Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

8 min read

Eighty-two years after my mother’s hurried departure, my son and his family are moving to Berlin. I’m struggling to accept it.

Bubby closed the door to her home on Joste Strasse before rushing to the Hauptbahnhof train station in Berlin, not knowing when she and my mother would return. Their second-floor, comfortably furnished apartment had a fireplace in every room. It was graced with Meissen figurines, crystal wine goblets, an antique brass filigree clock they wound up once a week, a huge silver menorah with two lions, cups for oil on opposite ends, and eight smaller cups on the bottom. They never saw any of these things again.

On September 2, 1939, my mother and grandmother boarded a train to Cologne. Their plan? Rendezvous at Cologne’s Jewish Community Center with smugglers to guide them through the forest and over the border into Belgium. My grandfather was already in Antwerp, in an apartment set up with furniture he built out of scavenged wood scraps, waiting for them to join him. At 5:20 a.m. that morning, Germany invaded Poland, and all hope for a peaceful end to Hitler’s reign was dashed.

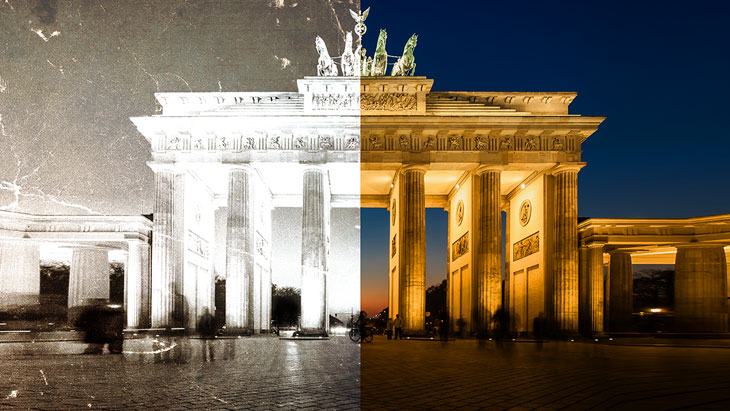

Before heading to the station, they stopped at the Ryke Strasse Synagogue. In better times, from the women’s balcony they’d see my grandfather praying below in his fourth-row seat, just right of center. Casting a longing, last glance, they continued on their way.

The Ryke Strasse Synagogue

The Ryke Strasse Synagogue

Mom was eleven years old. Their stuffed suitcases held only clothes and vital papers like her school records, birth certificate, and Bubby’s marriage certificate. Their first attempt to reach Belgian soil failed – the smuggler abandoned them in the middle of the forest. Though terrified, my mother kept her wits and guided them back to their starting point. The second attempt succeeded, and my mother and grandmother reunited with my grandfather in Antwerp.

Seven months later, Germany invaded Belgium and my grandfather, along with all Jewish men, were sent to camps in Nazi occupied Southern France. In 1942, he was deported to Auschwitz and perished. No longer safe in Antwerp, Bubby moved with Mom to Liege, 132 kilometers away. A few months later, a heroic Belgian couple hid them in an attic, where they remained until the war ended in 1945. Finally, their visas arrived in 1948, and they sailed off to the United States. They never spoke German again, preferring the language of their adopted country, where I was born.

Mom mastered English, speaking with barely a trace of her German roots. She never talked about my grandfather, what they’d endured, or how they survived. It was just too painful to remember, and talking triggered nightmares.

Thanks to my late mother’s forced departure from the land of her birth, my descendants and I qualify for German citizenship. “It’s an EU country,” my sons said, asking for my help. “There could be advantages to having an EU passport.” I wasn’t interested, but with the very documents Mom and Bubby had smuggled out, they proved our ties to Germany, and got citizenship and passports. This was a means to an end, I thought, a way to gain access to the EU and the free, high quality education so many EU countries offer.

I was stunned into silence. Moving to Berlin? They were clearly excited. All I could do was cry.

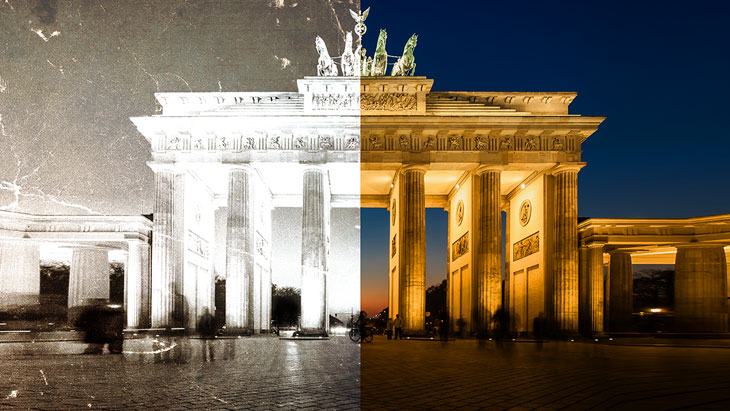

Then, last summer, my eldest son dropped a bomb. “We’re moving to Berlin!” he announced one Erev Shabbat after we’d put his young girls – my precious granddaughters – to sleep. Sitting on our couch, he and my daughter-in-law, an artist, gushed, “We’ve been thinking about this for a while… the arts community in Berlin is thriving, and we’ve decided to move there.”

What? I was stunned into silence, and could barely choke out a reply. Where was this coming from? What would happen to my twice or three-times-weekly contact with our grandkids? They were clearly excited. All I could do was cry.

Reading a story to my grandkids

Reading a story to my grandkids

My husband and I raised two sons far from the helping hands of our families. Not wishing to repeat that pattern, our mantra became, “Isn’t it great to be together?” Both sons settled in Seattle, a mere 10-minute drive from our home. We were constantly in and out of each other’s houses, sharing meals, hiking and biking together, going to museums and movies, gathering with them and their friends for parties in the park, genuinely enjoying each other’s company. From my point of view, life was blissfully good and couldn’t get much better. But their dreams, I’ve learned, are different from mine.

“Why can’t you be happy for us?” my daughter-in-law exclaimed with frustration, after a few weeks of what seemed like non-stop crying on my part. By then, my son had found a way to support the family and landed a job with a start-up in Berlin, which offers on-site daycare. Amazed that he’d pulled this off, and proud of his accomplishment, it was still hard for me to find any enthusiasm for their big adventure. It felt like an abandonment, and the idea of Germany stressed me – vestiges of transgenerational trauma. As a child, just hearing German spoken sent chills up my spine. Over the years, as Germany reconciled openly and honestly with its history, my views towards it, and the German people have softened. But my heart aches when I think of my granddaughters speaking a language that jangles my nerves.

“If you told me you were moving to New Jersey,” I told my kids, “it would be hard for me. But Germany? That adds an extra layer of pain,” I tried to explain.

If you told me you were moving to New Jersey, it would be hard for me. But Germany? That adds an extra layer of pain.

My sister told me bluntly, “Mommy would be turning over in her grave if she knew.” I wasn’t so sure. In the 1970s, Berlin’s municipal government began extending invitations to former citizens who’d fled Nazi persecution to return as guests of the city. Mom knew about this program for fifteen years before finally applying to participate. The offer of free airfare for her and my father, free hotel, meals, sight-seeing, musical performances, and more, left her cold. “I have no desire to go back to Germany,” she told me. She reluctantly applied after a chance meeting with a former classmate from Berlin who’d attended the program and endorsed it heartily. In 1997, the Governing Mayor of Berlin’s Senatskanzlei District formally issued an invitation for my parents to visit. Two hundred people were in their group, Jews who had settled in the US, Canada, Israel, England, Australia, Brazil, and Peru.

The visit was a huge success, and Mom shared every detail when she returned home. Joste Strasse, in the Eastern sector, was bombed during the war, and the whole square block where she grew up was destroyed. But the Ryke Strasse Synagogue survived. On Kristallnacht, Nazis set fire to the sanctuary. The fire department, fearing that adjoining residential buildings would go up in flames, stopped the mob from igniting the whole place. After the war, the magnificent sanctuary was restored to its former glory. Mom got to sit in the fourth row, right of center, in her late father’s chair. This was the highlight of her return to Berlin.

After this trip, my aging parents began chronicling their war-time experiences and sharing them with anyone who would listen. Churches, Rotary groups and schools invited them to speak, and they eagerly accepted to prevent their stories from following them to their graves.

Today, attracted by its vibrant culture, affordable apartments, and energy, 30,000 Jews call Berlin home despite persistent anti-Semitic attacks and constant police protection around Jewish sites. Covid-19 devasted the arts community in Seattle, shuttering theaters and permanently closing dance performance venues. Meanwhile, Berlin’s Culture Ministry gave €500 million in cash grants to artists and entrepreneurs, to preserve the richness and variety of Berlin’s cultural life. With free daycare, abundant playgrounds, and a monthly child benefit of €219 per dependent under 18, expats say it’s a great place to raise kids.

My beloved family and close friends

My beloved family and close friends

And so, 82 years after my mother’s hurried departure, we come full circle. My children are selling their house in Seattle to make Berlin their home. Our five-year-old granddaughter and her parents take German-language classes every week; the two-year-old will pick it up quickly in day care. Their excitement is growing, but mine is still on ice. Holding my grand-daughters’ tiny hands, I think of how I’ll miss their warm touch.

Last week my son asked, “Was Savta’s apartment near a cemetery?” Indeed, it faced the Horst Wessel Friedhof, named for the composer of Nazi marching music. “My new job is around the corner,” he said, excitedly. I imagined him and his little girls walking past Joste Strasse on their way to and from work and day care. They will be part of the newest cycle of Jewish life in Berlin.

When our family gathers for Passover, we’ll end the Seder with the traditional, “Next year in Jerusalem.” I will be silently thinking, “Ach du Lieber – OMG, next year in Berlin!”

Mindy Stern is a writer who is working on a book about the lives of medical residents and fellows. Follow her at www.mindysternauthor.com

Go Up to Israel not egypt/berlin