Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

7 min read

A century after it was originally published, the authentic story of Bambi as a parable of antisemitism is coming to light.

Get ready for a jolting bit of news: Walt Disney’s 1942 film classic “Bambi” was not dreamed up by anyone at the Disney studio. Instead, the film was a saccharine whitewash of a 1922 novel depicting the harsh realities of life in the forest for its animal inhabitants. Written by Felix Salten, an Austrian Jewish journalist and author, Bambi: A Story of Life in the Forest was also a parable about antisemitism.

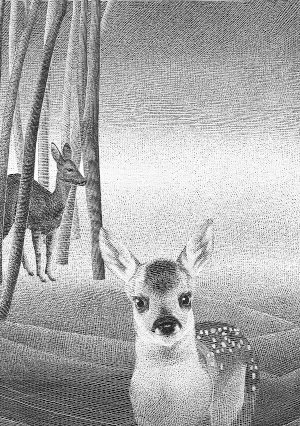

Princeton University Press has just released a new edition of the novel, now faithfully translated from the original German by Jack Zipes and complemented by lovely, stippled illustrations by Alenka Sottler. A full century after its original publishing date, the authentic story of Bambi and its larger political and moral messages is coming to light.

Anyone familiar with the original Disney film will probably immediately think of the tragic scene when Bambi’s mother is shot and killed by a hunter. Other than that shocking incident, the studio made the story into a happily-ever-after tale where Bambi grows up, “marries” Filene and has a family with her, and becomes a confident leader of a forest where all the animals live together in harmony and only human hunters pose dangers.

In contrast, Salten’s original novel is “an allegory about the weak and powerless in the world,” as translator Zipes writes in his introduction. The story’s grimness is readily apparent.

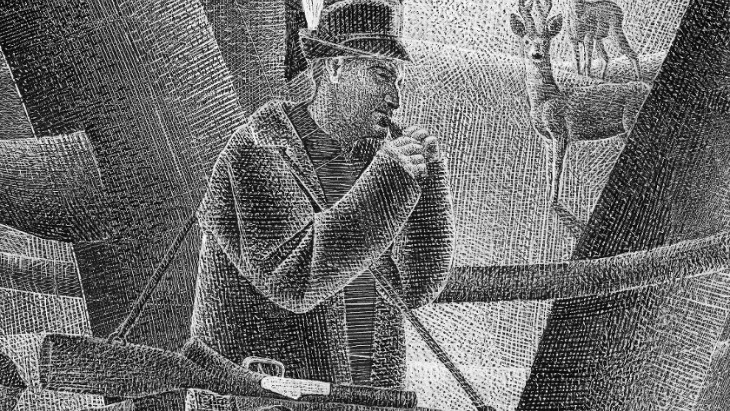

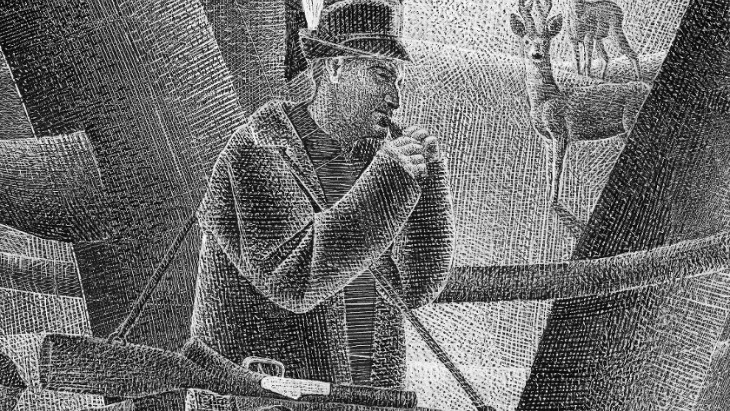

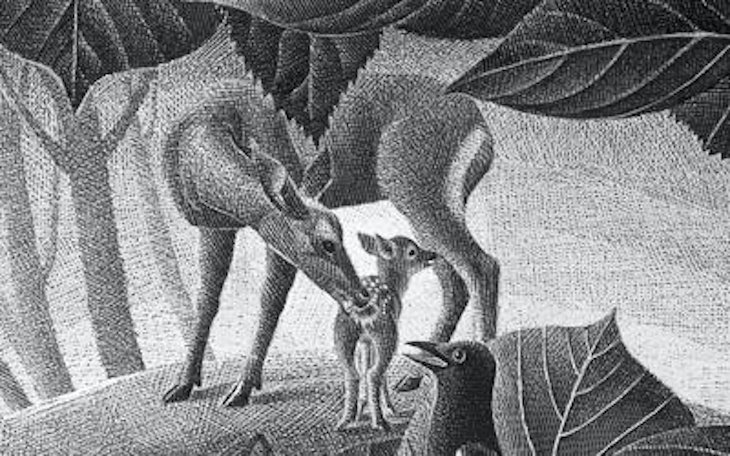

Illustrations by Alenka Sottler from “The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest,” by Felix Salten, published by Princeton University Press in a new translation by Jack Zipes.

Illustrations by Alenka Sottler from “The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest,” by Felix Salten, published by Princeton University Press in a new translation by Jack Zipes.

Many of the animal characters have colorful personalities, but also live with the understanding that life can end in an instant. Bitterly cold winters make food scarce. Summers can be so hot that “the forest was stunned as though hurt by a blinding light. The earth and the trees, the bushes, and all the beasts, inhaled the intense heat with a kind of sluggish satisfaction.” While many of the animals share treasured friendships, animals are also predators. A dog kills a wounded fox. A polecat devours a mouse. Jays fight one another over food. Bambi charges at male competitors over Filene, prepared to kill.

Bambi’s harsh experiences in life, facing constant threats and frequent losses, turn him into a loner—similar to the fate of the writer who conjured him.

The human hunters, known only as “He” or “Him,” are the most petrifying enemies, whose scent instills terror into all the animals, sending them fleeing to safety in nests, burrows, and hideouts in thickets of the forest. Bambi learns to walk in total silence, sidestepping every twig and leaf that might rustle. But inevitably, “He” will catch some animals unaware, leaving the forest bereft of several inhabitants.

Salten’s original novel is “an allegory about the weak and powerless in the world.”

Bambi’s mother teaches him from his earliest days to always be aware of danger, to watch her movements before following. As he becomes a bit older, she warns him that he must learn to live alone one day, remaining ever vigilant of the often invisible and silent dangers surrounding him. When young Bambi cannot understand why his mother will only allow frolicking in the meadow during the nighttime, she explains that daytime is a time of grave danger. Though we all love daylight, his mother says, “we must live this way and be on the alert whenever we move about.”

It is easy to see this as a parable about endangered minority members — particularly Jews — also having to keep watch of their surroundings.

Felix Salten learned this lesson personally. He was born in Pesht, Hungary in 1869 as Siegmund Salzmann, descended from a long line of rabbis on his father’s side. Thousands of Jews lived in the Austro-Hungarian Empire during that time, a number that had swelled as Jews living in the Pale of Western Russia were finally allowed to leave their ghettos to work in the cities where they were usually treated as second-class citizens. Despite their efforts to assimilate and adapt as much as they knew how, Zipes observes, “Adaptation never meant full acceptance.”

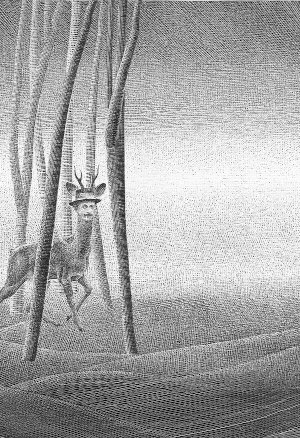

Felix Salten as Bambi, a Jew in the global forest where survival was a challenge. Credit: Alenka Sottler

Felix Salten as Bambi, a Jew in the global forest where survival was a challenge. Credit: Alenka Sottler

The Salzmann family moved to Vienna and identified as Viennese. But antisemitic bullies in school prompted the teenaged Siegmund to “unmark” himself as a Jew, and changed his name to Felix Salten. Drawn to the arts, he became ambitious as a writer and a social climber, and eventually became editor of a magazine called Die Zeit (The Time).

The antisemitism he endured growing up and its growing menace during that era drew him to the writings of Theodore Herzl, particularly his pamphlet Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State). He viewed Herzl as a symbol of resistance and began contributing articles about Jews and anti-Semitism for Die Zeit as well as Herzl’s own weekly, Die Welt. He eventually traveled to Palestine to investigate how Jews were managing to realize the Zionist dream.

His professional success brought him wealth, and he summered with his family near Austrian forests, intensifying his lifelong affection for animals. He later owned a hunting preserve, but as his daughter, Anna, wrote, “Only very rarely did he fire a shot—and then only when the principles of game keeping demanded it.” His stories and novels about animals emphasized their powerlessness, a theme he continued for the rest of his life.

Salten’s own assimilation was no help once the Nazis occupied Austria in 1938.

But his own assimilation was no help once the Nazis occupied Austria in 1938. The following year, Salten and his wife fled to Zurich, after the Swiss extracted a promise from him to stop writing about cultural politics. This limited him to writing far less marketable animal stories.

Salten had already realized that the assimilation he embraced would not protect him from rising antisemitism. He reveals this through the character of Gobo, a childhood pal of Bambi but much weaker physically and emotionally. Long assumed to have been killed, Gobo shocks the forest population by returning, very much alive, and bragging about having been rescued by “Him,” whom Gobo insists is not the evil threat everyone else imagines. Gobo wears a braided ring around his neck, placed by Him, which the deer believes is a special mark that will immunize him from any further danger.

After Bambi and the others scoff at his claims, he tells another friend, “He (Bambi) still can’t deal with the fact that I’ve become someone different. . . There’s no danger for me on the meadow! . . . What does he mean by danger? He means well enough and cares for me, but danger is something for him and the likes of him, not for me.” His confidence that his assimilation will protect him will soon prove as tragically naïve as that of Jews throughout the generations who made similar bargains.

After Bambi and the others scoff at his claims, he tells another friend, “He (Bambi) still can’t deal with the fact that I’ve become someone different. . . There’s no danger for me on the meadow! . . . What does he mean by danger? He means well enough and cares for me, but danger is something for him and the likes of him, not for me.” His confidence that his assimilation will protect him will soon prove as tragically naïve as that of Jews throughout the generations who made similar bargains.

Zipes writes that based on the author’s life experiences with antisemitism, “Bambi is indeed Salten, and Salten is Bambi. . . Just as Bambi becomes an intrepid roebuck, Salten rose to fame and then was belittled and alienated from Austrian and German culture. He was treated just like all the other European Jews in the 1930s and 1940s.”

Despite Bambi’s initial commercial success, Salten allowed Bambi to be translated into English in 1928 by Whittaker Chambers, whose knowledge of Austrian German was limited. It was an error-filled translation that not only missed the true meaning of words but also missed several key messages. (Chambers was later found to have been a communist spy.) Incredibly, Salten sold the film rights in 1933 to American director Sidney Franklin for only $1,000.

Salten died “very much a forgotten loner,” Zipes writes, but left the legacy of this often profound, touching, and sad story, one that had never been intended for children in the first place.