Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

7 min read

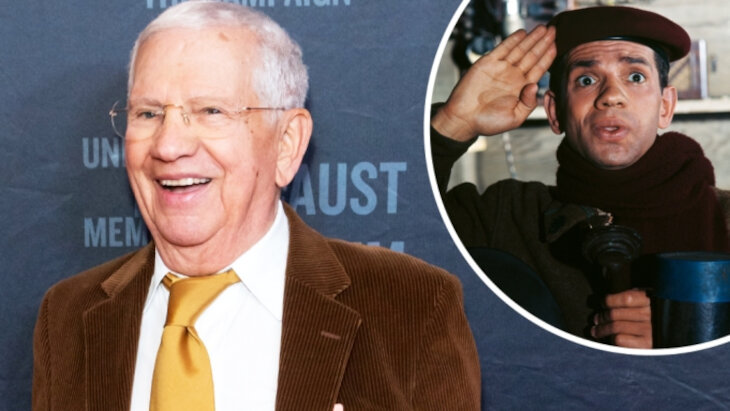

The actor Robert Clary, 96, has died. Here is his harrowing story.

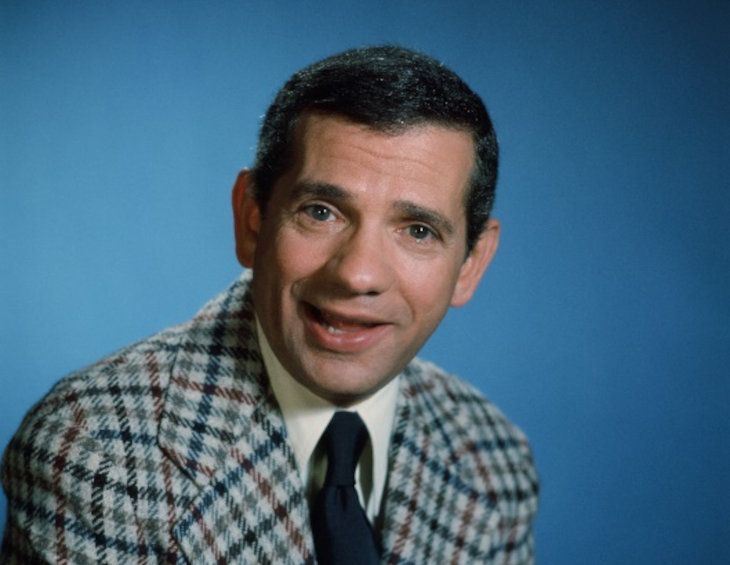

Fans of Hogan’s Heroes - which featured a group of Allied POWs outwitting their hapless German captors during WWII - might not have known they were watching people with real-life experiences of the war.

The show’s cowardly camp commander Col. Klink was played by Werner Klemperer, a German Jew and the son of world-famous orchestra conductor Otto Klemperer. Dim-witted Sgt. Shultz was played by John Banner, a Jewish refugee from Austria.

However, none of the cast’s stories were as harrowing as that of the actor who played French POW Corporal Louis LeBeau, Robert Clary, who died on November 16, 2022 at the age of 96. Robert played Cpl. LeBeau for laughs; his jokes hid his harrowing experiences of the Holocaust.

In the aftermath of the First World War, tens of thousands of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe moved to France, which had some of the most liberal immigration policies towards Jews at the time. Among the many Jews who made Paris their home were Moishe and Baila Widerman, who moved from Poland to a cramped apartment on Paris’ picturesque Ile St. Louis, in the middle of the Seine river.

Moishe’s first wife died in childbirth; he married Baila and they had a further eight children together. Robert Widerman (he changed his name to Clary later on) was the youngest, born in 1926. He was always a talented entertainer, and while he was still a child he got a job singing on a weekly radio show. Though poor, Robert later recalled his childhood as extremely happy.

With the election of Hitler in 1933, Jews began pouring into France in even larger numbers. By 1940, there were approximately 350,000 Jews in France, most of them recent immigrants.

They came under German control in May, 1940, when Germany invaded France. France signed an armistice with Germany the following month, and installed a military commander to control northern and western France. (Southern France was governed by an ostensibly independent French regime which collaborated with Nazi Germany.) Jews were stripped of their rights and forbidden from entering public spaces such as parks, theaters and restaurants. Jews were arrested and terrorized; many were shot by the occupying forces.

On January 20, 1942, the Nazi regime decided their persecution and murder of Jews wasn’t vicious enough. On that date, in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee, Nazi leaders adopted the “Final Solution,” the codename for systematically killing every Jewish man, woman and child in Europe. The participants planned to commit murder and genocide on a scale the world had never seen. In France, implementation of this heinous policy meant that tens of thousands of Jewish families were sent first to the Drancy concentration camp on the outskirts of Paris, and from there to concentration camps, mainly Auschwitz, where most were murdered on arrival.

The Widerman family were among the 77,000 French Jews who would ultimately be deported and murdered. French police officers, working with Gestapo officials, came for them on September 23, 1942. Every Jew in the Widermans’ building was ordered outside. Men and women were separated. “Nobody knew where we were going,” Robert later recalled. “We were not human beings anymore.”

Before she was forced onto a transport to Auschwitz, Robert’s mother had a desperate plea for her fun loving and boisterous son. “Do what they tell you to do. Tantrums won't work anymore. I won’t be there to protect you.” Robert never saw his mother again. He was 16 years old.

Robert was sent to Blechhammer, a sub-camp that made up the vast Auschwitz complex. 4,500 Jews passed through Blechhammer, performing slave labor for various local companies and industries. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum describes the working conditions at Blechhammer:

The labor the prisoners performed was typical construction work: excavating for foundations, building roads and structures, and transporting building materials. In the latter instance, they used prisoners to pull the wagons instead of horses or tractors. Eight prisoners would be harnessed to a wagon. They used physical coercion to force the hungry and weak prisoners to work. The prisoner-foremen supervising the prisoners during work never parted from their bats, which they put to use often. The prisoners worked all day, from dawn to dusk, for about 10 to 12 hours. They also worked at the construction site every other Sunday. On alternate Sundays, they were put to work at various jobs within the camp.

At Blechhammer, Robert’s performing skills enabled him to survive. He sang in weekly Sunday performances, gaining the favor of the SS guards who patrolled the camp. “Because I entertained, sometimes I would receive an extra piece of bread and another bowl of soup,” he later wrote.

In the beginning of 1945, as Soviet forces began to close in on Auschwitz, the prisoners of Blechhammer were sent on a death march to a different concentration camp, Gross-Rosen. 4,000 prisoners were driven on a brutal two-week march through the bitter cold winter snow; most died on the way.

“If you sat down to rest or were too weak to go on,” Robert later recalled. “You were shot by one of the guards. Twice during those two weeks, they gave us a piece of bread.” As the Allies continued to draw closer, prisoners from Gross-Rosen and other camps were sent to Buchenwald, which swelled to 112,000 prisoners at the close of the war.

Robert was liberated by American troops on April 11, 1945. He returned to Paris to find that both of his parents were murdered in the Holocaust, as were ten of his siblings. One of his sisters, Nicole Holland, fought with the French resistance, smuggling guns and messages to fighters and giving aid and directions to arriving Allied forces. He lived with her and a second sister who’d also managed to evade death.

In Paris, Robert Clay sustained himself by performing. He adopted the stage name Clay from the title of a movie he liked and performed in nightclubs and made records. His records became popular in the United States, and in 1950 Robert abandoned France to build a new life for himself in the US.

Hogan’s Heroes

Hogan’s Heroes

He found some success, appearing in several Broadway musicals, including Irma La Douce and Cabaret. “I loved to go to the theater at quarter of 8, put the stage makeup on, and entertain,” he later described. He got to know a number of American stars, including the comedian Edie Cantor. In 1965, Robert married Cantor’s daughter, Natalie Cantor Metzinger, who predeceased him in 1997.

That same year, Robert began acting in the TV show Hogan’s Heroes. At only a little over five feet tall - perhaps because his teenage years were blighted by starvation - his short stature was played for laughs, as was his French character. When Hogan’s Heroes was attacked for being tasteless in the way it made light of a Nazi-run POW camp, Robert would brush off the criticism. “It was completely different,” from the experiences of Jews in the Holocaust, Robert explained. “I know (POWs) had a terrible life, but compared to concentration camps and gas chambers it was like a holiday.”

For years, Robert never spoke about his experiences during the Holocaust. That changed in the 1980s when he observed people minimizing or even completing denying that the Holocaust had ever taken place. “They write books and articles in magazines denying the Holocaust, making a mockery of the six million Jews - including a million and a half children - who died in the gas chambers and ovens,” he said in a 1985 interview. Robert began speaking about his experiences in schools. He wrote two memoirs and took part in documentaries about the Holocaust. “His point was always: Never hate,” his niece Brenda Hancock told the New York Times after his death. “Despite his experiences in the concentration camps, he always looked for beauty, and to make life joyful for everyone else.”

“I beg the next generation not to do what people have done for centuries - hate others because of their skin, shape of their eyes, or religious preference,” Robert Clay explained.

Watch an interview with Robert Clay about his experiences during the Holocaust:

My wife's father came to visit us - and while there - Robert Clary - was giving a talk at a local theatre. We were able to take him to the show. At the end - he got to actually meet and spend a couple of minutes talking with Robert. That really impressed my father-in-law.