Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

9 min read

Remembering Rabbi Dr. Bernard Lander, the founder of Touro College.

One day in 2005 I got a call from Abe Biederman, a trustee of Touro College. He said Dr. Bernie Lander of Touro wanted to meet regarding a real estate matter. I went down to meet him at his office at 23rd Street.

I had heard about him for years. Dr. Lander had built a school with 29,000 students, possibly the largest school founded by one individual in the last half century in the United States; quite an amazing feat. It had four medical schools, a law school, nursing school, pharmaceutical school, etc. I’d seen pictures of the school’s impressive buildings, with sleek exteriors.

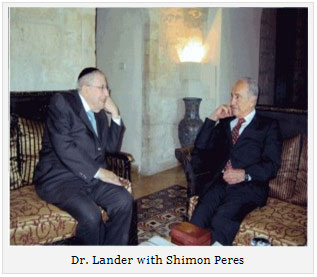

During the course of the prior 30 years Dr. Lander had become somewhat of a legend. Pictures of him appeared with assorted presidents -- Clinton, Bush, Reagan -- senators, foreign heads of state and assorted glitterati. He was frequently in the papers as were articles about some new Touro school opening. Touro had 20-odd campuses in the United States as well as schools in Israel, France, Rome and assorted places frequented by globetrotters.

Taking the elevator up to his office I was caught in a cloud of students, mostly Jewish, speaking a cornucopia of languages. I recognized Russian, Hebrew and Spanish among them. Youthful electricity was in the air: young people starting out in life, the energy of a motor revving, missions about to begin.

I went up to the fifth floor and was shown to Dr. Lander’s “office,” a small conference room badly in need of a paint job. The first thing that struck me was his diminutive size. I was expecting a monster of a man, a powerhouse. The man who stood there was almost tiny. And ancient. He was 90 at the time, and substantially blind, too. I had a sinking feeling in my stomach. I had expectantly taken off valuable times from other meetings to meet a very accomplished person and was not in the mood to meet a past-his-prime nonagenarian figurehead.

I went up to the fifth floor and was shown to Dr. Lander’s “office,” a small conference room badly in need of a paint job. The first thing that struck me was his diminutive size. I was expecting a monster of a man, a powerhouse. The man who stood there was almost tiny. And ancient. He was 90 at the time, and substantially blind, too. I had a sinking feeling in my stomach. I had expectantly taken off valuable times from other meetings to meet a very accomplished person and was not in the mood to meet a past-his-prime nonagenarian figurehead.

He had a warm smile on his face. “Welcome to Touro. Sit down. I have a lot to talk to you about.” There were numerous phones in front of him. An assortment of secretaries, deans and other university personnel were walking in and out of the room. He began to talk to me about some real estate issue Touro was dealing with and needed some help. Every two minutes or so we were interrupted with an urgent request; he answered each decisively and with a smile. The phones rang alternately. “Rose, hold my calls!” he yelled to his septuagenarian secretary. We talked for a few more minutes. “Senator Torricelli is on the phone,” Rose yelled. “He says it’s important.”

Dr. Lander picked up the phone and began chatting about some collegiate issue. He hung up the phone. “Let me talk to you about Touro’s mission,” he said.

Dr. Lander picked up the phone and began chatting about some collegiate issue. He hung up the phone. “Let me talk to you about Touro’s mission,” he said.

He had started Touro at the age of 54 to combat “a crisis area in Jewish survival,” he said. There are over 700 Christian colleges in the USA. Catholics alone had sponsored 311 institutions including 65 accredited colleges in New York State alone. Orthodox Jews, by contrast, had just one option: Yeshiva University. Yeshiva rejected two out of three applicants for lack of space, funding and assorted other reasons. The incidence of assimilation of Jewish youth who attended secular college was staggering.

Dr. Lander blamed complacency on the part of parents who believed that children brought up with Jewish beliefs would retain their values in college as well.

Peer pressure in secular or Christian schools cause the majority of Jewish youths to come away with the ground under them shaken and their values impaired for life.

“I disagree,” he said. “The younger years are critical to developing psychological structure.” However, the college years play a decisive role in self-identity and the formation of life values -- the overall perspective from which one sees and interprets the world. Peer pressure in secular or Christian schools cause the majority of Jewish youths who enter these institutions to come away with the ground under them shaken and their values impaired for life. Touro was to be the alternative for Jewish youth.

My head had begun to throb from the controlled pandemonium. Dr. Lander looked at me conspiratorially, and said, “Let me tell you about my 10-year plan.”

As Jews we eat matzah on Passover. Rabbi Soloveitchik explained it as follows. Risen dough, fully-baked bread, represents man in his fullness. This is the mature man: Proud of what he has achieved, set in his path, complacent with who he is; satiated and complete.

But dough begins unrisen, in a state of endless possibility. A person in his youth represents the endless possibility of mankind. Unrisen dough represents youth. Irony of ironies! We, the most ancient of people, primogenitor to the great religions, hold in our ancient hands a piece of matzah, symbolizing, in our antiquity, that the Jew is spry and youthful. He has not lost his creativity, his spirit. Age is meaningless to the Jewish people. It merely becomes a resource, a library of ideas, a reservoir of culture, a deep storehouse into which we can continually reach for ideas and providence. I looked at ancient Dr. Lander, and I saw before me a man holding a matzo: An 18-year-old boy with a twinkle lurking behind the fa?ade of a 90-year-old man.

A year or so later Dr. Lander asked me to come up to his offices again. While we were talking a woman came into the office. She had previously been a member of the faculty but had resigned to fight cancer. “How are you doing?” He stood up and spoke to her in a loving and effusive manner; they spoke for several minutes.

A year or so later Dr. Lander asked me to come up to his offices again. While we were talking a woman came into the office. She had previously been a member of the faculty but had resigned to fight cancer. “How are you doing?” He stood up and spoke to her in a loving and effusive manner; they spoke for several minutes.

“Dr. Lander, I know you’ve been carrying my insurance for the last year. Can you please keep paying for my medical?” she importuned. “I can’t afford to lose it.”

“Of course we’ll keep it, as long as you need it,” he said.

“Dr. Lander,” the woman began to weep, “I’m so scared. I still have a daughter to marry off…” The woman was shaking.

Dr. Lander said to her, “We must have faith. God in heaven is merciful. Many times in the past I thought that for Touro the end was near; but with faith, we persevered.”

He began telling her about miracles he’d witnessed.

“When I began the school it was against all odds,” he said. “All I had was a dream. Over a period of three years I was approved by New York State to open a college. It was against all odds. We had no funds. I had no Board of Trustees. I painstakingly put together a wonderful Board of Trustees. New York State Attorney General Louis Lefkowitz was on it. United States Senator Jacob Javits, State Comptroller Arthur Levitt, Mayor Abraham Beame, were some of the members on the board. This board was going to be my entryway to allow me to create what had been my dream, a Jewish college. The chairman of the board, a gentleman by the name of Eugene Hollander, a person with business acumen and leadership qualities who was also an extremely wealthy man, who had made his money in the nursing home industry.

"On September 6, 1974, three years after I founded the school and we were beginning to gain momentum, I woke up and saw a front-page New York Times article about Medicaid fraud and patient neglect in New York City’s nursing home industry. The New York Times penned over 200 articles over the course of two years. The nursing home scandal received prominent placement on newspaper front pages and nightly television newscasts for months and led to a criminal indictment of 200 nursing home owners for stealing millions of dollars. Eugene Hollander was the president of the Metropolitan Nursing Home Association, and he appeared prominently. 60 New York Times articles mentioned Eugene Hollander between September 1974 and December 1975, and his association with Touro College was mentioned in 17 of those articles. I have no idea why [the Times] repeatedly mentioned Touro, but [they] made Touro a legitimate target.

"Going well beyond normal journalistic practice, the New York Times phoned the vast majority of Touro’s trustees and asked them how they felt about sitting on the same board as Eugene Hollander. Chaos ensued. All the politicians resigned rapidly. Jacob Javits, many of the trustees, the state attorney general, Abraham Beame, disappeared like the clouds in the sky when blown away by a strong wind.

"Eugene Hollander resigned as well. I had spent the last four years building something that evaporated in front of my eyes. It would take me over five years to recover from this. During that year of the nursing home scandal, the entire school’s survival was at stake. But I had faith, and God helped, and look where we are today.”

“Forward,” he said. “We must march forward.

He continued telling stories where faith in God and persistence had guided him through. The woman listened quietly and then she sobbed, “I have faith, I just am fearful for my daughter.” Dr. Lander began crying too. I sat there as they wept quietly together.

The last time I saw Dr. Lander was four weeks ago at Cornell Hospital. He lay in bed hooked up to an assortment of machines. Touro was about to have a board call to decide on a new undertaking, a new medical school. He insisted on chairing the call from his hospital room. His daughter Hannah and longtime aide Dr. Fishman helped him out of bed and sat him in a chair.

The call lasted for around an hour. The entire board was on the call vigorously debating the pros and cons of proceeding with the new school. Before it came to a vote Dr. Lander raised his hand to signal to have his oxygen mask lifted. He wanted to say something. He leaned forward into the speakerphone. “Forward,” he said. “We must march forward. Onward. Forever onward.”

This article originally appeared in the Jewish Star.