Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

9 min read

One of the greatest black leaders of modern times dreamed of a very different and brighter future for the two communities.

The African-American community is diverse and many Blacks – particularly committed Christians – are strong supporters of Israel and the Jewish people. However, the surge in Black antisemitism is indisputable. An ADL study from 2016 shows that antisemitic attitudes among the Black community are twice as prevalent as the rest of the population, and anecdotal evidence implies the problem is only getting worse.

It’s not only Kanye West’s infamous diatribes against the Jews and his adoration of Adolf Hitler that is disturbing. Black athletes DeSean Jackson, Stephen Jackson and even LeBron James unabashedly tweet antisemitic tropes, and young Black men assault Orthodox Jews in New York City.

Strangest of all, the Black Hebrew Israelite movement claims that they are the “real” Biblical Jews, while Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews are “imposters.” Long considered a marginal fringe group, the Black Hebrews now count a million and a half followers - and they are growing.

When Kyrie Irving was suspended by the Brooklyn Nets for promoting an antisemitic movie, Hebrews to Negroes, hundreds of Black Hebrew Israelites demonstrated outside of the Barclay Center in Brooklyn, yelling “We are the real Jews!”, echoing Kani Zabach, founder of the Black Israelite sect House of Israel, said three years ago: “Blacks are the real Jews, you’re damn right we are. And we are coming to take back our identity and our nationality.”

Though the Black Hebrew Israelite movement was only founded in the late 19th century, its “replacement” ideology is far older. When Christianity first broke away from its Jewish roots in the second century, many of its leading thinkers claimed that the Christian Church had “replaced” the Jews as God’s covenanted chosen people. Widely accepted throughout the Christian world for most of the last two millennia, replacement theology has, in the words of Thomas Ice, “provided the basis for all sorts of mischief, persecution, and atrocities against the Jewish people throughout Christian history.” Though many modern Christians reject this theology and wholeheartedly embrace the Jewish people, replacement theology is gaining traction in the black community.

No peoples have suffered more from racism and persecution than Jews and blacks. Our peoples are natural allies, not enemies.

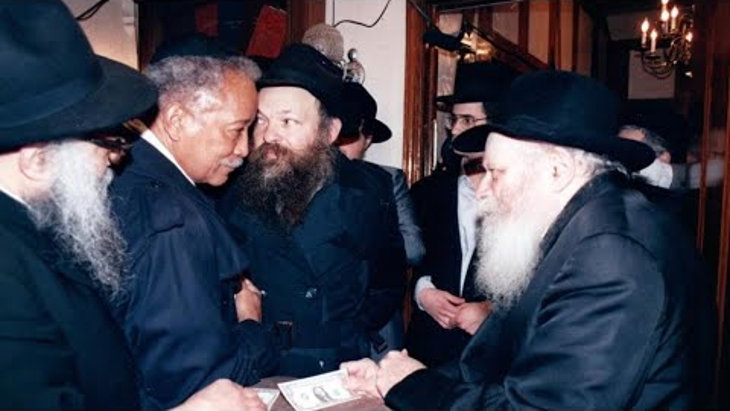

It didn’t have to be this way. Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the famed Lubavitcher Rebbe, believed the Jewish and Black communities are bound together by shared beliefs and painful histories. When former New York City Mayor David Dinkins visited the Rebbe after the Crown Heights riots of August 1991, the mayor asked for the Rebbe’s blessings to “bring peace to both communities.” But the Rebbe saw things differently, telling the mayor that “we are not two communities – but one community, under one administration, under One God.” No peoples have suffered more from racism and persecution than Jews and blacks. Our peoples are natural allies, not enemies.

Mayor David Dinkins meeting The Lubavitcher Rebbe

Mayor David Dinkins meeting The Lubavitcher Rebbe

The Lubavitcher Rebbe was not the first to recognize the natural affinity between Jews and blacks. Over 120 years ago, another man - one of the greatest Black leaders of modern times – dreamed of a very different and brighter future for our two communities.

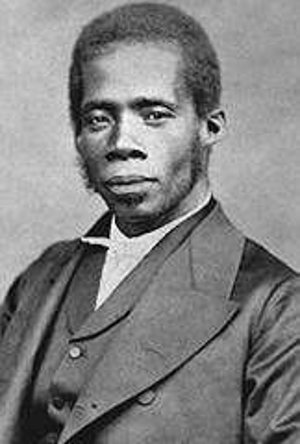

Born as a free Black in 1832 in Charlotte Amalie, the capital of St. Thomas and the Danish West Indies, Edward Wilmot Blyden witnessed slavery firsthand. St. Thomas was home to the biggest slave market in the Caribbean, and most of the residents of the island were Black slaves. Though expected to become a tailor like his father, Blyden was set on becoming a clergyman to help relieve the suffering of the black community.

Edward Wilmot Blyden

Edward Wilmot Blyden

At 18, Blyden moved to New Jersey and applied to the Rutgers Theological College, where he was rejected because of the color of his skin. The traumatic experience embittered Blyden, convincing him that the Black community could only achieve equality by “returning” to their African homeland.

After his rejection from Rutgers, Blyden emigrated to Liberia, a new nation established by freed slaves from the Americas, where he became one of the new nation’s most accomplished citizens. He served as a clergyman, educator and diplomat, and most importantly as the leading philosopher of black nationalism. Several of his books, like Vindication of the Negro Race and African Life and Customs became classics, the foundation upon which all black nationalist thinkers in the 20th century would build.

Blyden’s nationalist philosophy was a response to the discrimination and degradation that blacks experienced in America.

Blyden’s nationalist philosophy was a response to the discrimination and degradation that blacks experienced in America. He angrily writes about how he was refused entry to Congress in Washington, DC in 1862, even though he was a well-known diplomatic representative of Liberia, and was then suspected of being a runaway slave and forbidden from leaving the city by the Fugitive Slave Law.

Dehumanizing experiences like these – daily fare for American Blacks – was deeply damaging to the dignity of the black community. For Blyden, strengthening the community’s pride was critical to their progress and liberation. He insisted that the word “Negro” always be written with capital letters.

Significantly, Blyden did not believe that “black pride” should come at the expense of other races or religions. He dreamed of a revitalized Africa serving as a link between the Middle East and Western civilization, a way to “destroy race enmities” and “reconcile nation with nation.” Most surprising, however, was Blyden’s fascination with another long-suffering race: the Jewish people.

Growing up in St. Thomas, Blyden lived in the Jewish neighborhood of Charlotte Amalie. His friends were primarily Jewish, and their favorite playground was “Synagogue Hill.” He often visited the synagogue with his friends, and later wrote of his admiration for the dignified and meaningful atmosphere of Jewish services. He was enthralled by the stories of the Hebrew Bible and enchanted by the Hebrew language.

As an adult, he was driven to master Hebrew, the language of the Bible, in order to refute Christian racists who frequently cited biblical verses to justify their persecution of blacks. Blyden was also fascinated by the history of the Jewish people, repeatedly referring to them in his writings. He even visited the Holy Land, “the original home of the Jews – to see Jerusalem and Mount Zion, the joy of the whole earth,” writing a book about his travels, From West Africa to Palestine.

Like so many others throughout the generations, he was deeply moved by his visit, writing years later that “the impression made upon me by the visit to the Land of the Patriarchs and Prophets deepens as the years go by, so that with ever fresh interest and delight I recur to the study of the language, literature and history of the Jews.”

Blyden viewed Judaism and the Hebrew Bible as anti-racist.

Most incredibly, in 1898 – only one year after the First Zionist Congress – Blyden published a short, remarkable book entitled The Jewish Question, the fruition of his life-long fascination with the Jewish people. Describing the Jews as “a sacred nation” and “God’s chosen people,” he praised the faithfulness of the Jewish people to their religion. In sharp contrast to Christian replacement theology, Blyden emphasized the Jewish roots of Christianity and Islam, neither of which could have transformed the world without the spiritual foundation laid by the people of Israel, “the world’s leaders in religion and morality.”

Just as important, Blyden viewed Judaism and the Hebrew Bible as anti-racist. Though many Christians distorted the text to support their racist prejudices, a simple Jewish reading of the text clearly rejected the notion of “superior” and “inferior” races. Moses’ marriage to Tzipporah, an Ethiopian woman, and Solomon’s marriage to Pharaoh’s daughter proved that Judaism – and the God of the Jews - was color blind.

Blyden believed that Jews and Blacks were bound together by their analogous histories.

Blyden frequently cited a verse from Amos, in which God says: “To Me, O Israelites, you are just like the Ethiopians, declares God. True, I brought Israel up from the land of Egypt, but also the Philistines from Caphtor and the Arameans from Kir” (9:7). The Hebrew Bible made clear that “the Ethiopian is as dear to Him as the Israelite.”

But Blyden did not stop there. He believed that Jews and Blacks were bound together by their analogous histories. Both peoples “are children of endurance and suffering” brought together by a “history of almost identical… sorrow and oppression.” Both Jews and Blacks withstood generations of slavery – the Jews in Egypt and the blacks in the United States. Each race endured generations of persecution, often at the hands of the same perpetrators. And both peoples continued to suffer in Blyden’s time; the blacks from lynchings and segregation in the American south, and the Jews from murderous pogroms like those in Kishinev and Częstochowa.

Blyden viewed the Jewish people’s endurance through centuries of exile and suffering as a model of hope and renewal for his own people. Jews not only survived, but steadfastly adhered to Jewish observance. They never stopped believing in their singular mission to return to the Land of Israel and bring the light of God to all of humanity. As the “Hebrew captives by the waters of Babylon” never gave up hope of returning to their land, singing songs of yearning for the Holy Land, black men and women sang songs of longing for freedom “that float down the Ohio River.”

The Jewish Question is overflowing with emotion, stemming from decades of friendship with Jews and fellowship with the Jewish people. But the immediate impetus for writing the book was the birth of “the great Zionist Movement,” led by Theodor Herzl, who Blyden referred to as a modern-day Moses committed to liberating his long-suffering people. For Blyden, Zionism was not merely a nationalist movement that would physically restore the Jews to their homeland, but also a spiritual revolution that would awaken the Jewish people, infuse them with pride and enable them to “propagate… the international religion” through which people of “all races, climes and countries [will] call upon the one Lord.” Such a glorious movement could only serve as an inspirational model of liberation and renewal for the black community.

As the Black Hebrew Israelites become increasingly vocal in their mission to “replace” the Jewish people and appropriate Jewish history, we need to do more than denounce their antisemitism. The world would do well to be reminded of the teachings of Edward Wilmot Blyden – that Blacks and Jews, bound together by God, Bible and history, are destined to join together in mutual respect and affection. May we soon see that day.

There was no Israel when Blyden lived. So one can not question his views on his time. But examine his life in Liberia and you will see clearly his opinion on the early example of a Zionist like state for Blacks. How he in the end criticizes the fledgling nation and its treatment of the existing population there.