Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

10 min read

Although separating children from their parents saved them from death, it left emotional scars that would last a lifetime.

Watching Ukrainian women and children flee Putin’s death machine as men remain to fight evokes a heart-rending image from my family narrative 84 years ago.

In 1939, my wife’s maternal grandparents parted from their beloved daughters, Gertrud, 8, and Erika, 10, at the railroad station in Graz, Austria. The girls boarded a kindertransport (transport for children) to Sweden. Barred from the platforms as Jews, their parents strained for a final glimpse at their departing daughters.

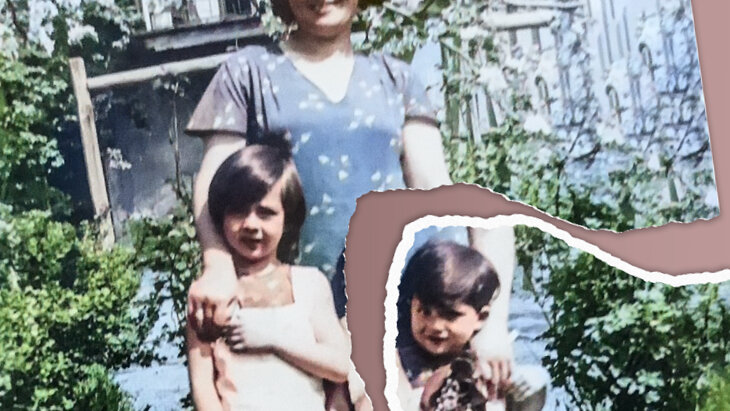

Trude and Maja, 1939

Trude and Maja, 1939

Sundering the Silber family devastated the adults and bewildered the girls but it saved the daughters from the Holocaust. It also imbued Gertrud, called Trude, who would be my mother-in-law, with lifelong pangs of abandonment and want. Too young to comprehend the situation, she could not understand the absolute necessity of her parents’ action. She did not experience it as an act of love.

When she reunited with her parents in Palestine after the war, Trude carried pain and resentment. The reunion was far from joyous; it was uncomfortable and contentious. Nor was this unusual, as is painfully related by testimony in the documentary “Kindertransports to Sweden,” (Menemsha Films, Santa Monica, California, U.S.A).

Trude bore this emotional wound for her entire life, from Sweden to Palestine, as Palestine became Israel, and to her final refuge in the United States. In her final days, in a hospital in Somerset County, New Jersey, she unburdened herself to me over 48 hours, having surprised me with the request that I spend that time alone with her to record her final thoughts to her daughters and other family members. Her life story was at once commonplace and extraordinary.

Born in Austria in 1931, Trude’s childhood in Graz, the country’s second largest city 200 km south of Vienna, was happy. She lived in a comfortable apartment with her parents and older sister, Erika, and they attended public school, engaging in normal childhood activities. Her world and that of every Jew in Austria crashed with the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria into the German Reich, March 13, 1938, and exploded with Kristallnacht eight months later.

Her world and that of every Jew in Austria crashed with the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria into the German Reich, and exploded with Kristallnacht eight months later.

The horrors of the Nazi regime are well known; Trude and her family suffered all of them. Her father lost his small manufacturing company, and the extended family was evicted from their homes – five nuclear families crammed into her grandfather’s small apartment.

One night, without warning, the Gestapo burst in, “Jews, get out!” They carted the adult men away to Dachau, at the time an internment camp, not yet a death camp.

The Silber family in happier times. Margarete Silber with daughters Erika and Gertrud (right), circa 1934

The Silber family in happier times. Margarete Silber with daughters Erika and Gertrud (right), circa 1934

“It was made clear to us that not only were Jews unwanted, but they were also inferior, no better than animals, vermin,” testifies a kindertransport survivor.

Trude was first abused in school, then expelled. All her gentile former friends shunned her. When she contracted scarlet fever, she was isolated in a sanitarium and left untreated, while gentile children received care.

“These two are Jews whom we don’t want. You can do to them as you like.”

“My brother went to school the first day after the Anschluss and came home very happy,” said another kindertransport survivor in the documentary. “Today was a special day. Mr. Jakobowski, the teacher, had greeted them with a Hitler salute and rehearsed the salute with them.” But days later, that same teacher asked two boys to come to the front of the classroom and addressed the class, “These two are Jews whom we don’t want. You can do to them as you like. You can insult them; you can even beat them up.” And so, several boys went to the front of the class and slapped them.

Facing this intensifying menace, Trude’s parents decided the family should flee to the British mandate in Palestine. They were able to secure entry visas for themselves and Erika, but not for Trude. Neither Erika not Trude knew the precise emigration procedure their parents used or what authority barred Trude, only that she was refused entry because, at age 8, she was too young.

In desperation, the parents decided their only recourse was to divide the family, dispatching Trude, with Erika as a companion and guardian, to Sweden on a kindertransport while they themselves fled to Palestine.

Jewish children arrive in the Harwich, Great Britain, Dec 12, 1938, on a Kindertransport

Jewish children arrive in the Harwich, Great Britain, Dec 12, 1938, on a Kindertransport

More than five years before Trude’s flight, German Jewish aid organizations had contacted Jewish congregations in Sweden to explore potential cooperation in the rescue of persecuted and threatened Jews. They established communications channels, quickly taken over by the Central Committee for Aid and Reconstruction in Berlin and the Aid Committee of the Jewish Congregation in Stockholm. The initial goal was not to relocate Jews from Germany and Austria to Sweden, but rather to provide financial support to Jews fleeing to Palestine. Their intention was to pay for travel expenses, guarantee money required by the British Mandate, and accommodations at the Ben Shemen kibbutz, about 45 km. northwest of Jerusalem. The possibilities for relocation from Germany and Austria to Sweden looked dim since the country’s Alien Act required prepayment of living expenses for immigrants.

The horror of Kristallnacht on the night of November 9–10, 1938 shocked the Swedish for the better, paving a path to safety for Continental Jews, especially children. The Swedish government granted temporary residence permits for a maximum of two years, although the children wound up staying until Germany’s defeat in 1945. The limit was 20 children in any one group, and private Swedish groups or individual citizens had to guarantee their financial sustenance.

Trude longed not to leave her family, especially her mother, and had no understanding of the imperative that they all escape the Nazi regime by any means possible. At age 7, Gertrude Fletzberger, another child survivor, realized, “I’m alone. My siblings are gone. I must fend for myself.”

A Kindertransport

A Kindertransport

In the documentary “Kindertransports to Sweden,” Hans Wiener, a 14-year-old German Jew who, at 14, escaped the same year as Trude, reported a nightmare in which he was holding his mother’s hand when their grip slipped and suddenly, he was alone. Another survivor recalled, “The last thing I remember consciously is my parents waving goodbye to us” as the train pulled away from the platform. “My mum was crying.”

Trude was one of just 500 children granted refuge in Sweden via kindertransports. Great Britain admitted 10,000, compared with 1.5 million children murdered in the Holocaust.

Trude and Erika arrived in Stockholm, Sweden, together, but were quickly separated, sent to different families without either one being told where the other was. Trude’s first foster family had no children, spoke no German, and were practicing Christians. Trude later learned they had been hoping for a child old enough to help with sewing, cooking, and housework. For unknown reasons, she was placed in the third grade, although in Austria she had just completed the first grade. Skipping a year and attending class in a language she did not understand, she struggled academically, and believed that struggle stunted her education for life.

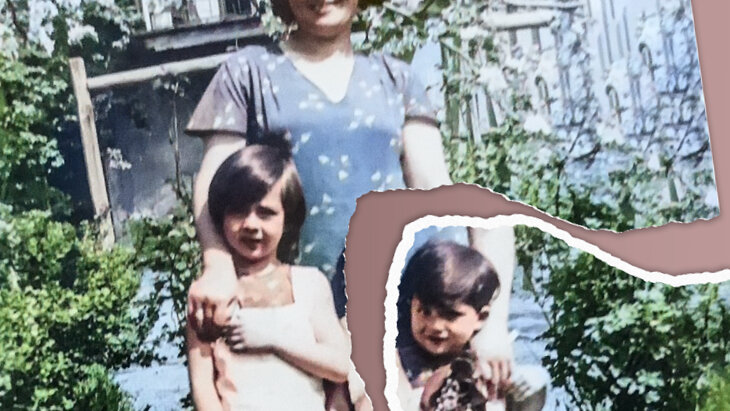

Trude, 1943

Trude, 1943

Although unloving, the foster family was kind to Trude, gave her a private bedroom, fed, and clothed her, and provided the other tangible necessities of life. Her time there was brief. At school, she became friends with a Swedish girl. Brigitte, who asked her parents if Trude could live with them. The parents consented, and Trude moved.

Again, the foster parents provided for her physical needs, but no show of affection. They were kind, but not nurturing. Brigitte readily shared half her clothing allotment, limited by wartime rationing. Trude continued at school, learning Swedish, enduring occasional “Dirty Jew!” curses, but remaining close to Brigitte and enlarging her circle of friends.

When Trude was in the sixth grade, her foster mother contracted cancer, and so Swedish authorities transferred her from the foster parents’ house to a group home where she was happily reunited with her sister, Erika.

Her greatest difficulty was navigating the difficult teen years without the guidance and love of a mother. At age 13, Trude learned her parents had escaped to Palestine. Erika corresponded with their mother, but Trude did not. She did receive a couple of letters from her mother, and when Trude was 16, her parents arranged for her and Erika’s entry to Palestine.

When Trude arrived in Palestine, it was a nascent society, fighting for existence amid hostile powers under a British administration with decidedly mixed attitudes toward it and Jews in general. She had left an affluent, modern, Western democracy with comforts unknown in Palestine, moving from a house with her own bedroom to a two-room apartment occupied by two families. In Sweden, she’d been insulated from the ravages of World War II; in Palestine, she found herself at age 17 fighting in the Israeli Defense Force for 18 months in the war for independence. At 19, she married, and her husband served in the IDF as a tanker.

Max & Trude Tepperberg Wedding Photo, August 15, 1950

Max & Trude Tepperberg Wedding Photo, August 15, 1950

More burdensome than the physical discomfort was the emotional stress of Trude’s feelings of abandonment by her parents. If humans were Vulcans – all intellect, no emotion – she would have appreciated the necessity of the separation, and not resented it. But she carried the hurt and insecurity of her childhood to Palestine, straining her relationship with her mother and father. She felt disconnected from her mother and fought with her father and felt both parents were treating her like the eight-year-old they had put on a train almost a decade earlier.

Erika suffered a psychological breakdown, was given shock treatment, and had a contentious relationship with everyone. Stunningly, her father remarked that they would all have been better off if the airplane from Sweden had crashed and killed both girls.

Her emotional scars were not uncharacteristic of kindertransport survivors. In “Kindertransports to Sweden,” one survivor reports shredding his only photographs of his parents, killed by the Nazis, out of anger over his perceived abandonment. Another survivor said that she did not mourn her parents’ deaths, so bitter was she over similar perceptions.

The joyful highlights of the time in Palestine/Israel were the births of Yael, when Trude was 21, followed by Eli three years later.

Two years after Eli’s birth, Trude and her family emigrated one final time, to the state of New Jersey in the United States. Her third child, Susan, was born in America, and, for more than six decades, she enjoyed a level of security and contentment not experienced since her childhood before the Holocaust.

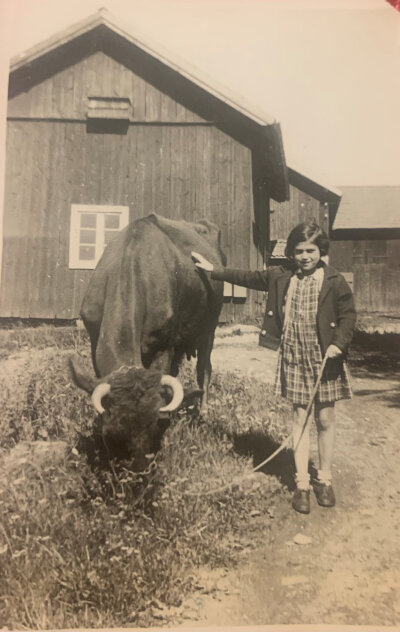

Trude at 88

Trude at 88

In September 2019, as she lay dying in a hospital bed, she unburdened herself to me with feelings of determinations, resignation, and triumph about the satisfactions and misgivings of her life. She related her feelings of love, pride, joy, and regret as a sister, mother, and grandmother – as the substance of the eulogy she hoped I would deliver at her funeral, which of course, I did. Although I had known her for more than four decades, this tale, freighted with horrors I could barely imagine, broadened and deepened my appreciation for this woman.

The doctors then told us she had days, perhaps hours, to live. We honored her request to die at home, moving her to hospice care in her own bedroom. Her three children and their spouses, joined by three of her four grandchildren, surrounded her. My youngest daughter laid Trude’s great-granddaughter, just three months old, in her lap, providing in her final moments a presence of love and support that I hope mitigated her lifelong pangs of abandonment.

Then she passed.

INTERESTING, Thank you for writing about all this. People should not forget. I am now 90, I was 8 when the Nazis killed my parents, and our family. Since then, I have suffered from a Love Deficiency. My 2 children and their little family don't understand. Yes, I have a hole in my heart that..... however I still giggle a lot (French women do, regardless of,,,). Again thank you for writing.