Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

12 min read

If someone else's personality was somehow uploaded into your brain, would you then be that person?

If I’m not me, who the hell am I?

Douglas Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger) in Total Recall

If you know the work of Philip K. Dick, then you know that one of its central themes is the relationship between memory and personal identity. That is evident in many of the Dick stories made into movies, such as Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (which was adapted into Blade Runner, definitely the best of the Dick film adaptations); “Paycheck” (the inferior movie adaptation of which I blogged about recently); and A Scanner Darkly (the movie version of which is pretty good – and which I’ve been meaning to blog about forever, though I won’t be doing so here).

Then there are the short stories “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” (the first part of which formed the basis of the original Total Recall and its pointless remake) and “Impostor” (the basis of a middling Gary Sinise movie). These two stories nicely illustrate what is wrong with the “continuity of consciousness” philosophical theories of personal identity that trace to John Locke. (Those who don’t already know these stories or movies are duly warned that major spoilers follow.)

English philosopher John Locke’s view, famously, is that neither continuity of your body nor continuity of some immaterial substance could suffice in either case

What is it that makes it true that you are one and the same person as your 8-year-old self, despite the bodily and psychological changes that you have undergone since you were that age? What could make it true that someone existing after your death in heaven or hell would be one and the same person as you? English philosopher John Locke’s view, famously, is that neither continuity of your body nor continuity of some immaterial substance could suffice in either case. Rather, in his view, continuity of consciousness, and in particular memory, does the trick. You remember, or are conscious of, having done what your 8-year-old self did, which is why you are the same person as that 8-year-old. And if someone after your death was conscious of or remembered doing what you are doing now, that person would be the same person as you, so that you could be said to have survived your death.

Other thinkers since have raised various objections to this account, and philosophers sympathetic to Locke’s basic idea have modified it in various ways to deal with these objections. But the two Dick stories in question offer scenarios that point to what I consider the key problem with Lockean theories of personal identity.

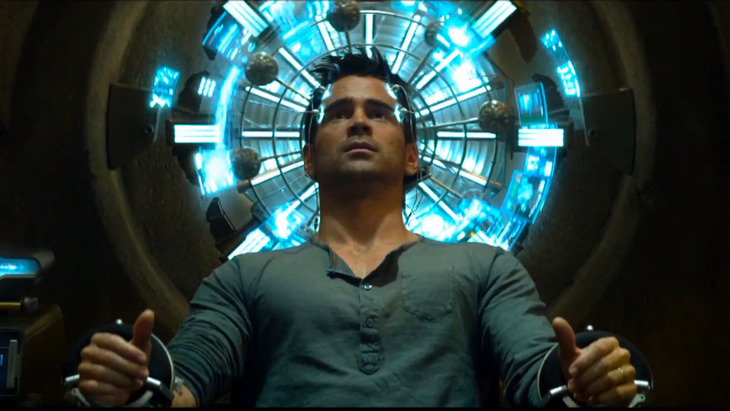

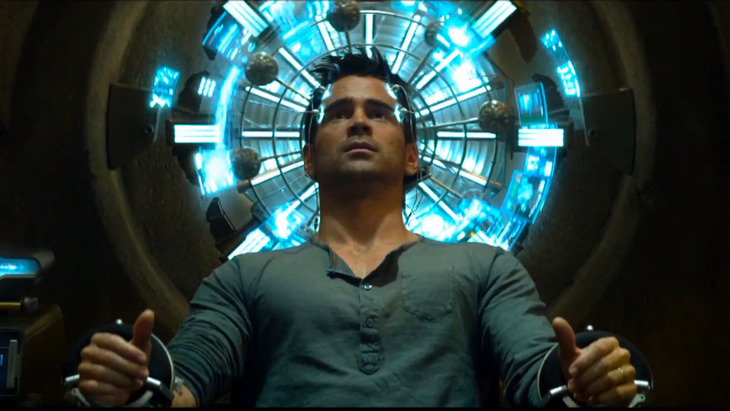

Total Recall, 1990

Total Recall, 1990

Start with “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.” Douglas Quail (renamed “Quaid” in the movie versions) is bored with his humdrum life and decides to visit the REKAL (pronounced “recall”) corporation, which will implant false memories of anything you want them to, make you forget you had them do it, and also plant various pieces of evidence around your house, etc. to reinforce the illusion that what you think you remember really happened. Quail’s request is that REKAL implant in him memories of having been a secret agent on a trip to Mars. In the course of beginning the implantation, however, REKAL employees discover that Quail already has repressed but genuine memories of having been a secret agent on Mars – that he really was such an agent and that his memory of being one has been imperfectly erased. Realizing that it risks getting itself involved in some matter of government intrigue, REKAL tries to disassociate itself from Quail altogether, and as his memories slowly return, Quail attracts the attention of government agents, who seek to kill him in order to maintain the cover-up of the work he had been involved in while a spy.

What is of particular interest for present purposes is a scene in Dick’s original story where Quail desperately begs the government agents to consider, as an alternative to killing him, a deeper memory wipe than they had attempted in their first, failed effort. Their reply is as follows:

“Turn yourself over to us. And we’ll investigate that line of possibility. If we can’t do it, however, if your authentic memories begin to crop up again as they’ve done at this time, then – “ There was silence, and then the voice finished, “We’ll have to destroy you. As you must understand. Well, Quail, do you still want to try?”

“Yes,” he said. Because the alternative was death now – and for certain. At least this way, he had a chance, slim as it was.

End quote. It isn’t clear just how thorough the proposed memory wipe is supposed to be, but Quail certainly seems willing to let it be complete if necessary. Note the stark, implicit contrast with what a Lockean theory of personal identity would lead us to expect. If Locke were correct, then for a person’s memories to be wiped away and replaced would be, in effect, for that person to go out of existence and for a new and different person to take his place. For Quail, though, such erasure and replacement is precisely a way for the original person to survive. Quail believes that he will still be Quail, that he will still exist, even if he gets a set of false memories, and that continued existence – rather than continuity of consciousness or memory – is what matters most to him.

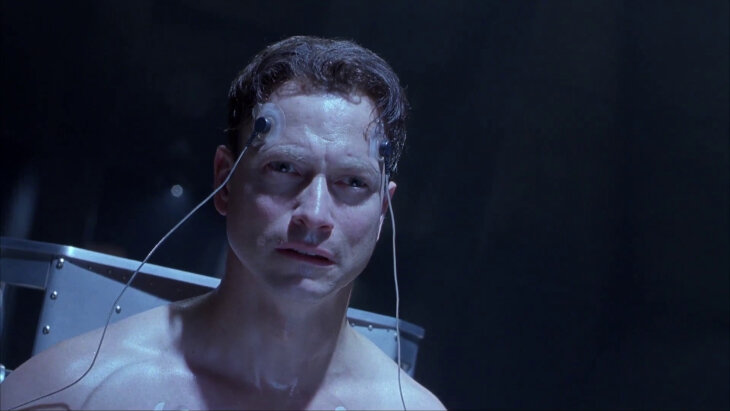

Now consider “Impostor.” In this story, the protagonist (played by Sinise in the movie version) is accused of being an android duplicate of government scientist Spence Olham, sent by the Martian enemy as an infiltrator. On the run, he hopes to find a way to prove that he really is the true Olham, as he certainly believes himself to be. And he does indeed find a way to convince his pursuers of this. It turns out, however – as he and his pursuers discover, too late and to their horror (given what the discovery entails in the context of the story) – that the true Olham is dead and that our protagonist really was an impostor after all. The Martian plot was so perfect that even the infiltrator himself wasn’t “in on it.”

Imposter, 2001

Imposter, 2001

Here the impostor remembers perfectly, or seems to anyway, being Olham, doing the things Olham did, and so forth. He, and eventually others too, are convinced that he really is Olham. He has no memories of being anyone else, nor is there anyone else who has Olham’s memories. A Lockean theory (at least if not heavily qualified in ways that Locke’s followers have explored) would seem to entail that he is Olham. And yet he is not. (I put to one side the question of whether a robotic duplicate could in the first place really be said to think or have even pseudo-memories the way we might – I think a robot could not, in fact, be said literally to do so – but that is irrelevant to the present point.)

You might say that what the two stories illustrate is that, contrary to the implications of Locke’s theory, you are not (without qualification, anyway) who you think you are. If Quail’s memories were wiped entirely, he would no longer think he is Quail; but he would be Quail. The Olham doppelgänger thinks he is Olham; yet in fact, he is not Olham. If the view implicit in Dick’s stories is correct, then who you really are can be different from who you think you are.

You might say that what the two stories illustrate is that, contrary to the implications of Locke’s theory, you are not (without qualification, anyway) who you think you are.

I think there is a sense in which this is correct. That might sound like an expression of skepticism, but it is not; quite the opposite. To see why not, consider a parallel example, that of pain and its relationship to behavior like wincing, crying out, etc. Pain and pain behavior are not the same thing, as can be seen from the fact that pain can exist in the absence of the behavior we usually associate with it, and the behavior can exist in the absence of the pain (as when someone is determined to pretend that he is in pain). Thus the behaviorist is incorrect to identify pain with dispositions to behavior of the sort in question. However, the relationship between pain and behavior is nevertheless not a contingent one, as the French philosopher Rene Descartes would suppose. As Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein pointed out, pain behavior is normatively associated with pain. Pain and behavior of the sort in question are associated with one another in the standard case, even if there are unusual cases in which they come apart.

The way a Scholastic philosopher like Thomas Aquinas might put this is to say that behavior of the sort in question (wincing, crying out, etc.) is a proper accident of pain. A proper accident is not part of the essence of a thing but nevertheless flows from its essence – the stock example being the capacity for laughter, which is not part of the essence of man as a rational animal, but nevertheless flows from rational animality. Because a proper accident or property flows from the essence, things that have the essence tend to exhibit the proper accident (so that most people laugh from time to time, most dogs have four legs, etc.). But because the proper accidents or properties are distinct from the essence from which they flow, they might fail to manifest themselves if the flow is “blocked” (so that there are occasionally people who rarely if ever laugh, dogs which are missing a leg, etc.). Hence pain behavior in the normal case flows from pain in such a way that the connection between them is not merely contingent, but there can nevertheless be cases where such behavior does not manifest itself. (For discussion and defense of this approach to essence and properties, see my book Scholastic Metaphysics, especially chapter 4.)

Now, in the same way, you might say that memory is something like a proper accident of personal identity (though this would have to be tightened up in a more technical presentation, since accidents are, properly speaking, accidents of substances). That is to say, in the ordinary case, B’s being the same person as an earlier person A is associated with B’s remembering doing the things A did. The connection between memory and identity, as Locke rightly sees, is not merely contingent. Still, there can be cases where the “right” memories don’t manifest themselves even though personal identity is preserved, and this is what a Lockean account misses. Just as behaviorism mistakenly identifies pain with what is really only a proper accident of pain (i.e., pain behavior), so too does Locke identify personal identity with what is really only something like a proper accident of personal identity (i.e., memory).

As to skepticism: Suppose the behaviorist argued that by identifying pain with pain behavior and other mental states with other sorts of behavior, he was solving the problem of skepticism vis-à-vis the existence of other minds. You could never doubt whether another person is in pain, or thinking about the weather, or what have you; as long as pain behavior is present, pain itself is present, since pain just is the behavior. But this would, of course, “solve” the problem of skepticism vis-à-vis other minds only by stripping pain and other mental states of what is essential to them.

Or, to take yet another example, consider Irish philosopher George Berkeley’s claim that his idealism (the view that nothing exists except minds and their ideas) undermines skepticism about the existence of physical objects. The skeptic says that it might be, for all we know, that there is no table there even if we all have perceptual experiences of seeing the table, feeling it, etc. Berkeley responds that since the table just is (he claims) the collection of our perceptions of it, there can be no doubt that the table is there as long as the perceptions are there. This “solves” the problem of skepticism about the existence of physical objects only by stripping physical objects of the mind-independent ontological status usually thought essential to them.

Similarly, in assimilating personal identity to memory, Locke is, in effect, doing something parallel to the behaviorist’s assimilation of pain to pain behavior or Berkeley’s assimilation of physical objects to our perceptions of them. And the purported response to skepticism afforded by the assimilation is as bogus in this case as it is in the others. At first glance, it might seem that if you are, without qualification, whoever you think you are – whoever you seem to remember yourself being – then skepticism about personal identity is ruled out. If B seems to remember doing what A did, then B is the same person as A, and that is that; there would be no gap between memory and identity for the skeptic to exploit. But that would make the Martian impostor identical to the real Olham, and it would mean that the Quail who results from a complete memory wipe and replacement would not really be identical to Quail – consequences that are as extreme and implausible as the behaviorist’s identification of pain with pain behavior and Berkeley’s identification of physical objects with our perceptions of them.

The Scholastic distinction between essence and properties allows for a more nuanced and plausible account of the relationship between personal identity and memory – a consideration which might be taken to be a further argument for that distinction.

This article originally appeared at https://edwardfeser.blogspot.com