Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

10 min read

As a teen, Adolfo Kaminsky forged passports to help children flee the Nazis. The Holocaust hero recently passed away at age 97.

Adolfo Kaminsky’s life mirrored many of the upheavals in Jewish history in the 20th century. His parents were Jews from Russia: his mother Anna fled to Argentina to escape pogroms in the early 1900s. Adolfo’s father Salomon was posted in Buenos Aires by a Communist Jewish newspaper. He and Anna met and started their family in Argentina; Adolfo, their youngest son, was born there in 1925.

In the early 1930s, the family moved to the town of Vire in the northern French region of Normandy. They were desperately poor, and Adolfo left school at 13 to go to work. He spent time in various jobs, then finally found a job that he greatly enjoyed, working for a clothing dyer. He enjoyed the chemistry aspect of his job so much that he took a second job working as an assistant to a chemist in a dairy. The lessons he learned there would help him later on in his new life as a resistance fighter, once World War II broke out.

In 1940, Germany invaded France. Adolfo and his family, like all Jews, were forced to register with the local authorities. The following year, in August 1941, the Nazis set up a concentration camp just outside Paris in the suburb of Drancy. The first contingent of Jews sent there were 4,200 Jewish men who were arrested in Paris. Soon, Jews from throughout occupied France were being transferred to Drancy.

Staffed by French police officers, Drancy was a holding area for Jews before they were deported to Auschwitz. Built to hold 700 prisoners, it held ten times that number at its peak. The conditions inside Drancy were dreadful. Many people died of disease and mistreatment. Young children were torn from their parents upon entering the camp.

Adolfo and his family were sent to Drancy in 1941. “I knew what awaited those who were going to be deported,” he later recalled. As Argentinian citizens, Adolfo’s brothers hoped that they might be spared, and one of his brothers wrote desperate letters to the Argentinian consulate while they were imprisoned. As Argentinians, they were allowed to send out letters, a right denied to some other prisoners. Finally, the Argentinian authorities intervened and Adolfo, his two older brothers and his parents were freed.

“We were still in danger,” Adolfo later recalled. “We had to disappear.”

His father contacted a member of a French Resistance movement, requesting help in gaining false documents in order to hide their Jewish identities. His father sent Adolfo, then 16 years old, to meet with a Resistance contact. “I met with a little man nicknamed Penguin,” Adolfo remembered. “He told me, ‘I’ll put you down as a student’.” Adolfo explained that he had to go out to work, and the Resistance official asked him what his job was. “Clothes dyer,” Adolfo replied.

It was a turning point that would save not only Adolfo’s life but the lives of thousands of others. The Resistance member looked at Adolfo and asked, “Clothes dyer? Do you know how to remove ink stains?” Adolfo answered yes and was recruited to help fight.

He joined an elite Resistance unit nicknamed “La Sixieme,” which altered official documents. Adolfo’s entire life had prepared him for this point. In school, he’d worked on the school paper, and knew about fonts and creating official-looking writing. At the clothes dyer he’d learned how to dissolve ink. And his job at the dairy taught him that lactic acid - contained in milk - could dissolve ink, including the Waterman’s blue “indelible” ink, which was used on French ID cards.

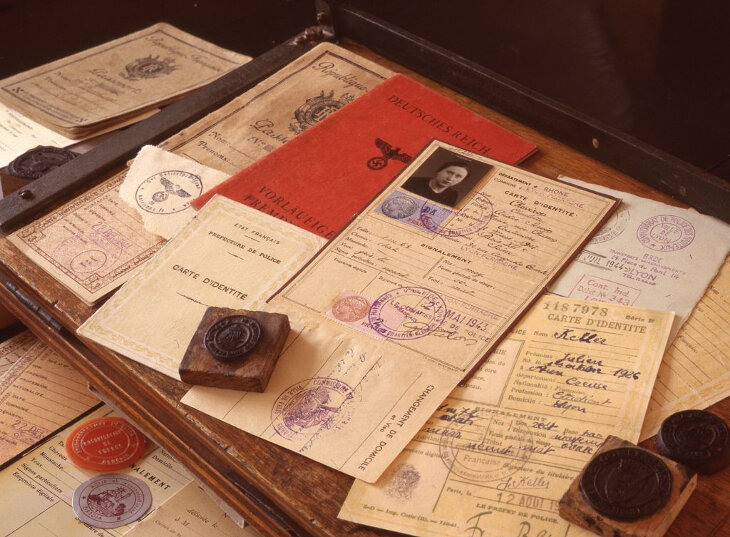

Documents forged by Adolfo Kaminsky

Documents forged by Adolfo Kaminsky

Adolfo wasn’t used to breaking the law, and he never forgot the moment he did so to create his very first forged document: his own. He created a false ID card naming him as Julien Adolphe Keller, born in Alsace. He also created a forged passport, baptism certificate and birth certificate to cement his new identity. It was a pattern he would repeat over and over again, thousands of times, creating entirely new identities for French Jews to help them hide and escape from France.

In the beginning of 1942, the Wannsee Conference decided the fate of Europe’s Jews: the wholescale murder of every single Jewish man, woman, and child was adopted as official Nazi policy, applicable in all lands the Nazis held. In France, the effect was immediate. Jews were rounded up and deported to Auschwitz in large groups. On July 16 and 17, 1942, French police arrested 13,000 Jews in Paris and sent them to the Velodrome d’Hiver bicycle track, where they were imprisoned in the summer heat for several days without food or water. The survivors were sent to Auschwitz. By the end of 1942, 42,000 French Jews had been deported through the Drancy concentration camp.

One round up of French Jews in particular tore Adolfo’s world apart: his mother Anna received word of a mass arrest of Jews and traveled to Paris to warn one of Adolfo’s brothers that he risked arrest. Anna was killed on a train as she returned home. After that, Adolfo threw himself even more into his work.

“As a cover, we disguised ourselves as painters,” he later related. It was an ideal way to explain away the smell of chemicals that permeated the apartment where Adolfo and his colleagues worked. The story satisfied their neighbors. “Same for the inspector who came to read the electricity meter: each time he came into our laboratory, he complimented us on our paintings.” Adolfo built equipment to age documents out of common household items such as a pipe and a bicycle wheel. “We made identity cards, ration cards, tobacco cards, baptism certificates, marriage certificates, birth certificates…. They don't know who saved them. I was a stranger,” he later described in a documentary his daughter Sarah helped The New York Times make about his life.

Word got around that a master forger was working in Paris. French police and Nazi officials were charged with finding the fugitive at all costs. One day, police officers entered a Paris Metro train Adolfo was traveling in, searching for the forger. They moved down the aisle, shouting “Identity check! General search!” They stopped in front of Adolfo and demanded to know what was inside his satchel.

It contained the forgery materials they were searching for: rubber stamps, pens, a stapler, and 50 blank identity cards. Adolfo, a slight teenager at the time, looked up at the officers and bluffed. “Sandwiches,” he answered, offering his bag. “Would you like to see one?” The police officers shook their heads and moved on; it never occurred to them that a mere kid was the forger they were looking for.

Adolfo was so successful that his Resistance cell became a magnet for requests for false documents to help Jews evade arrest from all over France, primarily children. One day, Adolfo and his colleagues received an impossible-sounding request: one Resistance group wanted to smuggle 300 Jewish children into Switzerland or other safe destinations. They wanted Adolfo to create 300 birth certificates, 300 baptism certificates, and 300 ration cards. He had three days to complete the task.

Adolfo with his daughter Sarah

Adolfo with his daughter Sarah

“My biggest fear was making a technical mistake, a little detail that might escape me,” Adolfo explained. “On every document rests the life or death of a human being. So I worked, worked, worked, until I passed out. When I woke up, I kept working. We couldn’t stop… In one hour I can make 30 blank documents. If I sleep for an hour, 30 people will die.”

He finished the assignment just in the nick of time. This grueling schedule took a toll. After years of painstaking work, Adolfo lost the sight in one eye. He estimated that he created documents for 14,000 Jews, the majority of them children.

Adolfo’s work as a forger did not end with the conclusion of World War II. Already in 1944, Jewish partisans from the Land of Israel began to plan to help Jews who’d survived the Holocaust set sail for Europe and travel to Mandatory Palestine. “Bricha” means escape in Hebrew, and was the name given to the audacious, top-secret plan to smuggle desperate Holocaust survivors to the Land of Israel.

The British controlled the Land of Israel at the time, and opposed any Jewish immigration. Nevertheless, after the Holocaust, nearly a quarter of a million Jewish survivors gathered in Displaced Persons Camps in Germany, Austria, and Italy, with the goal of traveling to ports along the Mediterranean and boarding ships that would take them to the Land of Israel, or Mandatory Palestine as it was called at the time. Thousands of Jews managed to move to the south of Italy, where they awaited Bricha ships that would try and outrun the British blockade and make it to the port of Haifa.

Adolfo created false papers for Jews seeking to immigrate to Palestine. He later moved to Israel and worked as a forger for the Irgun, the Jewish underground movement which fought for Jewish independence from British rule.

Adolfo went on to work as a forger for various radical political movements around the world, including in Algeria, where he lived for a time, and in Latin America. He never told his family about his political work. From the 1970s onward, he began working as an artistic photographer, capturing cityscapes and other images of beauty in France. However, he remained haunted by the Holocaust and the loss of so many of his friends and relatives and his fellow Resistance members during the Holocaust. Many of his friends from the French Resistance who’d survived died by suicide after the war.

“I remember one day: I knocked on all the doors on a list that I received the day before and spent all night learning by heart,” he later explained. “The names and addresses of dozens of Jewish families that would be rounded up the next day at dawn. I remember a widow on Oberkampf Street. Her name was Madam Drawda. When I offered to make her documents she got offended: ‘Why should I hide? I haven’t done anything, and I’ve been French for many generations.’ I tried everything to convince her. I knew if she stayed she and her children would be deported and sent to die.”

She - as well as her children - likely perished.

“I continued to fight. I think that’s what saved me,” Adolfo explained. By aiding resistance groups all over the world, he was able to feel that he continued to help others and make a difference.

Adolfo married Jeanine Korngold in 1952; they divorced soon after. He married again decades later. He passed away on January 9, 2023, and is survived by his wife and four children, as well as nine grandchildren. “I’ve had a very happy life with an adorable wife, with children,” he explained in a 2017 documentary about his life. “It’s truly something to be proud of. But there are so many corpses. If I hadn't been able to do anything, I wouldn’t have been able to bear it.”

Featured Image: Steven Wassenaar