Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

8 min read

The Torah doesn’t use Pharaoh's actual name. Who was he?

I always had the impression that the Pharaoh of the Exodus was Ramses II, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. Do Jewish texts shed any light on his identity?

The Torah uses the generic title “pharaoh” when referring to the various Egyptian kings who ruled during the period of Israel’s enslavement and subsequent exodus. It never mentions their actual names. Variations of the name, “Ramses,” do appear in the Torah as the name of a place—or a number of places—indicating the locations Jews settled and worked during their time in the region.

For example, Genesis 47:11, mentions Ramses (רעמסס) as the area Joseph set aside for his father, Jacob, and brothers to live following their arrival in Egypt. Exodus 1:11 mentions Ramses, along with Pithom (פתם), as the cities Pharaoh ordered his Israelite slaves to build.

According to Kenneth Kitchen, a noted Egyptologist and scholar, the biblical “Ramses” is an almost exact transliteration of its Egyptian counterpart, and is the same as the name 11 Egyptian kings from the 19th and 20th Dynasties (about 1290-1070 BCE) used.

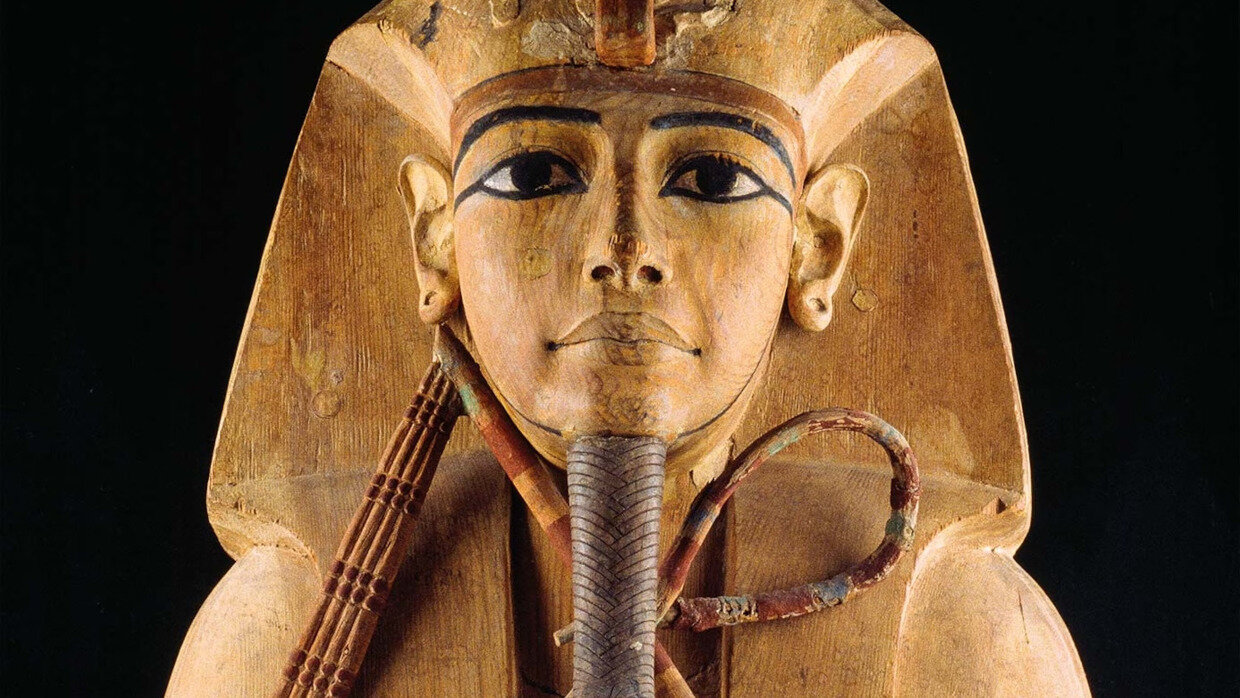

“The first of these, Ramses I, reigned only 16 months and built no cities. None of the rest founded major cities either, with but one exception. He was Ramses II, grandson of I, who was the builder of the vast city Pi-Ramesse A-nakhtu, ‘Domain of Ramses II, Great in Victory,’ suitably abbreviated to the distinctive and essential element ‘Ramses’ in Hebrew.”1

The Torah is familiar with the name, “Ramses.” Does that also indicate the identity of its leading villain?

According to Joshua Berman, a professor at Bar Ilan University and an important biblical scholar, the details the Torah recounts while chronicling the Exodus demonstrate a striking familiarity with the idiosyncrasies and realities of late-second-millennium Egypt, the likely time of the event. In particular, he notes that the Kadesh Poem—an Egyptian propagandist work that lauds the victory of Ramses II over the Hittites at Kadesh in what is believed to be the largest chariot battle in history—is very similar to the Song at the Sea (Exodus 15), and that the Torah ”appropriates far more than individual phrases and symbols … it adopts and adapts one of the best-known accounts of one of the greatest of all Egyptian pharaohs.”

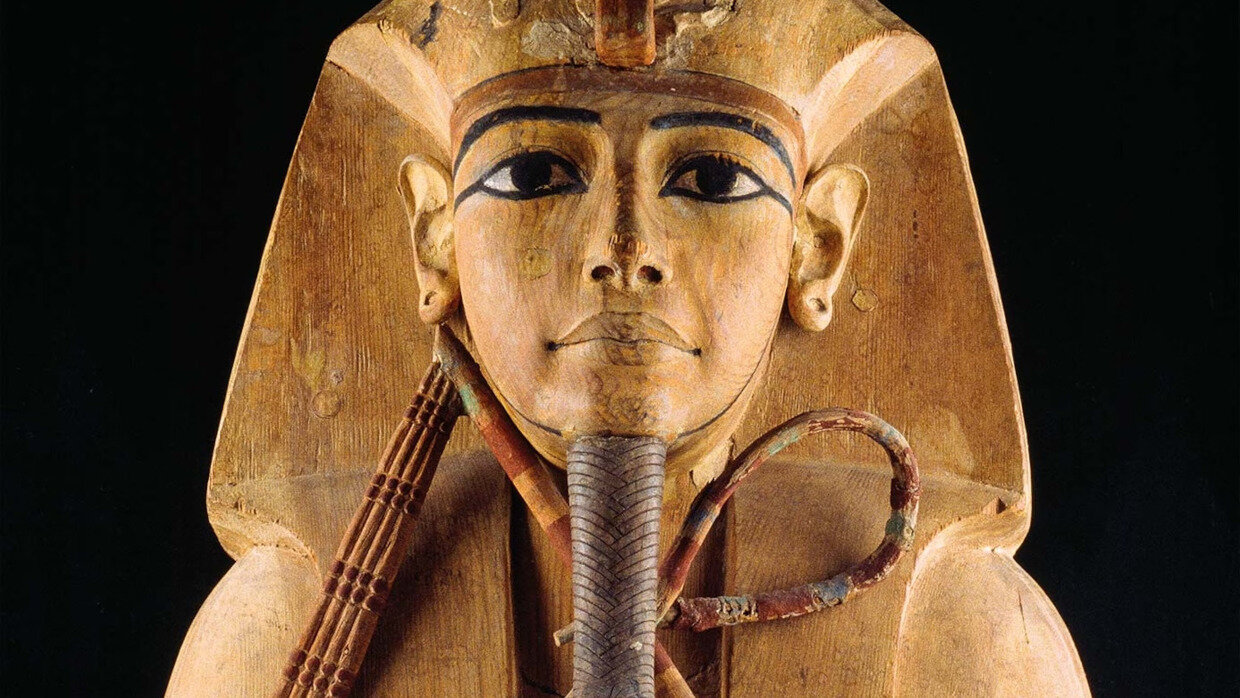

Statue of Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II in southern Egypt

Statue of Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II in southern Egypt

That appropriation, according to Berman, could only have been contemporaneous, indicating, possibly, that the Pharaoh of the Exodus was indeed Ramses II (Ramses the Great).

“The evidence adduced here can be reasonably taken as indicating that the poem was transmitted during the period of its greatest diffusion, which is the only period when anyone in Egypt seems to have paid much attention to it: namely, during the reign of Ramses II himself. In appropriating and ‘transvaluing’ the well-known composition of the Kadesh Poem of Ramses II, the Torah puts forward the claim that the God of Israel had far outdone the greatest achievement of the greatest earthly potentate.”2

Similar to Berman, Kitchen (as mentioned above), doesn’t explicitly claim that Ramses II was the pharaoh of the biblical Exodus, although based on the vast amount of evidence he presents—like verifying the existence and location of the cities the Torah mentions, showing the coastal Mediterranean settlements that the Torah claims forced the escaping Israelites to flee via a circuitous route, giving contemporaneous examples of other groups who fled en masse as a response to excessive or unfair policies or abuse, and more—that seems to be his best guess as well.

While Ramses II is a good candidate, the dates that he ruled, 1279-1213 BCE, are problematic. According to Jewish tradition—based on the second century work, Seder Olam Rabbah, attributed to the sage, Rabbi Yosef ben Halafta—the Egyptian Exodus took place in 1312 BCE, at least a decade before Ramses II was born.

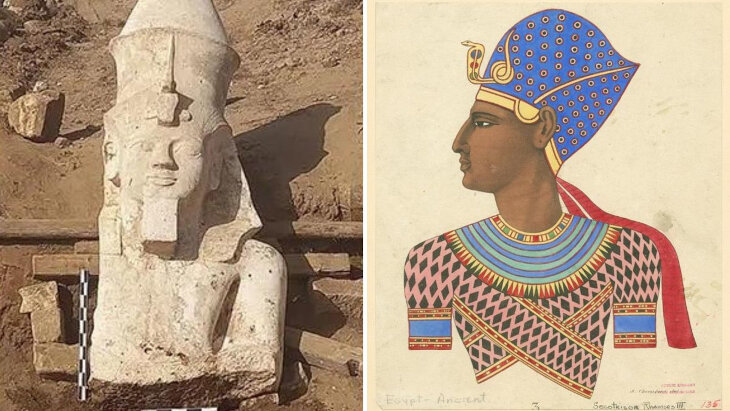

Based on that chronology, the Exodus would have taken place during the reign of the pharaoh, Horemheb (ruled 1317-1290), with the destruction wrought by the Exodus, possibly, bringing about the end of the 18th dynasty.

The traditional dates are disputed, however, and many scholars consider them to be off by about 165 years. Based on that understanding, the Exodus would have been 165 years earlier (in 1477 BCE), during the reign of the powerful Thutmose III, which, according to some, could explain the apparent rise of a type of monotheism during the reign of Akhenaten a century later.3

Another theory, advanced by the Egyptologist David Rohl, involves reworking the biblical timeline in relation to Egypt. Rohl moves the Exodus back to 1650 BCE to coincide with the reign of the undistinguished, and relatively unknown pharaoh, Dudimose II.

The strength of Rohl’s argument is that a) Dudimose, as a weak and ineffectual leader, is the type of ruler you’d expect to see at a time of national calamity, and b) Dudimose, according to Rohl, was the last pharaoh of the 13th dynasty; followed by the Hyksos invasion, and almost a century of foreign rule in Egypt.4 However, Rohl’s theory is controversial, and hasn’t won much support in academic circles.

According to the Torah (Exodus 2), despite a decree calling for the death of newborn Jewish boys, Moses survived. Pharaoh’s daughter rescued him, named him Moses (משה), and raised him as her own. In popular culture—thanks to the Cecil B. DeMille’s film, the Ten Commandments—Moses is portrayed as growing up as an Egyptian prince, and rivaling his contemporary, the next Egyptian pharaoh. The Torah’s narrative is less dramatic, although it does recount that as a young man, Moses kills an Egyptian taskmaster, which is the plot twist that forced his eventual exile.

Decades later, Moses returned to Egypt at God’s command, confronted Pharaoh, and ultimately led the Jewish people to freedom. His request, to be granted time off for a religious holiday, was consistent with the types of requests granted to slaves at the time. Throughout the episode of the Ten Plagues (Exodus, chapters 7-12), Moses’s interactions with Pharaoh are designed to disabuse Pharaoh of the belief that he was divine, and to demonstrate that God is the only power.

For example, in Exodus 7:15, Moses is commanded to confront Pharaoh on the banks of the Nile, when he “goes out to the water,” indicating Pharaoh’s most human moment, when he’s relieving himself, and, obviously, not a god;5 or Exodus 10:16, when Pharaoh confesses his terror following the plague of locusts.

The Pharaoh who was asked to release the Hebrews is unknown, as the Torah only uses the title, “pharaoh,” but doesn’t mention his actual name. Amongst scholars, Ramses II, for a variety of reasons, seems to be the best guest. Traditional Jewish sources, in general, don’t address the issue.

Scholars offer a range of opinions as to the identity of the biblical pharaoh. At least four pharaohs are mentioned in the Torah: the pharaoh at the time of Abraham, the pharaoh who appointed Joseph to a position of power, the first pharaoh to issue anti-Jewish decrees, and the pharaoh of the Exodus. According to Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, in his commentary to the Living Torah, those pharaohs could be (depending on the dating system used) an unknown pharaoh of the second intermediate period or Amenemhet II; Amenhotep I or Ahmose; Thutmose IV or an unknown pharaoh during the reign of the Hyksos; and Horemheb or Thutmose III; although, as noted above, the evidence is not conclusive, and other possibilities should also be considered.

According to Jewish tradition, despite a decree calling for the death of newborn Jewish boys, Moses survived. Pharaoh’s daughter rescued him, named him Moses, and raised him as her own. The Torah gives no indication that Pharaoh had any involvement in Moses’s upbringing, although a number of rabbinical sources seem to say otherwise. In any event, the reigning pharaoh at the time of Moses’s birth was not his nemesis at the time of the Exodus, and, most likely, would have been whoever preceded him. In the days of Ramses II that would have been Seti I; Horemheb’s predecessor was Ay; before Thutmose III was Thutmose II; and the history around Dudimose is unclear.

I cant remember where but there was a dating of about 200years before accepted date. The reason was because of the writing and how it was done. They found a cave in the desert that the writing matched the time period they were talking about and it refered to the Exodus. It was really good and was the most substance filled I have seen.

This study is quite informative and a reasonable explanation of the Pharaoh of the time of the Exodus. https://youtu.be/2JusQxiTXnE?si=Zf1TlfttNd7J0Se7

Does it matter “when” it happened that the Hebrews were taken out of Egypt by Moses according to the bible? This is the reason why we celebrate Pesach, we celebrate our freedom as we have done so for many,many years.

Timothy Mahoney did 2 documentaries that have an interesting perspective on dating Joseph, Moses, the Exodus, and Joshua's conquest of Canaan.

"Patterns of Evidence: the Exodus" &

"Patterns of Evidence: The Moses Controversy"

Timothy Mahoney interviews multiple people from different perspectives, religious, non-religious, archeologist etc. His perspective leans towards it did happen but his theory is the Dating of the events are alittle off and the whole timeline of Egypt may need to be adjusted.

Also, the main argument that the Exodus didn't happen is that it is generally accepted that Rameses II is the Pharoah during Moses because of the city named Rameses that is named in Exodus 1. The city Ramases is built on Avaris & the name updated when Exodus text was finalized.

If we carbon date pithom and Rameses wouldn't that help? We have their locations. Also wouldn't it make more sense for Akhenaten to be the Pharaoh of Joseph considering what he saw?

The theory I learned is that the Pharaoh who welcomed Jacob was a Hyksos Pharaoh and the one who “didn’t know” Joseph was the reinstated native dynastic Pharaoh. That would accord with the later dating of the story.

I don't think this quite lines up when we consider The common date of Solomon's Temple and Moses crossing the Red Sea 480 years prior. Also if the Traditional Site of Jericho is assumed the be the actual Jericho from the Bible due to the Archeological evidence that the city was wiped out suddenly in the spring, there was intense fire and the walls fell outward; all evidence that supports the Biblical Account, then again this doesn't make sense either. The city was destroyed much earlier During Egypt's Middle Kingdom.

You are probably correct; the idea behind the theory that I learned is that an “outsider” Pharaoh would be more likely to welcome other outsiders and a “native” Pharaoh more likely to resent them. Only one of many theories as this article shows.