Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

11 min read

The philosophy and inspiration behind the blessings.

Welcome to this course on the laws of brachot (blessings). Our primary focus will be the rules of reciting brachot over food – both before and after eating. Later in the course, we will discuss other types of blessings said during the course of a day – when smelling fragrances, upon observing natural phenomena, and in other situations.

Before we get into the particulars, however, some background is in order. Understanding the meaning and significance of brachot is essential to fulfilling their purpose.1 So we will dedicate this first class to an overview of what brachot are all about.

On the most basic level, a bracha is a means of recognizing the good that God has given to us. As the Talmud2 states, the entire world belongs to God, Who created everything, and partaking in His creation without consent would be tantamount to stealing. When we acknowledge that our food comes from God – i.e. we say a bracha – God grants us permission to partake in the world's pleasures. This fulfills the purpose of existence: To recognize God and come close to Him.

Once we have been satiated, we again bless God, expressing our appreciation for what He has given us.3

So, first and foremost, a bracha is a "please" and a "thank you" to the Creator for the sustenance and pleasure He has bestowed upon us.

The Midrash4 relates that Abraham's tent was pitched in the middle of an intercity highway, and open on all four sides so that any traveler was welcome to a royal feast. Inevitably, at the end of the meal, the grateful guests would want to thank Abraham. "It's not me who you should be thanking," Abraham replied. "God provides our food, and sustains us moment by moment. To Him we should give thanks!" Those who balked at the idea of thanking God were offered an alternative: Pay full price for the meal. Considering the high price for a fabulous meal in the desert, Abraham succeeded in inspiring even the skeptics to "give God a try."

Yet the essence of a bracha goes beyond mere manners. This is evident from the text of the bracha itself. Every bracha begins with the phrase "Baruch Ata Ado-noy" – "Blessed are You, God." This expresses our will that God should be blessed.

Many commentators, however, take issue with this translation, because of its implicit philosophical difficulty. How can man bestow blessing upon God, Who is lacking nothing, Who created all existence, and has infinite ability and power?! What could God possibly need from man, a mere creation?5

These commentators therefore explain "Baruch Ata Ado-noy" as a statement of recognition: "You, God, are the Source of all blessing."6 In this way, a bracha serves as a humbling reminder that it is not our "own strength that brought this prosperity" (Deut. 8:17). Rather, we express our dependence on God, acknowledging that He is the source from which our good has come.7

This concept is reflected in the word bracha which shares a root with the word berech, meaning "knee."8 In reciting a bracha, we "bend our knees" to God, so to speak, bowing in recognition of our need for, and in our appreciation of, His kindness.

Another word that shares a common root with bracha is breicha, which means "wellspring."9

Another word that shares a common root with bracha is breicha, which means "wellspring."9

This alludes to the fact that reciting a bracha opens a wellspring of blessing that flows down from the heavens. This theme is hinted in the root letters of the word "bracha" – bet, reish, chaf – whose numerical values are 2, 20 and 200. While the number one signifies the minimal amount of anything, two begins the series of multiplicity. The word bracha is made up of all the "two's," hinting to the power of a bracha to bring additional good into the world.10

There is an interesting halacha that one should have bread on the table when reciting Birkat Hamazon (Grace After Meals).11 One reason given for this is that God's blessing always manifests itself on something that already exists; if there would be no bread on the table, there would be no "receptacle" for God's blessing.12 So we see that even as we are reciting a bracha, we are simultaneously receiving God's blessing of increased prosperity. A bracha, therefore, is a key to open the flow of God's blessing into the world.13

In this regard, one who neglects to say a bracha is considered as having stolen not only from God, but also from the Jewish people,14 and ultimately all of humanity, having denied them an opportunity to receive God's blessing.

The two concepts that we have discussed so far – recognizing God's kindness and bringing blessing into the world – are inter-related. Let's explore this connection a bit deeper:

When God created the world, He put everything in place before creating man. The sun and the moon, fowl and fish, animals and insects, and every living creature were all created before man. When Adam would finally arrive on the scene, he was to find a "set table" before him – a magnificent, finished world. But the Torah tells us there was one thing that God saved for man to complete.

"Now all the trees of the field were not yet on the earth, and all the herb of the field had not yet sprouted, for God had not sent rain upon the earth, and there was no man to work the soil." (Genesis 2:5)

The plant-life would have to wait, concealed under the surface of the ground, until the first rainfall. And why had it not rained? Because, the Midrash says, God wanted man to turn to Him and pray for rain. That way, when the rain fell, man would appreciate each and every drop as God's gift to the world.15

God created the world with the purpose of bringing man close to Him. So He created a system which requires the spiritual efforts of man. When we say a bracha, it is our recognition that we need God, and are indeed utterly dependent upon Him. This forges a meaningful relationship with God, brings us closer to Him – and opens up the gates of blessing.16

So it is the "Baruch Ata" – recognizing God as the source of blessing – that opens the "breicha," the wellspring of abundance, and completes the partnership between man and God that sustains the world.

We can now understand how some commentators explain the simple translation of the phrase Baruch Ata as "Blessed are You." Of course, everyone agrees that God does not need our blessing. However, in a sense it is man's job to prompt God, so to speak, to act with kindness and bring blessing into the world. "Baruch Ata Ado-noy – may You, God, allow Yourself to exercise Your power of goodness toward mankind."17

Understanding the meaning behind these blessings and the power they possess can transform the mundane act of eating into a deeply spiritual experience. Before biting into an apple, we thank God for making the apple, thus making the physical act of eating into a holy act. And in doing so, we elevate ourselves from the level of "animal behavior" to the unique and lofty level of "human being."18

The Torah says: Man does not live by bread alone, but rather on the word of God.19 The kabbalists cite this verse to show that food is more than just nourishment for the body. There are also "sparks of holiness" contained in food, and when we eat that food in an appropriate way (i.e. kosher food, and saying a bracha), the holiness in that food is unlocked and nourishes the soul. This is crucial to our overall health, because "Man does not live by bread alone."20

Just as food helps the soul connect to the body (because without food, eventually the soul will separate from the body), brachot connect the soul to the Infinite. The kabbalists explain that the mouth is where the soul fuses with the body, which is why food goes in there and why brachot are spoken there – as they maintain the soul's connection to the Infinite.21

The material world presents us with two choices: to enjoy it as a gourmet (spiritually) or as a glutton (materially). To enjoy it only in itself, or to use the aesthetic experience to leap toward transcendental awareness. The bracha is a user-friendly method for elevating the aesthetic experience into the wow! that every moment of life can and should be.22

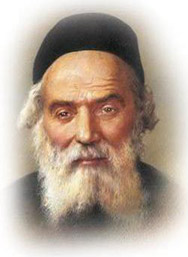

Maimonides codifies the laws of brachot with the mitzvot that bring one to love of God. Every blessing expresses our yearning to connect with God. A true story is told that illustrates this idea:

"One time, a chassidic rebbe, Rabbi Aaron from Karlin, took an apple in his hand, and his student took an apple as well. Each of the men said a bracha and began to eat. When they were finished, the rebbe said to his student:

"One time, a chassidic rebbe, Rabbi Aaron from Karlin, took an apple in his hand, and his student took an apple as well. Each of the men said a bracha and began to eat. When they were finished, the rebbe said to his student:

"Do you know the difference between you and me? You were hungry and wanted to eat an apple. But to do so, you first needed to say a bracha. In my case, I looked around at the beauty of our world and desperately wanted to call out in praise of God. Since our Sages made brachot the context to praise God, I needed to take an apple. In other words, you said a bracha to eat the apple, and I ate the apple to say a bracha!"23

Sefer Olat Tamid lists 13 verses that one fulfills each time one says a bracha properly. Included among them:

To review, a bracha:

This course is intended to provide halachic principles and examples. There are many nuances to Jewish law, and in actual practice one should consult with a local rabbi.

This course follows these main source materials:

For those who wish to reference more primary sources, we provide footnotes throughout our lessons:

We will also refer extensively to rulings by these contemporary Sages: