowed by antisemitism. Afraid of pogroms, the family left Russia for America when Wolfe was one year old. They settled in Pittsburgh where Wolfe’s father became a door-to-door salesman of Singer sewing machines. The family struggled, never quite managing to make ends meet. They also didn’t manage to escape antisemitism, though in America, it was much more covert than the violence of Russian pogroms. When the Friedmans received U.S. citizenship, they officially changed their son’s name to William.

William Friedman at work. (National Photo Company Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

William Friedman at work. (National Photo Company Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Bright and inquisitive, William studied genetics in college and was later hired by Colonel George Fabyan, an eccentric millionaire who strove to put his fortune to good use by establishing his own scientific laboratory on his vast estate, the Riverside, near Chicago.

The scientists and their assistants employed by Colonel Fabyan studied and conducted experiments in all aspects of science. While conducting studies in genetics, William met Fabyan’s numerous other employees with various areas of expertise. He was especially intrigued by the group occupied with cryptology. Among the group was his future wife, Elizebeth.

The year was 1915, and cryptology was in its infancy. Derived from the Greek words kryptos – hidden, and logos – word, cryptology is, according to Encyclopedia Britannica, “science concerned with data communication and storage in secure and usually secret form.” Cryptology encompasses both converting a message into code and back, called cryptography, and breaking the code of a secret message, called cryptanalysis.

Coded messages have been part of military communication since antiquity. A relatively simple technique, called Caesar cipher and attributed to Julius Caesar, involves substituting each letter in the original message by a letter some fixed number of positions down the alphabet. For example, if the number is 3, the letter A would be substituted by a letter 3 positions down, which is D. In order to decode the message, its receiver would need to know the number. A codebreaker who doesn’t have access to the number can try different numbers one at a time and see if the transformed message makes sense.

William and Elizabeth Friedman

William and Elizabeth Friedman

When William Friedman encountered cryptology at Riverside, he did not consider its military implications. Those were days of peace, and the researchers at Riverside were looking for hidden codes in Shakespeare’s plays. When, years later, William was asked what drew him to cryptology, he named “an inherent curiosity to know what people were trying to write that they didn’t want other people to read1.”

In 1917, the United States entered World War I, and William’s interest in cryptology turned from academic to practical. Colonel Fabyan offered his services to the U.S. Intelligence Office. At the time, the U.S. military did not have a cryptology department, and they took Colonel Fabyan up on his offer.

William and his new wife Elizebeth were thrown into deciphering intercepted enemy communication, as well as training others in the craft. Elizebeth recalls2:

We had a lot of pioneering to do. Literary ciphers may give the swing of the thing, but they are in no sense scientific. There were no precedents for us to follow. We simply had to roll up our sleeves and start a new course.

Over the course of the war, William not only assisted the U.S. government in securely encoding their own messages and decoding those of the enemy but also systematized the emergent science of cryptology, applying to it the existing mathematical and statistical knowledge. He wrote a series of scientific papers that later became cryptology’s foundation.

While the United States began its foray into cryptology during World War I, the British had been intercepting and decoding secret messages since the days of King Henry VII in the 16th century. During World War I, the British intercepted tens of thousands of German messages and broke the encryption codes. They collaborated with their counterparts in the United States, including the Friedmans. Both countries used the obtained information to influence the course of the war.

After World War I, Britain established its Government Code and Cypher School, combining the navy and military intelligence departments. In 1938, Admiral Sir Hugh Francis Paget Sinclair, head of British Secret Intelligence Service, purchased a mansion known as Bletchley Park to house the school.

Interestingly enough, the mansion had previously belonged to a prominent Jewish Leon family, relatives of the renown philanthropists Montefiores. To this day, the Leon family’s coat of arms is inscribed at the entrance to the mansion.

Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park

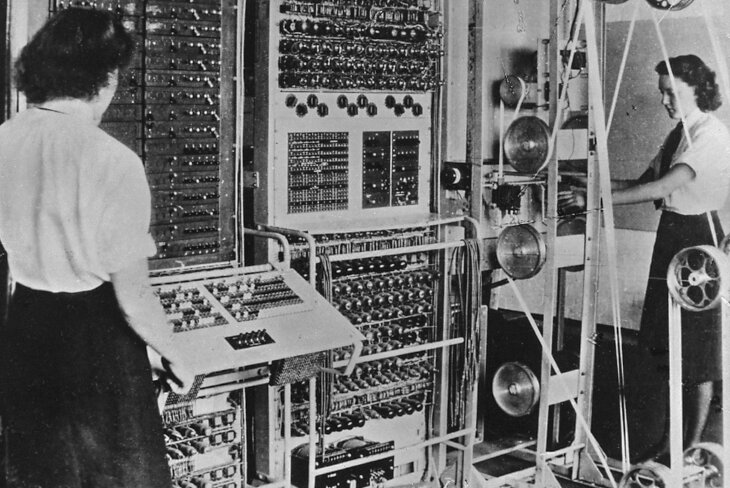

During World War II, between seven and eight thousand people worked at Bletchley Park, encoding and decoding secret messages around the clock. Among the staff were many Jews.

Even though the British were actively seeking talented codebreakers, it was not easy for a Jew for be hired by a government office due to an undercurrent of antisemitism. Anne Ross moved with her family from London to Bletchley in 1940 to escape German bombings. She applied for a job at Bletchley Park.

Author Martin Sugarman writes3:

[Anne] was interviewed by a civilian male in October 1940; he placed a revolver on the desk during the interview. He tried to tell her that as a Jew, she was not British enough but she argued the case of her 17th century antecedents and there was no answer to that. Her feeling at the time was that the interviewer was very anti-Semitic. However, her super typing skills got her the job…

The Bogush family were also evacuees from London. Their two daughters, Anita and Muriel, worked at Bletchley Park. The family often invited other Jewish employees to Shabbat meals at their home.

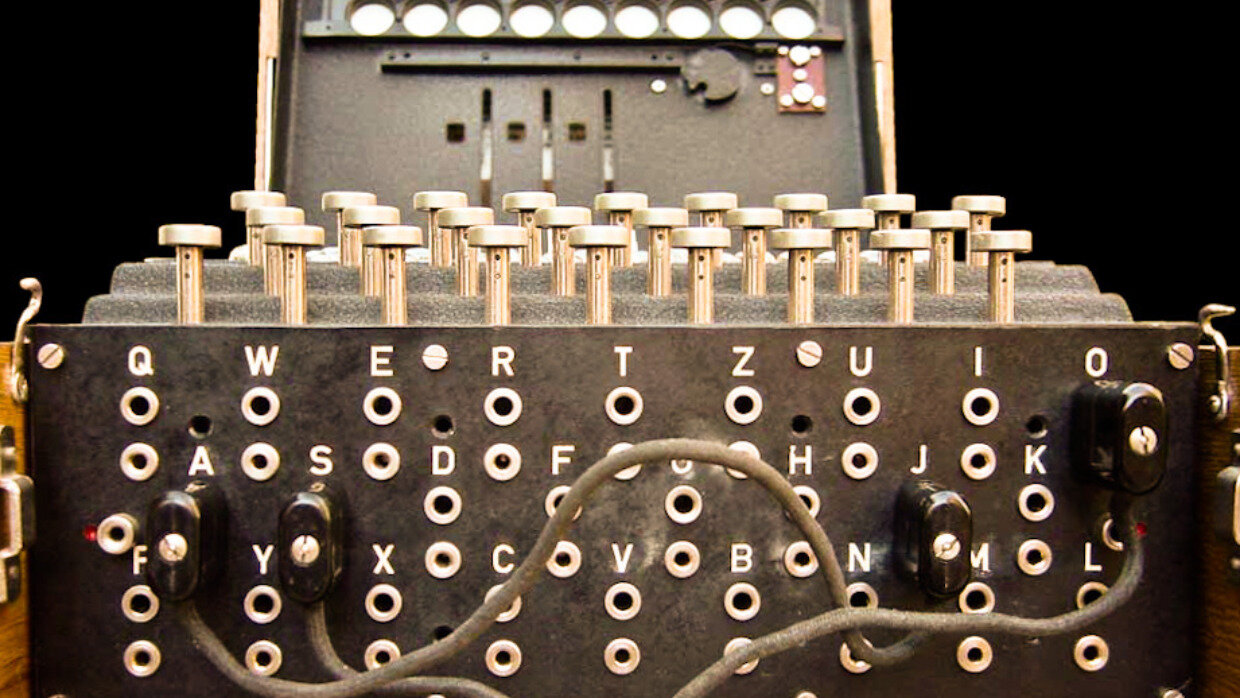

The Colossus computer at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, England, c. 1943.

The Colossus computer at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, England, c. 1943.

Bletchley Park administration was not particularly supportive of Shabbat observance. However, talented codebreakers were tolerated even when they insisted on taking every Shabbat off.

Among Shabbat observers was Walter Ettinghausen, a German-born head of the translation group, who was loved and admired by the staff. Walter was heavily involved in deciphering the messages that enabled the British to track down and sink the German battleship Bismarck.

Jewish employees brought their own kosher sandwiches to work or chose the foods they could eat from the canteen provided by the administration. Another Jewish employee, Morris Hoffman, recalls that kosher food “was never a problem as he went vegetarian and was treated accordingly whether in digs or the canteen4.”

Before the war, Morris had studied German. At Bletchley Park, he had the job of translating the decoded German messages into English. The most challenging part was determining the precise locations of the places mentioned in the enemy messages.

Another staff member at Bletchley Park was Ruth Sebag-Montefiore, great-niece of the mansion’s original owners. She recalls5:

We were sending and receiving coded telegrams to and from agents in every war zone. Each agent and each codist had two identical books, one a paperback novel, the other filled with five-figure groups of numbers. To encode the telegram you encoded the first few words – which had to contain more than fifteen letters – of a line in the novel, indicating in figure code, the page, line and five consecutive letters – which represented numbers – chosen first – and the five-figure group in the numbers book, where you were starting the message. After turning the message into figures, agent and codist proceeded, by adding or deducting one group of figures from the other to encode or decode the telegram…. you never knew from day to day what messages would reveal. Incoming telegrams consisted of all kinds of news picked up by agents – safe houses for escaped POW’s and new agents, disappearance of agents, leaks, landing zones – as well as enemy troop movements, sightings of U Boats, targets for the RAF – and the number of “Z’s” indicated urgency, three being most urgent. All was sent to HQ for action.

Among the more senior staff at Bletchley Park was Ernst Fetterlein, who had worked as a cryptanalyst for the Russian Czar Nicholas II. After the Russian Revolution, he escaped to Britain and joined its Secret Service. By the beginning of World War II, Fetterlein was already retired, but he was recalled to active service and worked at Bletchley Park until his death in 1944. He participated in cracking the Floradora doubly encrypted code, considered unbreakable by the Germans and used extensively in their communication.

Women working at Bletchley Park (UK Government, Wikimedia Commons)

Women working at Bletchley Park (UK Government, Wikimedia Commons)

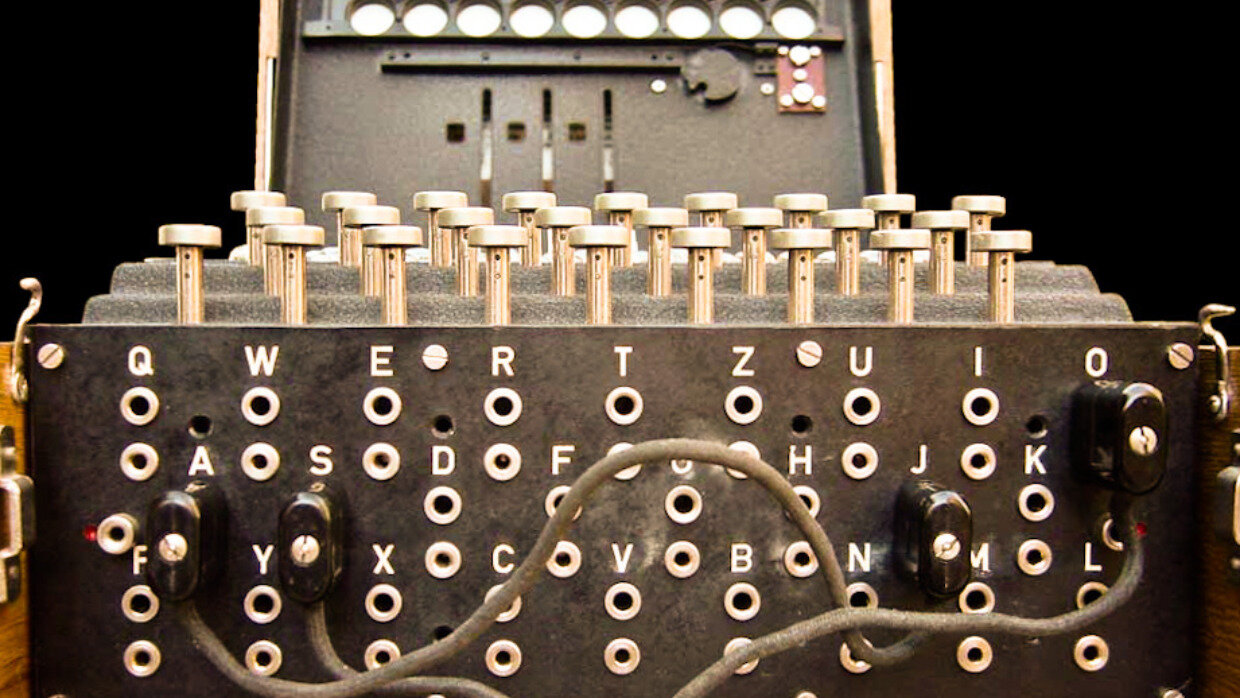

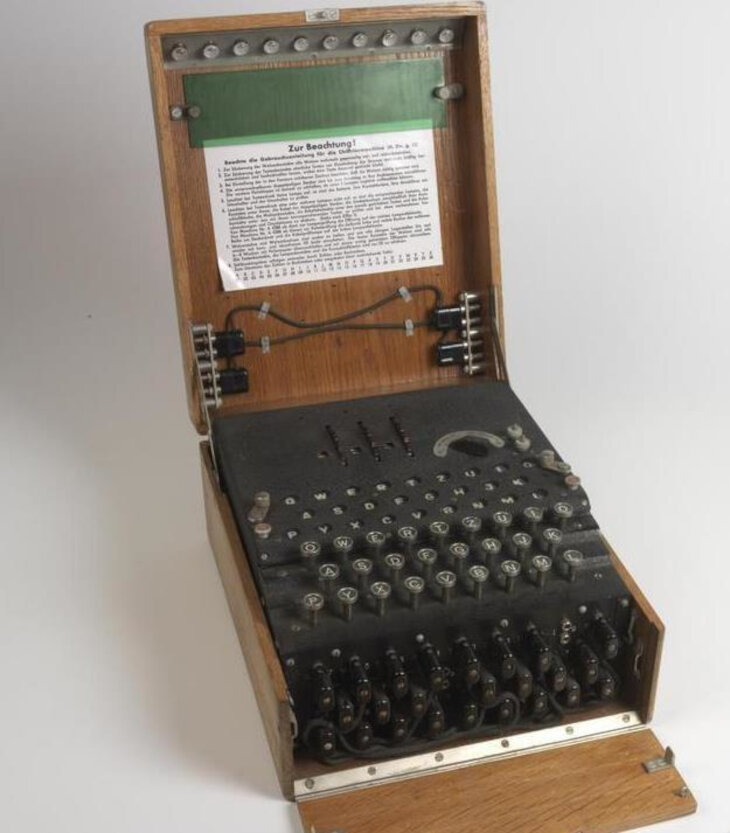

Among Bletchley Park’s team achievements is breaking the Enigma-encoded messages. Enigma was a typewriter-like machine that automatically encoded a message as it was entered by the typist. It was extensively used by the Germans during the course of World War II.

Among Jewish codebreakers who worked on Enigma was the British mathematician Jack Good. One night, Jack dreamed of a solution to a particular Enigma message. He tried it in the morning, and it worked. Jack also worked on another machine-generated code, Lorenz, that was used in messages between Hitler and his high command.

Another Jewish mathematician at Bletchley Park, Professor Maxwell Herman Alexander Newman, approached Enigma from another angle. He resolved to build a machine that would break the codes. By May 1943, Newman and his team built what became known as the Colossus, the predecessor of the modern computer. It is Newman who is credited with breaking the Lorenz code.

The Enigma machine

The Enigma machine

While codebreakers worked hard at Bletchley Park, William and Elizebeth Friedman and their team continued their codebreaking work in the U.S. In the 1930s, William invented his own encoding machine, which was used extensively by the U.S. military during World War II.

Another of William’s significant achievement in World War II is breaking the Japanese “Purple” code, enabling the U.S. to read Japanese military communication.

In 1941, William was sent to Bletchley Park. He oversaw the exchange of information, with the Americans receiving the Enigma and the British receiving the Purple code.

In 1942, the Axis forces, under the command of the German general Erwin Rommel, invaded Egypt from the Axis-controlled Libya. Rommel intended to conquer Egypt and move on to the Land of Israel, under British Mandate at the time. In anticipation of an easy victory, the Nazis were preparing to bring mobile gas chambers to Egypt and the Middle East and solve “the Jewish problem.”

As the Allies fought back, they noticed that Rommel seemed to be able to predict their every move. The codebreakers at Bletchley Park were tasked with finding his source of information.

What happened next was a chain of events that can only be described as a hidden miracle. Using the information they gained from Enigma-encoded messages between Rommel and the Nazi headquarters, the British codebreakers determined that the Germans broke the American code and were intercepting and reading messages sent by the U.S. military attaché from Cairo to Washington, D.C. The British urged the Americans to change their encoding.

The process took some time. Providentially, the last message the Germans were able to decipher informed Washington, D.C. that the British were planning to attack Rommel’s army at Mersa Matruh, an Egyptian coastal town halfway between the Libyan border and Alexandria.

Shortly after the American codes changed, the British changed their plans. Instead of Mersa Matruh, they attacked the Germans at another Egyptian coastal town, El Alamein. They took Rommel by surprise and defeated his army6.

Thus, the Axis forces were stopped before they managed to conquer Egypt and the Middle East, and the large Jewish communities in that area were spared.

British Infantry manning a sandbagged defensive position near El Alamein in 1942. Wikimedia Commons

British Infantry manning a sandbagged defensive position near El Alamein in 1942. Wikimedia Commons

For many years, the codebreakers’ work during World War II remained highly classified. The codebreakers were not allowed to discuss it even among themselves. Perhaps the Jewish codebreakers involved in breaking the German codes were not themselves aware of how their work saved many Jewish lives, but as more information becomes available, our appreciation for them can only grow.

Sources:

This article was an eye-opener. What's not to be thankful and admire?

What about Alan Turing and Bletchley Park? He was Jewish and was credited in inventing the modern computer. A film was made about him starring Benedict Cumberbatch.

Amazing

"The Woman Who Smashed Codes" by Jason Fagone is another book about Elizabeth Freidman and her husband. It's a great read!

Yes, it was a great read!

I was just going to suggest that book, I'm currently reading it. The Freidman's are considered the "parents" of the NSA. My father was a codebreaker during the Cold War.