Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

11 min read

The famous ruler created the Pale of Settlement and shaped Jewish life for generations.

Catherine the Great is in the news lately. Long known as Russia’s great modernizer, Catherine championed public health during her reign from 1762 to 1796, and a letter she wrote urging nationwide vaccinations against smallpox recently sold at an auction for a record sum. The hit show The Great, starring Elle Fanning, depicts Catherine’s rise to power.

Empress Catherine was the first person in Russia to be inoculated against smallpox; her husband, Peter III had been disfigured by the disease. Many historians regard Catherine as an enlightened ruler and her reign as a Golden Age in Russia. Yet when it came to Jews, Catherine was markedly less liberally inclined. Here are five facts about Catherine the Great and the many Jews over whom she ruled.

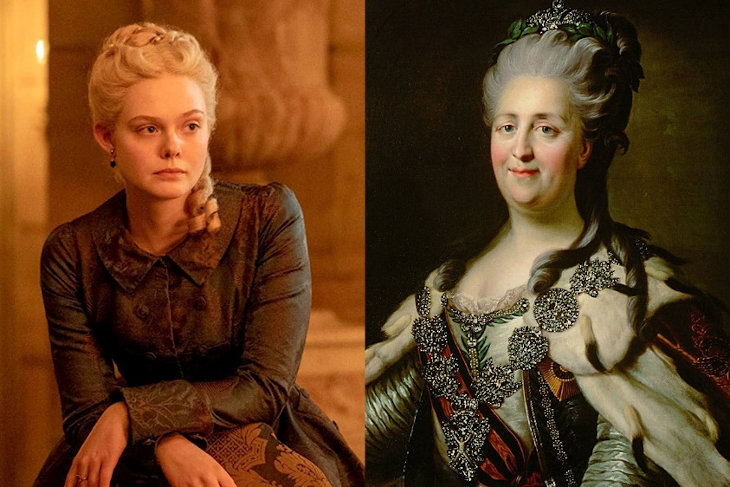

Elle Fanning as Catherine, and a portrait of the Russian ruler.

Elle Fanning as Catherine, and a portrait of the Russian ruler.

Catherine became one of Russia’s best-known rulers, but Russia’s ways were initially foreign to her. Born into a noble Prussian family in 1729, Catherine was originally named Sophie and grew up speaking German. When she was fifteen years old, Russia’s brutal Czarina Elizabeth Petrovna invited her to Russia in order to marry Peter, Elizabeth’s nephew and heir to the throne. Before she married Peter, Sophie converted from Lutheranism to Russia’s official religion, Orthodox Christianity, and changed her name to the Russian-sounding Ekaterina (“Catherine” in Western spelling).

Jews who refused to abandon their faith were generally barred from living in the interior of the country.

The Russian royal family Catherine married into was intensely antisemitic. Peter the Great ruled Russia from 1682 to 1725 and famously declared that he would “prefer to see in our midst nations professing Mohammedanism and paganism rather than Jews. They (Jews) are rogues and cheats. It is my endeavor to eradicate evil, not to multiply it.”

Jews were largely banned from living anywhere inside of Russia. Converts to Christianity were tolerated, but Jews who refused to abandon their faith were generally barred from living in the interior of the country.

Peter’s daughter, the Czarina Elizabeth – the one who brought Catherine the Great to Russia in order to marry her heir – was no friend to Jews either. Styling herself a defender of the Christianity, she seized power in a 1741 coup during which she wielded a large silver cross and declared that she was opposed to all “enemies of the Christian faith”. The following year, 1742, Elizabeth signed an Order of Expulsion, making it illegal for any Jew to remain in Russia.

That radical law was maintained even as Russia expanded westward, acquiring territories that were home to Jewish communities. When the city of Riga (formally ceded by Sweden to Russia in 1721 and today the capital of Latvia) petitioned Elizabeth to allow Jewish merchants to remain, Elizabeth declared, “I do not wish to obtain any benefit or profit from the enemies of Jesus Christ” and insisted the Jews of Riga depart or convert to Christianity if they wished to stay. Historian Martin Gilbert estimates that about 100,000 Jews lived in Russia by 1770, but their presence was barely tolerated and little acknowledged by Russian officials.

In contrast to the Russian royal family, Catherine the Great seems to have harbored a less visceral hatred of Jews. After wresting power from her husband in 1762 in a coup, Catherine installed herself as Empress of Russia. One of her first acts, in 1763, was to issue an “ukaz,” or decree, allowing foreigners to settle in Russia for the first time. It’s widely assumed that the foreigners she hoped would settle in Russia were ethnic Germans like herself, whose presence, she assumed, would help modernize her adopted country. However, one notable loophole in the rule made it illegal for foreigners who were Jews to settle in Russia.

Jews were excluded from this decree – yet in some specific cases, Catherine directly intervened. She allowed some Jews to live in the city of Riga, for instance. Catherine had set up a special bureau to regulate “foreigners” in Russia, and on May 11, 1764, Catherine wrote to the Governor General of the city of Riga, asking that he allow Jewish merchants to settle in the city and be treated in the same way as any other foreigners. At the bottom of this official letter, Catherine hand-wrote her own postscript in German explaining that she’d written a second, secret, letter ensuring protection for eight specific Jews to travel in Russia and settle in Riga. The merchants included a rabbi named Rabbi Israel Hayyim, a mohel named Lasar Israel, and others. “Halten Sie dieses alles geheim,” Catherine wrote: “keep all this a secret.”

It seems that Catherine the Great intervened in other instances to guarantee the rights of some Jews to live in Riga and St. Petersburg. In 1769, she relented further, and allowed Jews to settle in newly-acquired Russian provinces – particularly the sparsely settled South Russia Steppes – like any other “foreigners” in her kingdom.

In a series of intensely turbulent alliances, Catherine the Great allied herself with Prussia and Austria and succeeded in partitioning the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In 1772, Poland was carved up and Catherine found herself ruler of an additional 600,000 Jews from her new territories. With the second partition of Poland in 1793, Catherine gained 400,000 more Jewish subjects. In 1795, she gained more territory, adding 250,000 new Jewish subjects. Catherine the Great thus found herself ruler of the largest Jewish community in the entire world.

She didn’t seem to like Jews very much. Taking a tour of some newly acquired territories, Catherine noted that the local Jewish population (but not others, in her opinion) looked “horribly filthy.” Yet she didn’t seem to hate Jews with the same visceral intensity of previous czars and czarinas, and she eschewed her predecessors’ extreme violence towards their Jewish subjects. (For instance, when Czar Ivan “The Terrible”, who ruled Russia 1530-1584, conquered the town of Pskov, near Estonia, he ordered all the Jews living there to be drowned in the Velkaya River that ran through town.)

According to the Russian-born historian Herman Rosenthal, who served as Chief of the Slavonic Department of the New York Public Library, scholars were divided in their opinions about why Catherine seemed loath to persecute Jews the way previous czars and czarinas did. As an outsider, she seemed to have grown up without some of the deep-seated anti-Jewish feelings that some Russians harbored.

Catherine issued a series of edicts governing her new territories in Lithuania and Russia, guaranteeing all residents equal rights. Most of her edicts contained the phrase “without distinction of religion or nationality.” In 1772, soon after the first large group of Polish Jews became Russian subjects, Catherine issued an edict guaranteeing that “Jewish communities residing in the cities and territories now incorporated in the Russian Empire shall be left in the enjoyment of all those liberties with regard to their religion and property which they at present possess.” It was a promising decree, guaranteeing the continuation of Jewish life in Eastern Europe – for a time.

Yet Catherine wasn’t always so benign. Facing intense pressure to continue Russia’s longstanding policy of not allowing Jews to live inside Russia proper, Catherine restricted the rights of her new Jewish subjects, insisting they remain in Poland and Lithuania. In December 1791, she created a formal “Pale of Settlement” in the western part of Russia’s territory, where Jews could live. Other parts of Russia were strictly off-limits. (The term Pale came from the Latin Palus, meaning a stake: it refers to a boundary or marker delineating property or land.)

The boundaries of the Pale of Settlement shifted through the years. Later on, Catherine added lands conquered from the Ottoman Empire. She also encouraged Jews to move to the area around Odessa in Ukraine. With Catherine’s encouragement it soon became one of the major centers of European Jewry and saw a flourishing Jewish life for generations. (The boundaries of the Pale were finally formalized in 1812, when Czar Alexander I decreed that 25 provinces stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea were the only regions in Russia in which Jews could live or travel without special permission.) Jews could petition to live outside the Pale of Settlement – this is where the term “beyond the Pale” comes from – but their applications were nearly always denied.

The Pale of Settlement wasn’t Catherine’s only attempt at social engineering when it came to Jews. Ever the reformer, Catherine created major new social categories in Russia, including serfs, urban dwellers, merchants, small town dwellers, etc. Jews were allowed to enter the urban categories (called soslovie in Russian) and be classified either as city dwellers or town dwellers. Jews thus classified were technically not supposed to live in the countryside and in villages, but this ban was applied very unevenly. Some Jews were forced to move into towns while others were allowed to remain in their small villages and shtetls.

In 1785, Catherine the Great decreed that Russia’s Jews were “foreigners” and entitled to all the rights and protections that she offered non-Russians living in her territories. No matter what, unless a Jew converted to Christianity, they could never be considered a Russian, not even a naturalized citizen. She further restricted Jews’ business opportunities in 1792 when she ruled that Jews couldn’t enter into the guilds of merchants in Moscow and in the city of Smolensk. The distinction between Jews and Russians, always visible, was slowly becoming wider.

Finally, in 1794, Catherine formally declared that Jews were “foreigners” who were completely separate from Russians, and doubled the taxes that Jews had to pay. It was an ominous move and set the tone for the way Jews were treated as a separate entity – at times as an enemy within – in Russia for the next two centuries.

Historian Max Diamant notes that Catherine, as well as her successors, did all they could to safeguard the minds of Russian peasants, called muzhiks, from the supposedly malign influence of Jews. In this way, “the mind of the muzhiks, the Russian peasant, had to be kept docile and ignorant. Though the Jews could roam throughout Poland, Lithuania, and the Ukraine, in Holy Mother Russia itself, where dwelt the muzhiks – 95 percent of the population – they could not.”

While she afforded Jews some rights, she also restricted their movements and made them beleaguered foreigners in their own country.

Considered a malignant grouping, Diamant notes that Jews were kept so thoroughly separate that when Russian peasants first arrived in Moscow during the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and saw modern inventions, they believed that modern conveniences had been created by magical, demonic Jews. Though the Russian empire was home to millions of Jews by then, most people living within Russia proper had still never met a Jew in their lives – thanks to the legacy of separate communities and the Pale of Settlement that Catherine the Great invented and championed.

Catherine the Great is remembered today in much of the world as a reformer, an enlightenment thinker, and idealist, who attempted to modernize Russia. Her long reign was a time of turbulence, war, and great victories for the vast Russian empire she ruled. Yet for Russia’s Jews, Catherine the Great was a complex figure. While she afforded Jews some rights, she also restricted their movements and made them beleaguered foreigners in their own country.

Her legacy continues to this day. Jews continue to live in large numbers in the areas of the Pale of Settlement that Catherine the Great established. And the stigma of Jews as “foreign” and somehow malign in Russia lives on today. A recent poll found that half of Russians feel that Jews have “too much power”. It’s a sentiment that wouldn’t have been out of place during Catherine the Great’s long, tumultuous rule – and one that her policies helped create.

Suggested further reading: