Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

5 min read

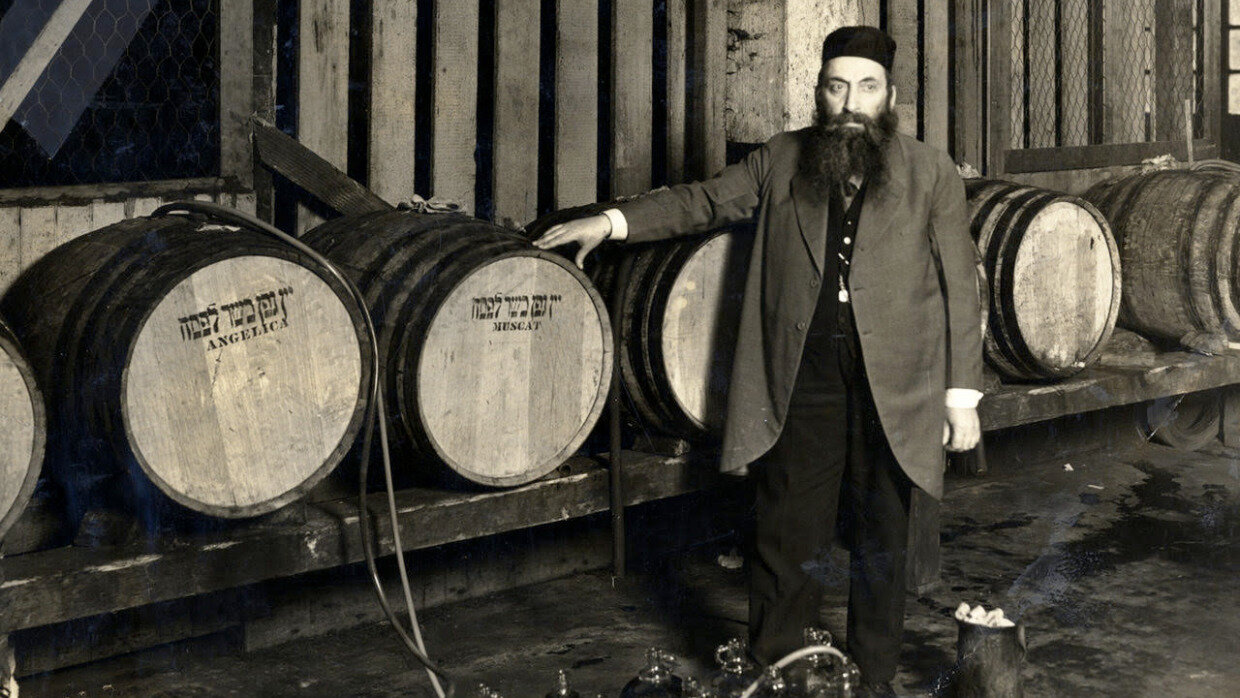

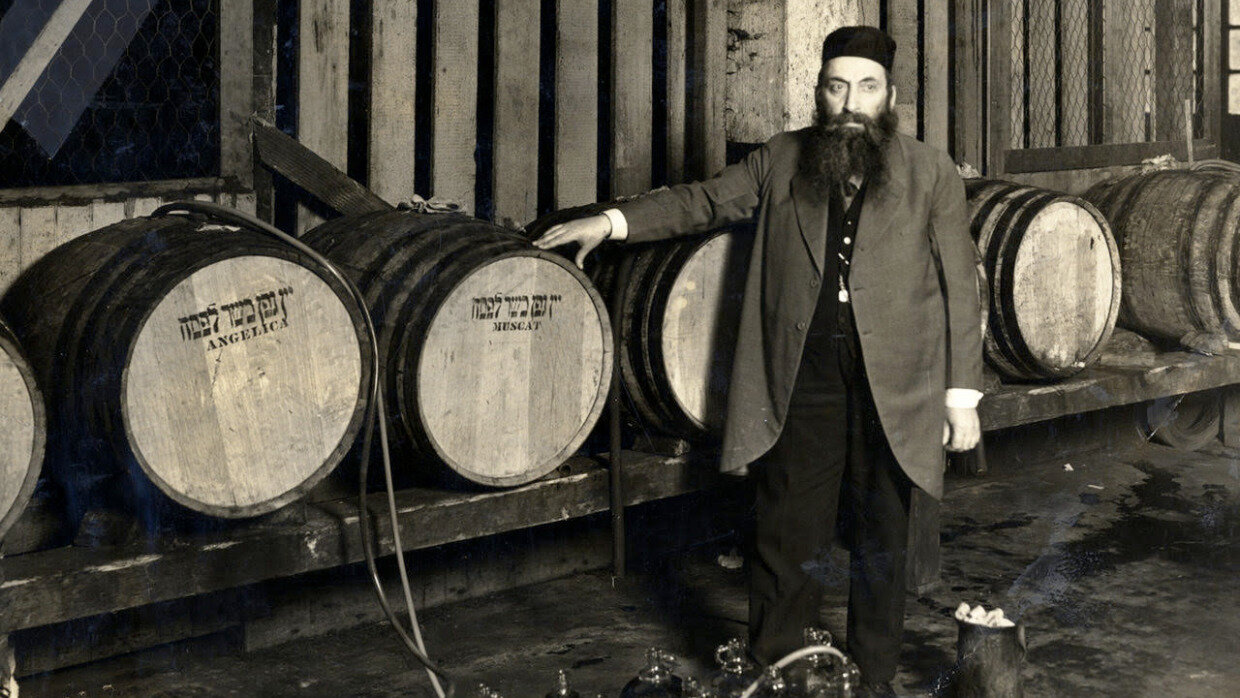

The Prohibition Act made acquiring wine for the four cups quite the hassle.

What did American Jews during the Prohibition do on Passover when getting wine was almost impossible?

Ratified in 1920, the 18th Amendment prohibited the “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors… for beverage purposes.” From this, Congress enacted the National Prohibition Act—aka the Volstead Act — to implement the amendment’s prohibitions.

At first Jewish practices weren’t affected too much. Due to the 1st Amendment guarantee of religious freedom, exceptions were made for religious reasons. But unlike Catholic mass and communion which are only done in the Church, Jewish rituals like kiddush and havadala (both performed over wine) primarily take place in the home, outside of public view. This meant that consumption of wine could continue uninhibited, allowing for the opportunity to violate the “for beverage purposes” part of the law without consequence – possibly to excess and inebriation. Imagine authorities stumbling upon a Purim celebration!

Though rituals may have continued, the Prohibition Act made acquiring the wine quite the hassle. The government allowed a limited amount of wine per family per year for “non-intoxicating” consumption so Jews could continue performing rituals like kiddush, the seven blessings for a wedding, and of course the four cups of wine for Passover. Commercial wine was still produced, but required a special license along with complicated bureaucracy for distribution. Those beverages were delivered directly to the rabbi of a synagogue, which he then distributed to his congregants. He had to estimate the needs of his community and order accordingly, paying upfront. If he estimated too little, families would be without wine. If he estimated too much, the congregation would have to pay for the excesses out of pocket.

Not surprisingly, there was abuse in the system. There were reports of some congregations over-reporting their member size by as much as tenfold. Other fraudsters applied for the exception by using the name of a closed or non-existent congregation. It was difficult to confirm the authenticity of a rabbi, meaning that applying for the exception was easier than other religions. This led to the term “wine rabbis.” Many Jews were infuriated with the fraud and petitioned for change. This, along with other abuses (organized crime, black market sales, etc.), led to crackdowns.

The California Legislature passed regulations specifically targeting Jews who flouted the law. Federal measures tightened and wine shipments practically dried up. Commercial manufacturers couldn’t meet demand in high population areas such as New York.

Some families just used grape juice, but at the time, grape juice wasn’t widely available as it is today. Prior to the start of the Welch’s Grape Juice Co. in 1893, unfermented grape juice wasn’t sold shelf-stable and commercially. During the prohibition, small quantities of Welch’s were available. Kosher certification for both grape juice and wine is complicated and Kosher production of grape juice hadn’t been set up the way it had been for wine.

Observant Jews were reluctant to use grape juice for kiddush and the four cups. Some grape juice was too diluted with water to be considered as “fruit of the vine.” Although one could use freshly squeezed grape juice according to Jewish law, authorities ruled that “it is preferable or optimal to use aged wine for Kiddush, at least 40 days old.” For Passover, a time when many Jews are particularly careful and stringent with their fulfillment of the holiday’s commandments, many Jews desired to fulfill the mitzvah to drink four cups of wine in the most ideal fashion – and that required wine.

How did they manage? Families were able to still acquire the required four cups of wine for a Seder. But that would use up their entire allotment for the year. Other rituals? Forget it. Some made their limited supply stretch by diluting the wine with water just enough to satisfy Torah law. Others resorted to making wine at home (which was legally permitted to a limited degree) using grapes or even raisins. Though Prohibition created severe hardships for those trying to celebrate Passover and other holidays in the most stringent way, the worst of these restrictions only came in the Volstead Act’s final years. So the worst of problems only had to be endured for a relatively short period.

Prohibition ended in 1933, when the ratification of the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th Amendment. With the years of scarcity, the pent-up demand led to a thriving new industry. The Monarch Wine company made a deal with the Manischewitz food company to produce wine from the concord grape, which would become an industry leader in kosher wine.

Their slogan “Wine like mother used to make” directly invoked the homebrewed necessity brought on by Prohibition.

Today, many roll their eyes at the sight of the overly-sweet and syrupy brand. But 100 years ago, Jews would have paid the highest of prices for just four cups to complete their Seder!

Featured image: Rabbi Mayer Hirsch with barrels of sacramental kosher wine during Prohibition in San Francisco, ca. 1930. (The Magnes Collection)