Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

6 min read

Two divergent views on the causality of the Holocaust and the driving forces of history.

Scholars are divided regarding the causality of the Holocaust.

American historian Christopher Browning explains that, “If one looks at the Armenian genocide, there’s no prominent Turkish leader. If one looks at the Rwanda genocide, there’s no prominent Hutu leader… In the case of the Holocaust… clearly Hitler is the dominant key figure… but I don’t think we could say that such things are impossible without a figure like Hitler, because in too many cases we’ve seen that genocide can happen even without a dominant dictator.”

On the other hand, Milton Himmelfarb, a respected sociologist, argued in Commentary Magazine that while every individual is responsible for his or her own actions, without Hitler, history would have been vastly different. Himmelfarb’s proof? Hitler had many options to choose from. If, instead of murder, he had ordered the immediate expulsion of all Jews from all conquered territories, there would have been no ovens.

As Himmelfarb put it, “The obedience of… the SS was to Hitler, not to anti-Semitism.” Without him, there may well have been oppression, expulsion, persecution and even death – but, using the phrase introduced by Canadian historian Michael Marrus: No Hitler, no Holocaust.

Do leaders make history, or is history the result of societal trends?

Similarly, German Professor Eberhard Jäckel opines that “[Hitler] was the driving force. Of course… he needed collaborators… But… the role of Hitler was central.”

I recently asked Professor Yehuda Bauer, Professor Emeritus of Holocaust Studies at Hebrew University, recipient of the Israel Prize and considered by many the preeminent scholar of the Holocaust, for his thoughts on the subject. He responded, “My own view is that Hitler was the accepted oracle of his movement, and was convinced that Soviet Bolshevism is Jewish and its only purpose is to have International Jewry rule the world (see his memo to Goering of August 1936). Hence the need for Germany to start a war. His role in pushing Nazi Germany into the war, basically because of radical antisemitism, was central. Of course, without support from the Nazi leadership he could not have pushed for policies that developed, and ultimately resulted in the genocide of the Jews. Hence his role is central, but the support he had was a necessary accompaniment.”

What about the significant Nazi leadership? The thousands of commanders and soldiers who voluntarily committed atrocities? What about the Nazi collaborators in Poland, the Ukraine, and elsewhere? They didn’t need to murder Jews – indeed many of their compatriots did not, and a minority even protected them. Why blame only Hitler?

Causality and blame are not synonymous. Blame is individual, causality is global. Every individual German soldier is to blame for his or her role in the Holocaust, but cannot be said to have “caused” the historic tragedy. Regarding causality, however, the experts are divided, as we’ve seen, and there may be no definitive answer.

This question is related to a larger one: do leaders make history, or is history the result of societal trends?

Despite his many racist and antisemitic statements, Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) is widely considered one of Scotland’s great thinkers. He is best known for what he called the “Great Man Theory of History”: “The history of the world is nothing but the biography of great men.” For Carlyle, movements and historical trends are far less important than the actions of individual leaders. Leaders make history.

Compare his view to the “History from Below” approach which sees any individual – including leaders – as largely inconsequential. First described by French historian Lucien Febrve in 1932 ("histoire vue d'en bas et non d'en haut" – “history seen from below not above”) and championed by Marxist historians, this “History from Below” approach believes general trends and movements dictate events; leaders simply ride the wave of history.

Or, as Herbert Spencer put it, leaders are merely reflections of their environment.

A possible example of this phenomenon is the Russian Revolution: The “History from Below” approach would explain that due to various economic, social and religious factors, a significant revolution of some kind was due to happen - with or without Lenin.

Carlyle’s “Great Man” Theory seems to be gaining ground. It is hard to imagine Russia bombing Kiev and scorching the Ukraine without Vladimir Putin at the helm, and hard to imagine Ukraine responding as steadfastly and effectively as it has without Volodymyr Zelensky in charge. Still, the truth may well lie somewhere in between the two views.

My recent conversation with Rabbi Shmuel Lynn, the director of Olami Manhattan, a popular educational and social center for Jewish young professionals in Greenwich Village, NY, sheds some light on what can we learn from these divergent views. Rabbi Lynn is a pioneer in informal Holocaust education who has led dozens of groups to Poland. He explained that the “History from Below” approach shows how the masses have a certain power that individuals do not. Any individual, even a leader, is limited in his or her influence. We can only really affect change by coming together.

The “Great Man Theory of History” teaches that people need leaders to unite and inspire them. The Jewish community, for example, must invest in developing the next generation of leadership, because leaders are consequential.

"If one man can kill six million Jews, then one man can save six million Jews."

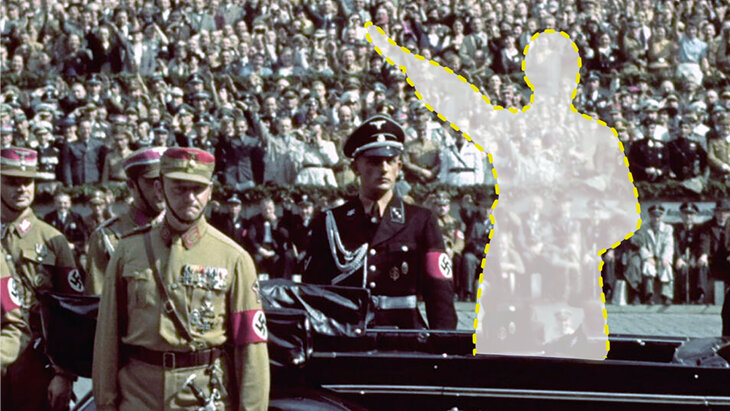

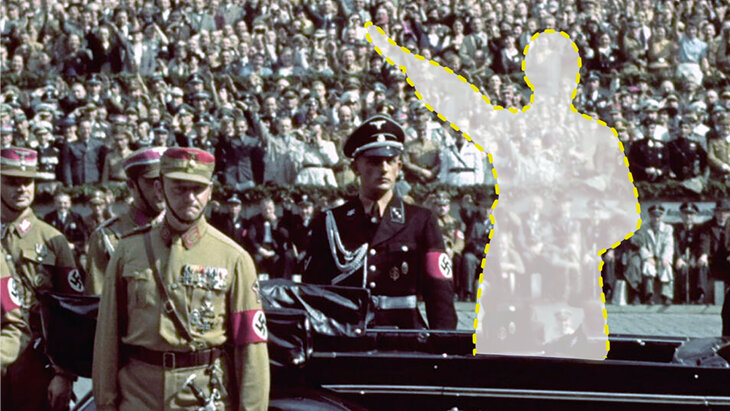

The “Great Man Theory of History” also highlights the tremendous impact an individual can make on the world – for good and for evil. A striking photo at the Aish HaTorah World Center brings home this point. There is a framed photo of Rabbi Elazar Menachem Man Shach (1899 - 2001), one of the greatest rabbis in the 20th century, visiting Aish HaTorah for the bris of Rabbi Noah Weinberg’s son, many decades ago.

Rabbi Shach was moved by the large number of students at Aish who had no previous background in Jewish learning and observance. He saw firsthand the impact Rabbi Weinberg was having in creating an outreach movement, which was then at its early stages. Rabbi Shach told the students, "If one man can kill six million Jews, then one man can save six million Jews." No matter how powerful the forces of evil seem to be, the forces of good are always greater.

Therefore, if one man can bring so much evil to the world, imagine how much good one individual could bring to the world.